Maritime mobilities

How does the construction of the new port disrupt maritime mobility patterns and marine-based livelihoods? What interventions will be needed to safeguard these for the future, and which new livelihoods might emerge?

The new regime of mobility which the LAPSSET project aims to establish disrupts existing maritime livelihoods and mobility across the Lamu region. Sustained civil society action has resulted in a one-time, highly contested compensation scheme for fisherfolk. But many in the community are aware that this compensation does little to guarantee locals’ inclusion in economic development, nor mitigate the risks and threats to existing way of life.

Meanwhile, anxiety about the future of Lamu is prompted by rumours about a new bridge and ferry connections and fears about the closure of the dug-out channel that facilitates crucial east-west travel in the archipelago.

Meanwhile, anxiety about the future of Lamu is prompted by rumours about a new bridge and ferry connections and fears about the closure of the dug-out channel that facilitates crucial east-west travel in the archipelago.

Through ethnography and mapping, our work explores the relationships between the ways people move across the archipelago and their ability to sustain themselves. It shows how mangrove, fishing, and tourist livelihoods depend on maritime movement, shaped by the intricacies of tides, seasons, and state security. Following diverse narratives from different groups of people, the research addresses the tension between hopes for a prosperous future and fears of losing livelihoods.

Projects

Maritime mobilities #2304

A Port of Splintered Promise

“These people”

We arrive in the early hours of dawn and dock at the main jetty of Mokowe, Lamu County’s first mainland town west of the archipelago. From Lamu town, the commute takes a mere 15 minutes, and one does not have to wait long for the boat to garner the dozen or so passengers it needs to make the journey worth the captain’s while. Traffic commences early on this most frequented of thoroughfares, as the movement of cargo, schoolchildren, and government functionaries underlies the island’s dependence on mainland supplies and infrastructure.

Morning cargo on the shore of Mokowe Jetty

One is greeted by heaps of cargo littered about the place, waiting to be loaded onto cargo boats embarking back towards various stations within the Island network. A procession of porters animates the scene, transferring merchandise between lorries and cargo ships. On-land conveyance awaits further on from the slope of the shore, with vans and buses idling alongside private-hire estate cars and motorbikes.

Porters at Mokowe

A porter frantically waves at us from afar, taking exception to our filming of the spectacle. The man walks up to interrogate our objectification of their drudgery and is unusually verbose for his occupation, asking if we thought they were “imbeciles”. Courtesy obliged us to concede to his protests all too willingly, but the man seemed to relish this break from his labour and continued conversing in practiced English.

We talked of his occupational hazards, and he went through a litany of accidents they had grown accustomed to, including overloading, capsizing, and even fires. Soon this turned towards what the future held, which gave us a segue to mention the prospect of a rumoured bridge between Lamu town and the mainland. This was seen as part of the infrastructural upgradation that LAPSSET brought to the region, and would streamline the daily commute of many.

We arrive in the early hours of dawn and dock at the main jetty of Mokowe, Lamu County’s first mainland town west of the archipelago. From Lamu town, the commute takes a mere 15 minutes, and one does not have to wait long for the boat to garner the dozen or so passengers it needs to make the journey worth the captain’s while. Traffic commences early on this most frequented of thoroughfares, as the movement of cargo, schoolchildren, and government functionaries underlies the island’s dependence on mainland supplies and infrastructure.

Morning cargo on the shore of Mokowe Jetty

One is greeted by heaps of cargo littered about the place, waiting to be loaded onto cargo boats embarking back towards various stations within the Island network. A procession of porters animates the scene, transferring merchandise between lorries and cargo ships. On-land conveyance awaits further on from the slope of the shore, with vans and buses idling alongside private-hire estate cars and motorbikes.

Porters at Mokowe

A porter frantically waves at us from afar, taking exception to our filming of the spectacle. The man walks up to interrogate our objectification of their drudgery and is unusually verbose for his occupation, asking if we thought they were “imbeciles”. Courtesy obliged us to concede to his protests all too willingly, but the man seemed to relish this break from his labour and continued conversing in practiced English.

