Urbanisation at the Margins

How are the peripheral settlements of Kashmiri and Kandahari evolving, and what does this tell us about the power to shape the urban?

Authors:

Eleonora Balestra

Hamdat Fathi Mahmud

Fatma Sayyid Athman

Joëlle Martz

By adopting a historical lens, our research traced the stories and memories of those who have built and inhabited Kashmiri and Kandahari over decades of its incremental yet continuous urbanisation.

These stories revealed the many ways in which residents navigate fragmented land tenure, engage in tacit negotiations with neighbours, and cope with the ambiguous status of their neighbourhoods within the frameworks of urban governance that are currently gaining relevance and capacity in Lamu.

![]()

Eleonora Balestra

Hamdat Fathi Mahmud

Fatma Sayyid Athman

Joëlle Martz

By adopting a historical lens, our research traced the stories and memories of those who have built and inhabited Kashmiri and Kandahari over decades of its incremental yet continuous urbanisation.

These stories revealed the many ways in which residents navigate fragmented land tenure, engage in tacit negotiations with neighbours, and cope with the ambiguous status of their neighbourhoods within the frameworks of urban governance that are currently gaining relevance and capacity in Lamu.

“Some would term what is happening in these settlements as classical urban sprawl. There isn’t much order; the only authority present at that time were the original land owners, who allowed the people to settle there. The way they build is very different to the old town [...] these are the houses of their own dreams.”

- Resident of Lamu Town

affiliated with the

National Museum of Kenya

Constant tacit or explicit negotiations characterise informal urbanisation in Kashmiri and Kandahari, which stands in sharp contrast to the municipality’s practice of marking new structures that don’t fit regulatory norms with a bright red ‘X’. These visual markers point to tensions that result from growing enforcement capacities of rigid laws, recently published land-use plans, and broader development projects that mismatch more incremental, negotiated ways of urbanising.affiliated with the

National Museum of Kenya

Urbanisation in these settlements is shaped by both necessity and hope for future recognition.

Projects

Urbanisation at the Margins #2501

Between Formal Plans and Everyday Life

On my daily walks through the narrow streets of Kashmiri and Kandahari, I developed a little guessing game. Whenever I came across new red markings on bare, unplastered walls, I would try to guess what might have led the municipal surveyors to judge a particular building as failing regulations. Most of the time, I had barely a clue. But what grew from these regular observations of red X’s along my routes was a much more pressing question:

How do the residents here, the people I had come to think of as neighbours, respond to the growing presence of local urban authorities? And how does this shape the production of urban space, which until now had been almost entirely in the hands of those who call this place home?

![]()

To this day, Kashmiri and Kandahari are shaped by self-building practices, but formal rules are starting to have a greater influence as the local government becomes larger and more effective in enforcing them. This research looks at how urban spaces are being shaped through the ongoing interaction between everyday building practices and official regulations.

How do the residents here, the people I had come to think of as neighbours, respond to the growing presence of local urban authorities? And how does this shape the production of urban space, which until now had been almost entirely in the hands of those who call this place home?

To this day, Kashmiri and Kandahari are shaped by self-building practices, but formal rules are starting to have a greater influence as the local government becomes larger and more effective in enforcing them. This research looks at how urban spaces are being shaped through the ongoing interaction between everyday building practices and official regulations.

