Ecologies of Belonging

How does home-building shape people’s life stories and their sense of belonging in Lamu? What do common building materials such as coral stone and mangrove wood tell us about the future of Lamu?

Most new houses on Lamu island are built with local coral stones and mangrove wood. These ancient building materials are key to Lamu’s world-famous architectural heritage, yet home-builders often integrate them with modern techniques such as poured concrete. These building practices raise pressing questions of who belongs to Lamu.

Lamu’s coral stones come from the quarry of Maweni on nearby Manda Island. Workers in this village carve the stones by hand from the coral stone bedrock of the island. They transport the stones by boat and donkey to Lamu, where they are used to build new houses on the outskirts of the historic town. Prospects of prosperity have long attracted people to work and live in Maweni, which has been a site of coral stone extraction since at least the 1980s. Many in this community of stone workers hail from western Kenya and are considered to be outsiders to the region.

Our research focused on the relationship between Lamu and Maweni. What do they share? What separates them? And how do these communities depend on each other?

Lamu’s coral stones come from the quarry of Maweni on nearby Manda Island. Workers in this village carve the stones by hand from the coral stone bedrock of the island. They transport the stones by boat and donkey to Lamu, where they are used to build new houses on the outskirts of the historic town. Prospects of prosperity have long attracted people to work and live in Maweni, which has been a site of coral stone extraction since at least the 1980s. Many in this community of stone workers hail from western Kenya and are considered to be outsiders to the region.

Our research focused on the relationship between Lamu and Maweni. What do they share? What separates them? And how do these communities depend on each other?

Building a house out of permanent materials is a common aspiration. Yet living in Lamu and Maweni comes with very different challenges. While most inhabitants of Lamu’s neighborhoods enjoy tenure, the inhabitants of Maweni face precarity and the risk of eviction. Few of their homes are built with the precious stones around which they have organized their livelihoods. Most homes in Maweni are made out of a combination of thatch, mud, and wood. Despite these inequalities, residents’ lives in both Lamu and Maweni are interlaced with complex stories of aspiration and belonging that are not contained by either of these locations.