We talked of his occupational hazards, and he went through a litany of accidents they had grown accustomed to, including overloading, capsizing, and even fires. Soon this turned towards what the future held, which gave us a segue to mention the prospect of a rumoured bridge between Lamu town and the mainland. This was seen as part of the infrastructural upgradation that LAPSSET brought to the region, and would streamline the daily commute of many.

However, this proposition was met with a patient sigh, followed by a rather resigned explanation of why this prospect, real as it was, could not materialise. A plan for the bridge was indeed proposed, but the local boatsmen vehemently protested against such inconsiderate benevolence, seeing as a land connection would spell an end to their means of livelihood. Excluding himself as a Kikuyu mainlander, he decried the siege mentality of the islanders:

“They feel like the main government is working with the Chinese, and the Swahili people are kind of just pushed aside. I remember the Chinese proposed to construct the bridge very well – they even came with a map… but these Swahili from Lamu refused it. The main reason is that the bridge would deny them jobs.”

“These people… they don’t like change, they don’t like development, they want the same of what they have – that is why they are against such projects.”

This political rift, mapped onto ethnic difference, has been central to Lamu’s relationship with the national government.

Coastal communities tend to look back on the Omani maritime empire as a period of prosperity for Lamu, in contrast to the marginalization of the region since Kenyan independence. Kikuyu communities arguably bore the brunt of colonial oppression during British rule, and their anti-colonial resistance is foundational to Kenyan independence and post-independence nation-building. However, Kikuyu political elites, with president Jomo Kenyatta at the top, are also widely described as the biggest landgrabbers of Kenya, responsible for the country’s neo-colonial injustices after independence.

Mirroring the feelings of marginalisation the porter felt in Bajuni-led Lamu, this complex history inhabits contemporary politics and social dynamics. Coastal communities are wary of state impositions from Kikuyu and other “upcountry Kenyan functionaries, of local real-estate speculation by their investment-savvy middle class, and of the mainland’s vague but consequential conflation of Al-Shabaab with the local community.

The porter occupied us for a rather generous half hour, before we realised he was holding out for some renumeration for his time. This made us realise how little of his exposition depended on our prompts, and why it had all seemed rather rehearsed. Well-meaning wazungu were to be sold a story, or so it seemed.

Infrastructure as a frame of analysis

While the LAPSSET infrastructure project served as both topic and context in our research, we were also inspired to mobilize infrastructure as an analytical lens. By virtue of the vastness of its purview, and the indeterminacy of the boundaries of its causal and effectual spheres of influence, infrastructure evades disciplinary caging. It does however lend itself quite naturally as a site of inquiry to a diversity of social science disciplines such as anthropology, history, human geography, urban studies, and science and technology studies. Each of these offer approaches that addresss particular aspects of such a boundless chain of phenomena.

In short, the challenge confronted by a researcher is first and foremost of delimitation; a matter of honing in on a case through a selection of methods, and then framing it within spatial, social, and temporal constraints.

Ethnographic imprecision

In order to grapple with the effects of the LAPSSET project spread across such a spatially dispersed area - and to accommodate the nebulous phase this inquiry finds itself in - this undertaking calls for a lenient imprecision in its ethnographic approach. The aim here is to document social attitudes, responses and expectations around the construction of the port.

As Hannah Knox and Penny Harvey summarised the challenge of such a premise, “when studying infrastructure the anthropologist must confront the problem of locating an ethnographic site without limiting the scale of description.”

As Hannah Knox and Penny Harvey summarised the challenge of such a premise, “when studying infrastructure the anthropologist must confront the problem of locating an ethnographic site without limiting the scale of description.”

Following suit, this study aims to take account of the variety and instability of human relations in the shift brought about by this infrastructural intervention within the community, and attempts to offer a snapshot of the social and cultural dynamics of change brought about by the port.

Imaginaries of development

To envisage infrastructure within a public imaginary is to dwell on an aesthetic plane of conception. Framing infrastructure as such relegates its technical function to a separate, secondary concern; the priority instead being the imaginative potential of its image. This implies not only the visuality of the spectacle itself, but also the sense in which it is internalised by its addressees.