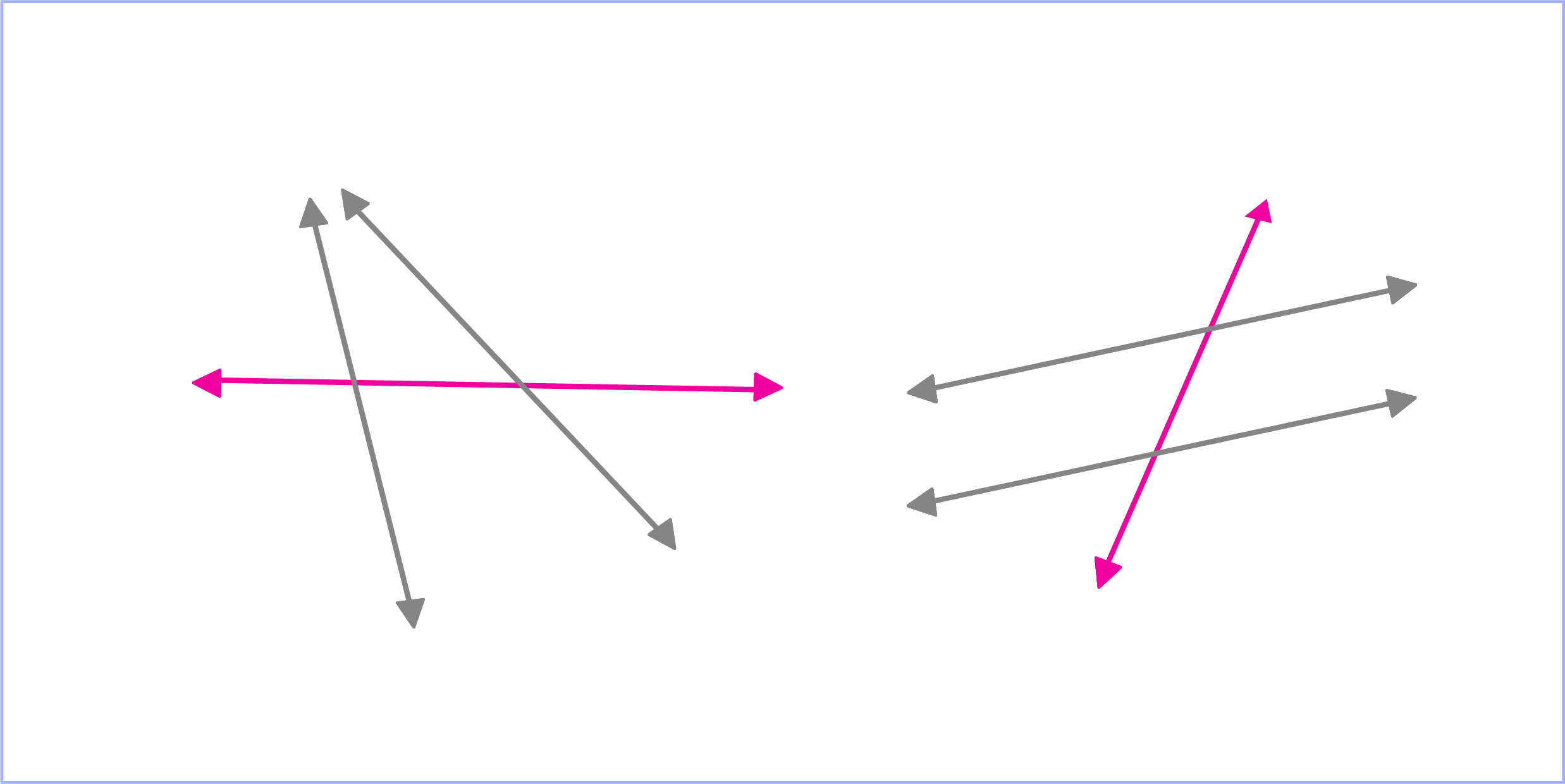

In Kashmiri and Kandahari, it is common for people to build their own houses, either by constructing them themselves or hiring professionals. Hardly a day passes without the sounds of construction nearby or the sight of donkeys carrying sand or building blocks through the streets. Prominent urban anthropologist Teresa P.R. Caldeira has described what is happening here as “peripheral urbanisation.” She theorises it as more than just development at the physical edges of a city; rather, it is a mode of producing urban space that is driven by the agency of residents themselves. Tied to financial means and personal opportunities, this process is typically incremental and interacts with formal markets and governance systems in ways that cross and connect these seemingly separate spheres. Such relationships are often described as transversal.

“transversal” is something that moves sideways and thus crosses boundaries — between formal and informal, powerful and less powerful, official and unofficial worlds.