Brian Larkin offers a masterful exposition of this potential, pushing back against the trope of ‘infra’ as denoting something hidden and behind the scenes. To be fair, the notion of an out-of-sight network of processes, one that enables the end-user a certain convenience through an unassuming interface, does provide an inexhaustible avenue of research. But Larkin argues that there is no end to the relational webs that one may consider in trying to come to grips with infrastructure, and emphatically states that “discussing infrastructure is a categorical act… a moment of tearing into those heterogeneous networks to define which aspect of which network is to be discussed.”

Drawing license from the clarity of Larkin's declaration, this inquiry’s categorical concern is the connotative baggage of new Lamu port within the local community. Though having enjoyed centuries of prominence as a thriving port city in past regimes, there is a palpable sense of modernity’s belated arrival that the new port announces in the current, Kenyan iteration of Lamu. A “game-changer” as it is so tritely brandished in official pronouncements, the port is held up as Lamu’s fast track ticket to development.

Such proclamations by government officials imply a tacit admission of feeling left behind so far, and speak of a motivating disjunction sorely felt between Lamu’s as-is, and its desired to-be. The trope of the port as a game-changer therefore is not without conviction, and is emblematic of the “postcolonial state’s imaginative investment in technology,” dissonant as it might be with the heritage-tinged, donkey-cart romance of Lamu’s Old Town.

“As a regional gateway to the riches of East Africa, Lamu has the chance to shed its image of a developmental hinterland for a new prominence on the international stage. The proposed LAPSSET project will immensely contribute to the opening up of the County externally to other Port Cities and Nations of the world.”

Such proclamations by government officials imply a tacit admission of feeling left behind so far, and speak of a motivating disjunction sorely felt between Lamu’s as-is, and its desired to-be. The trope of the port as a game-changer therefore is not without conviction, and is emblematic of the “postcolonial state’s imaginative investment in technology,” dissonant as it might be with the heritage-tinged, donkey-cart romance of Lamu’s Old Town.

Maritime mobilities #2303

The role of maritime mobility in sustaining livelihoods within the Lamu Archipelago

Tides of Change

The role of maritime mobility in sustaining livelihoods within the Lamu Archipelago

Lamu archipelago, 2023

Tanja Meier

Download PDF

Tanja Meier

Download PDF

"The place they chose to build LAPSSET port is dangerous. Because if the Mkanda channel is closed, Lamu will be finished."

This is how Mohammad Mbwana - Shungwaya Welfare Association chairman and a local historian - expressed his fear for Lamu's future in our interview. According to Mbwana, disruptions to maritime mobility will be the end of Lamu. The infrastructural development in Lamu is anticipated with both a sense of promise and violence. The government promises growth, modernity, and prosperity for the region against a background of dispossession, displacement, and exclusion.

Lamu County is the northernmost county on the Kenyan coast. It borders Somalia and has direct access to the Indian Ocean. The locals do not perceive this ocean as a border but rather as an extension of the land and life around the islands. Many indigenous communities inhabit the Lamu archipelago. Their cultural identity depends on the natural resources surrounding the archipelago.

Water is of paramount importance, serving as a base for both the fishing industry and mangrove management, two primary means of livelihood within the island network. The sea is often overseen as an environment where people navigate and manoeuvre. However, maritime societies constantly interact between land and sea, and these connections shape their knowledge and practices. Simultaneously, littoral communities, such as the inhabitants of Lamu, are connected to their hinterlands socially, politically, and economically.

LAPSSET may create new markets for Kenya and the region through which state income can be generated. However, these ambitions turn into infrastructural violence around Lamu port, with severe ramifications for various social groups in the wider region.

LAPSSET may create new markets for Kenya and the region through which state income can be generated. However, these ambitions turn into infrastructural violence around Lamu port, with severe ramifications for various social groups in the wider region.

Honing in on transport

Literature on LAPSSET has focused on the social upheaval accompanying infrastructure, touching upon events of land grabbing, fishing bans, monetary compensations, and other processes that animate analysis on a more local scale.

However, within the broad purview of analysing such a massive international project, the disruption of regional maritime mobility has thus far evaded scholarly analysis.

Given a considerable part of the archipelago experience is commuting by boat, we saw this as an opening to inquire further on a topic that suited the limitations of our fieldwork. We thus honed in on maritime mobility and began by questioning the numerous claims on Lamu’s waterways.

How is Lamu’s maritime mobility disrupted by the ongoing port development?

What effects does this have on livelihoods and the movement within the Lamu Archipelago?

What alternatives, promises, and opportunities emerge to safeguard the future of Lamu’s current livelihoods?

Building up to Mkanda

Mkanda is a channel that connects Lamu East with Lamu West. It drastically shortens the commute between islands and provides a calm, secure alternative to the outer seas. The canal cuts through the mangroves between the mainland and Manda Island.

In the 19th century, the maritime economy of the archipelago was dominated by British colonial rule. After independence, the Kenyan state took control of regulating trade.

“In 1978, mangrove harvesting and export to the Middle East was banned, forcing boat captains to resort to other occupations, such as being tour guides. In this and other ways, government involvment fueled the economic decline of the region.”

Before this curtailment of trade, large dhows crossed the outer sea and sailed around the Lamu Archipelago and

![]()

Satellite image of Mkanda channel and Wiyoni town on the bottom left corner

According to fishermen, the government-funded dredging of Mkanda around the year 2000 countered local economic decline and allowed small motor boats to navigate safely within the archipelago. Some people argue that the channel was dug to improve the archipelago’s security, while others interpret it as a precursor to the new port. Furthermore, the dredging allowed for land reclamation near Lamu town, giving rise to the new urban area of Wiyoni. The exact motives behind the government-funded dredging remain unclear; thus, it is hard to distinguish its objectives from both positive and negative side effects. Nonetheless, the channel’s importance to Lamu is undeniable.

The construction of Mkanda also played a role in the transformation of Pate Island. Trade across the Indian Ocean long shaped the orientation of towns such as Pate towards the ocean. However, since the monopolisation of the trans-oceanic trade, these towns were no longer beneficiaries of this trade. This new economic situation led the island to reorient itself towards the mainland side of the archipelago, where smaller boats could more easily dock.

In the 19th century, the maritime economy of the archipelago was dominated by British colonial rule. After independence, the Kenyan state took control of regulating trade.

“In 1978, mangrove harvesting and export to the Middle East was banned, forcing boat captains to resort to other occupations, such as being tour guides. In this and other ways, government involvment fueled the economic decline of the region.”

Before this curtailment of trade, large dhows crossed the outer sea and sailed around the Lamu Archipelago and

across the Indian Ocean.

The maritime economy was then gradually replaced by steamboats operating between British India and East Africa. Today, mostly small boats circulate the island - and captains keep from the outer seas too hazardous to navigate.

Satellite image of Mkanda channel and Wiyoni town on the bottom left corner

According to fishermen, the government-funded dredging of Mkanda around the year 2000 countered local economic decline and allowed small motor boats to navigate safely within the archipelago. Some people argue that the channel was dug to improve the archipelago’s security, while others interpret it as a precursor to the new port. Furthermore, the dredging allowed for land reclamation near Lamu town, giving rise to the new urban area of Wiyoni. The exact motives behind the government-funded dredging remain unclear; thus, it is hard to distinguish its objectives from both positive and negative side effects. Nonetheless, the channel’s importance to Lamu is undeniable.

The construction of Mkanda also played a role in the transformation of Pate Island. Trade across the Indian Ocean long shaped the orientation of towns such as Pate towards the ocean. However, since the monopolisation of the trans-oceanic trade, these towns were no longer beneficiaries of this trade. This new economic situation led the island to reorient itself towards the mainland side of the archipelago, where smaller boats could more easily dock.

Previously - when the island was still oriented towards the outer sea - places like Shanga and Kizingitini were the main docking places on Pate Island. Now, though, Mtangawanda is the island's main dock, easily accessible as it is through the channel from Amu and the mainland.