Re-Engaging Informality

To explore and describe the interactions between residents and local government, I chose to use the terms formal and informal — a distinction that many influential scholars have criticised for decades. Building on these critiques, this study takes a closer look at the complexities of informal spaces.

The disenfranchised express a deep desire to live an informal life, to run their own affairs without involving the authorities or other modern formal institutions” (Bayat 1997, 53)

The disenfranchised express a deep desire to live an informal life, to run their own affairs without involving the authorities or other modern formal institutions” (Bayat 1997, 53)

It is important not to think of informality only as the opposite of official, state-defined rules, as it is more than the absence of such. It is an alternative form of social organisation. Flexibility, adaptability, and openness to negotiation may support people who are commonly excluded from formal systems. Though often connected to poverty, informality isn’t limited to people with low incomes. Middle-class people, too, increasingly live, work, and invest in informal spaces.

Everyone can engage with informality; some have the privilege to do so quietly, while others carry that label openly on their shoulders.

Everyone can engage with informality; some have the privilege to do so quietly, while others carry that label openly on their shoulders.

Tracing the In-Betweens

The foundations of urban life in Kashmiri and Kandahari are built on informally subdivided land, where former shambas (Kiswahili for agricultural land) were split and sold by their owners. As urbanisation gradually built over the small path that once separated these plots, the municipal garbage truck, which used to pass through to reach the town’s main dumping site behind Kandahari, was forced to find new routes. Over time, a new path, commonly referred to as TakaTaka road (TakaTaka is a Kiswahili term for garbage), emerged there, where unequal opportunities to build left plots empty.

Today, the municipality relies on this informally developed infrastructure, but it is mainly the residents who actively defend it. When someone attempts to lay a foundation for a new house on this road, others tend to whistleblow immediately. As a result, state enforcement is typically quick to show up at the construction site to intervene and halt construction attempts within hours.

The case of the TakaTaka road shows how the formal system sometimes works with informal structures to help achieve its own goals, while people involved in informal activities may use formal rules to advance their interests.

The way the TakaTaka road emerged is a good example of ‘mutual accommodation’ — a term used by urban scholar Carole Rakodi to describe how formal and informal actors work together to get access to land in African cities. My research shows that this idea also helps explain what’s happening in Kashmiri and Kandahari today.

As formal and informal actors adjust to one another, they sometimes, whether intentionally or not, help to legitimise each other’s actions. This is how mutual accommodation takes shape.

The case of the TakaTaka road shows how the formal system sometimes works with informal structures to help achieve its own goals, while people involved in informal activities may use formal rules to advance their interests.

The way the TakaTaka road emerged is a good example of ‘mutual accommodation’ — a term used by urban scholar Carole Rakodi to describe how formal and informal actors work together to get access to land in African cities. My research shows that this idea also helps explain what’s happening in Kashmiri and Kandahari today.

As formal and informal actors adjust to one another, they sometimes, whether intentionally or not, help to legitimise each other’s actions. This is how mutual accommodation takes shape.

Listening to Urban Rhythms

The people of Kashmiri and Kandahari have been shaping their neighbourhoods through mutual accommodation long before state institutions became involved in these areas. This study found that their incremental ways of building — a new wall here, a small extension there — make it easier for neighbours to adjust to one another over time. These slow, flexible timelines, shaped by gradual, adaptive, and sometimes opportunistic actions, allow people to create their own forms of acceptance and legitimacy, outside any formal rules or laws.

In contrast, formal planning tends to arrive with strict, project-based timelines and fixed ideas about what should happen and when. These big projects rarely leave room for the kinds of everyday negotiations that allow residents to quietly accommodate one another. Without this slow process of adjustment, formal interventions can easily feel disruptive, even threatening, and often struggle to gain acceptance within the community.

The frictions and accommodations evident today will shape the evolving relationship between state authority and resident agency in the future, as planning efforts continue to permeate the informal urban fabric of Kashmiri and Kandahari.

The frictions and accommodations evident today will shape the evolving relationship between state authority and resident agency in the future, as planning efforts continue to permeate the informal urban fabric of Kashmiri and Kandahari.