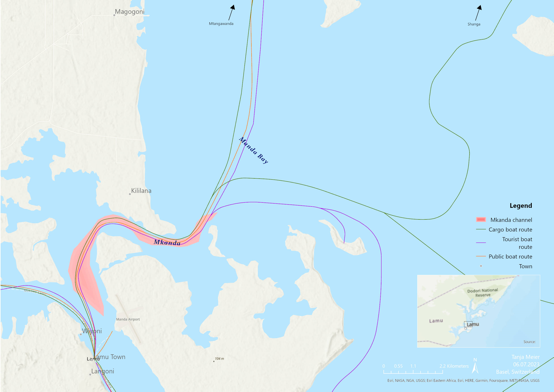

Routes going through Mkanda connecting Lamu with Pate Island (Mtangawanda & Shanga)

Today, Mkanda is a highly frequented water passage for cargo, tourists, and public transport. Using the channel to commute between Lamu East and Lamu West saves travel time and reduces fuel costs against the sea route. Moreover, Mkanda is crucial for Lamu's fishermen to operate all year round and avoid dangerous voyages into the outer sea.

"For the route of Shela (outer sea) - it is seasonal. When the sea is rough, they use the Mkanda fishing route," explains BMU Amu Chairman.

The Mkanda channel is especially important during the rainy season when the sea picks up, and the route through the outer sea becomes dangerous and impassable for small boats. "So, most of the time, when the sea picks up, we try to advise them not to cross there [the outer sea]. The channel is more on this side [inside the archipelago]. So, we try fishing within here," explains the chairman.

Lamu Port from Mkanda

Although Mkanda is at the centre of the archipelago, many other waterways are highly important. Map 5 displays some of the leading maritime routes that are used regularly. The map shows that maritime routes in the Lamu Archipelago are not only used by fisherfolk but are crucial to other activities such as mangrove cutting, cargo shipping, public transportation, and NGO projects.

Main waterways on Lamu archipelago

The Goliath of global trade

Manda Bay was chosen for the construction of the new port because of its natural geography. The deep sea level here allows several large ships to dock and manoeuvre in the port area simultaneously, which is supposed to facilitate large-scale trade.

Most aspects of the new projects are financed through public-private partnership (PPP), making negotiations complicated. Within this framework, Kenya’s government can contribute by providing land and other investments and profit from the share in (tax)-revenues. Such neo-colonial invitations are not new to the continent. Foreign investors and companies are the primary beneficiaries of the project. Officials are quick to emphasise, however, that this also offers new opportunities for the middle class:

Most aspects of the new projects are financed through public-private partnership (PPP), making negotiations complicated. Within this framework, Kenya’s government can contribute by providing land and other investments and profit from the share in (tax)-revenues. Such neo-colonial invitations are not new to the continent. Foreign investors and companies are the primary beneficiaries of the project. Officials are quick to emphasise, however, that this also offers new opportunities for the middle class:

“You know, Hindi – people have taken land for speculation. Because Hindi is where the project is, and people anticipate it. People know that Hindi will be another place like Dubai in the next 10-20 years.”

The adverse effects of the project are manifold. Environmental concerns and loss of existing livelihoods resulted in various protests and community outcries in Lamu. Coalitions such as Save Lamu understand the community’s worry about the destruction of mangroves and corals and, therefore, the threat to the environment and the livelihoods of Lamu. People are not entirely opposed to LAPSSET but disagree with its violent and exclusionary implementation, with claims of unequal distribution and benefits not being solved.

The port also raises new questions about logistics, ownership and access in Lamu. Increased security measures and the intensified flow of commodities shape transportation patterns. This overlooks local concerns and redirects the focus to a more global economy. It also reconfigures possession and blurs the boundaries of the origin of goods. Moreover, the question of locating accountability becomes more obscure.

The port also raises new questions about logistics, ownership and access in Lamu. Increased security measures and the intensified flow of commodities shape transportation patterns. This overlooks local concerns and redirects the focus to a more global economy. It also reconfigures possession and blurs the boundaries of the origin of goods. Moreover, the question of locating accountability becomes more obscure.

Expected change in maritime routes

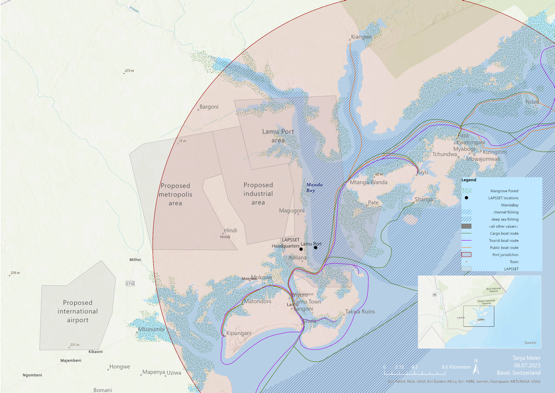

The County Integrated Development Plan 2023-2027 emphasises large-scale growth in terms of mobility on land and marine. Highways connecting Lamu to the broader region and the port connecting Lamu - and, more broadly, East Africa - to the Indian Ocean disrupts existing mobility patterns. How these patterns may change in the future is a matter of contestation today.

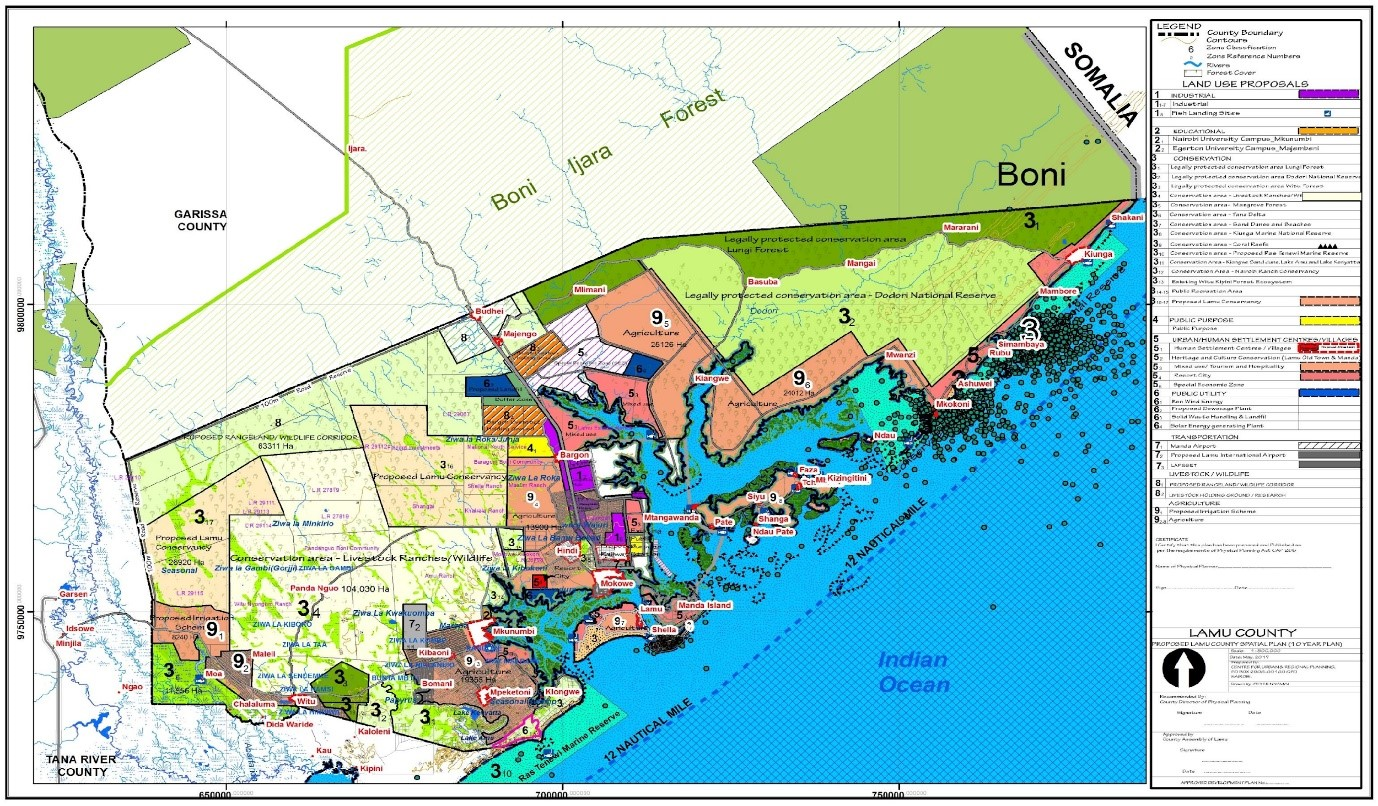

The plan identifies the provision of land for industrial development, but it does not specify future land usage. However, it does anticipate the development a spatial plan in the coming years.

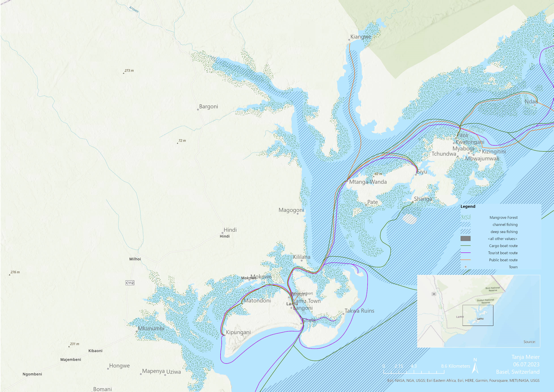

Seasons, tides, towns, and natural resources influence current mobility patterns in the Lamu archipelago. The map below shows the most frequent waterways on the archipelago and the fishing areas and mangroves around the port area.

![]()

Mobility patterns in Lamu archipelago

The map below shows the extent of Lamu Port and future development areas. These areas will shift the balance of development to the mainland and affect maritime mobility patterns.

“The establishment of the port may make the existing route via the Mkanda channel unviable. As a result of the LAPSSET implementation, these routes are therefore at the centre of anxiety about the future of the region.”

![]()

Maritime mobility patterns and LAPSSET development areas.

The plan identifies the provision of land for industrial development, but it does not specify future land usage. However, it does anticipate the development a spatial plan in the coming years.

Seasons, tides, towns, and natural resources influence current mobility patterns in the Lamu archipelago. The map below shows the most frequent waterways on the archipelago and the fishing areas and mangroves around the port area.

Mobility patterns in Lamu archipelago

The map below shows the extent of Lamu Port and future development areas. These areas will shift the balance of development to the mainland and affect maritime mobility patterns.

“The establishment of the port may make the existing route via the Mkanda channel unviable. As a result of the LAPSSET implementation, these routes are therefore at the centre of anxiety about the future of the region.”

Maritime mobility patterns and LAPSSET development areas.

The plan stress the establishment of highways, as well as new towns and commerce centres on the mainland. The focus lies on a solid road network connecting Lamu Port to other parts of Kenya, South Sudan, and Ethiopia.

![]()

County Spatial Plan (by County Government of Lamu, 2023)

Once the port is fully operational, access to existing waterways might change, and small-scale boating may face more significant restrictions, as the new port prioritises large cargo ships.

The fear of losing personal investments in small-scale livelihoods is shared among many residents. However, the shift from small-scale livelihoods that provide individual incomes to a large-scale port industry is undoubtedly expected to bring changes in the maritime mobility and the livelihoods on the Lamu archipelago.

Despite the expectations and fears, what remains unanswered is whether the promise of modernisation leaves room for small-scale maritime livelihoods in the future.

![]()

Cargo boats docking at Lamu Port

County Spatial Plan (by County Government of Lamu, 2023)

Once the port is fully operational, access to existing waterways might change, and small-scale boating may face more significant restrictions, as the new port prioritises large cargo ships.

The fear of losing personal investments in small-scale livelihoods is shared among many residents. However, the shift from small-scale livelihoods that provide individual incomes to a large-scale port industry is undoubtedly expected to bring changes in the maritime mobility and the livelihoods on the Lamu archipelago.

Despite the expectations and fears, what remains unanswered is whether the promise of modernisation leaves room for small-scale maritime livelihoods in the future.

Cargo boats docking at Lamu Port