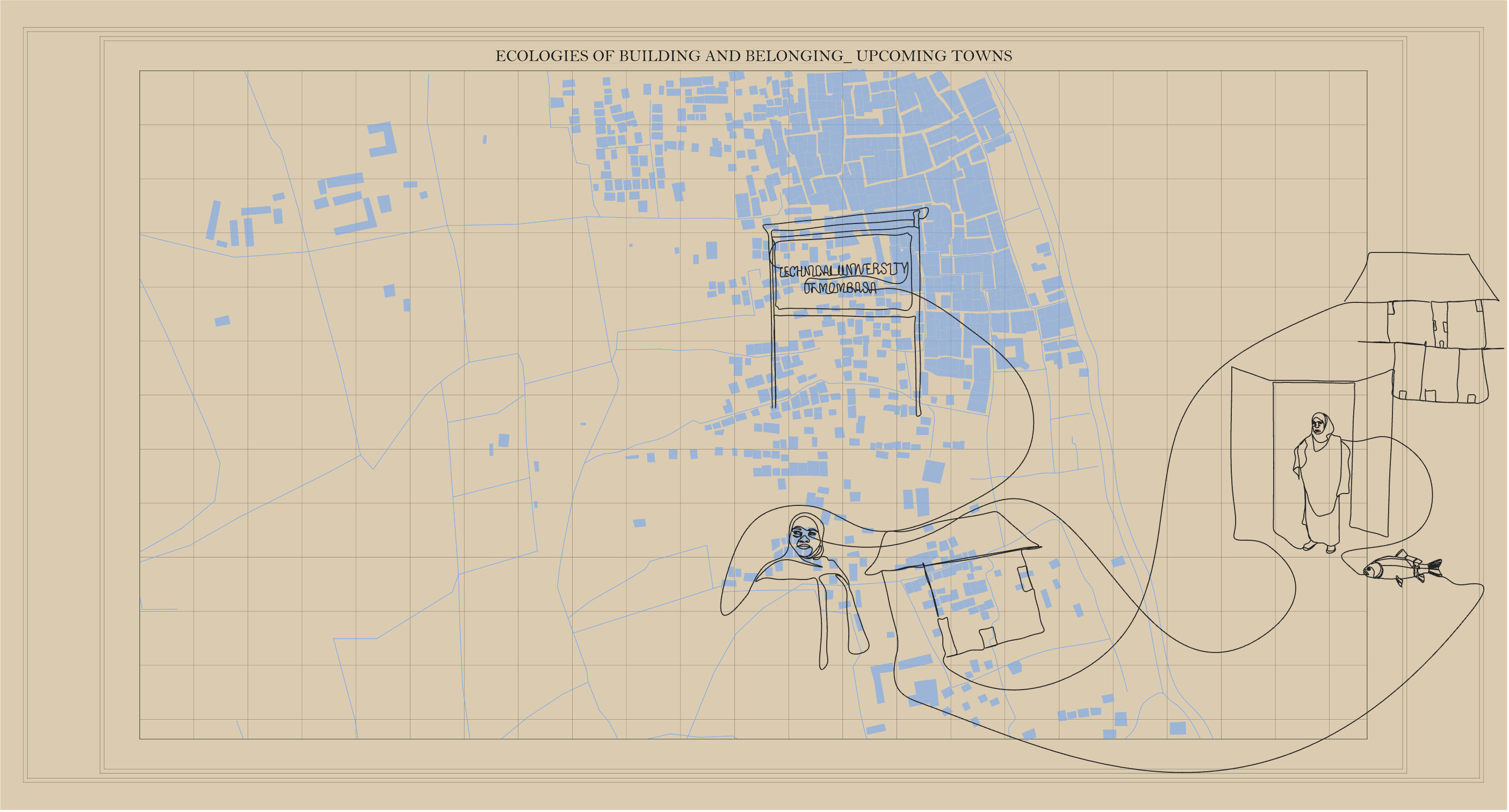

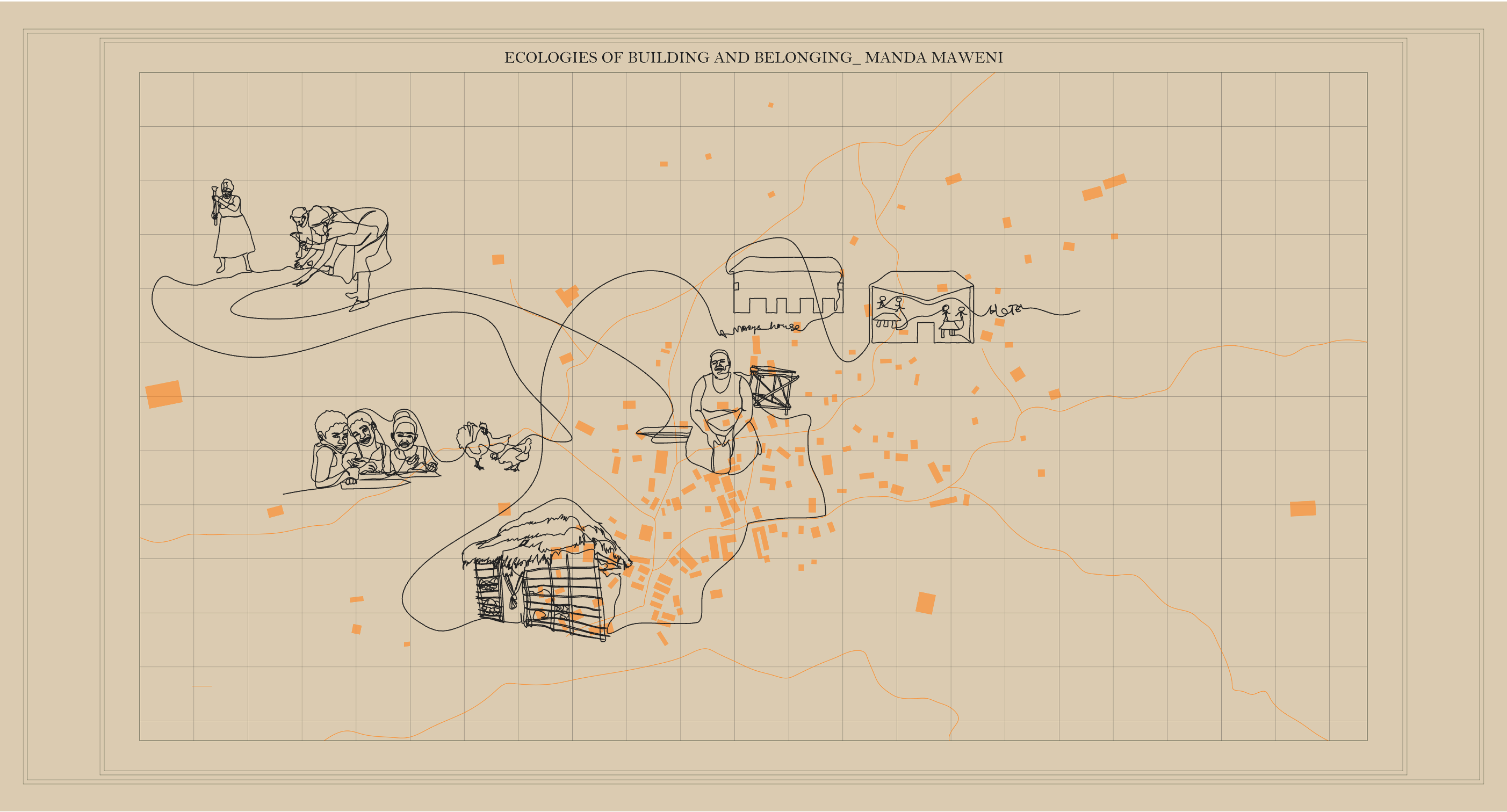

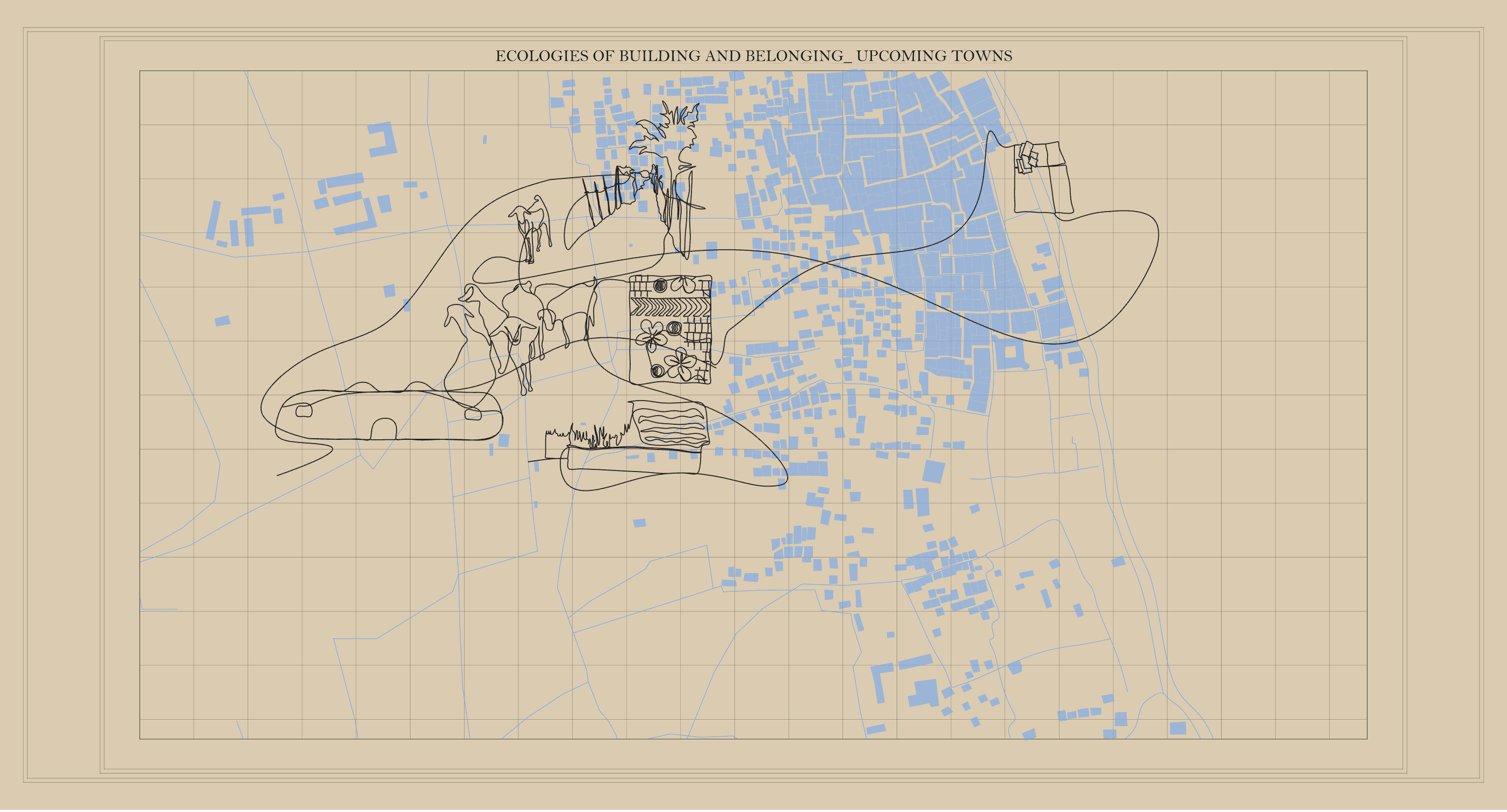

Our urban research with community organizers, stone masons, house builders, home owners, and neighborhood residents combined hand drawing with photography, mapping, interviews and ethnographic walks. We used drawings and maps to convey the ecological relations of belonging that structure these stories. Someone’s sense of belonging cannot be easily pinned on a map or represented in a drawing, yet the dialogical practice of drawing together with community members allowed us to better understand what it means to belong.

Our urban research with community organizers, stone masons, house builders, home owners, and neighborhood residents combined hand drawing with photography, mapping, interviews and ethnographic walks. We used drawings and maps to convey the ecological relations of belonging that structure these stories. Someone’s sense of belonging cannot be easily pinned on a map or represented in a drawing, yet the dialogical practice of drawing together with community members allowed us to better understand what it means to belong.

Nasba’s story

Nasba comes from the coastal area of Kiwayuu, she is Swahili and Muslim. Nasba’s father is a fisherman and her mom owns a shop. She moved to Lamu Island for her studies because the university was close to home. She has been living in Lamu town ever since. Nasba still goes and visit her family in Kiwayuu - she buys groceries in Lamu and brings them to her mother’s shop. She initially lived with relatives and later moved from one rental apartment to another in the town.

Nasba comes from the coastal area of Kiwayuu, she is Swahili and Muslim. Nasba’s father is a fisherman and her mom owns a shop. She moved to Lamu Island for her studies because the university was close to home. She has been living in Lamu town ever since. Nasba still goes and visit her family in Kiwayuu - she buys groceries in Lamu and brings them to her mother’s shop. She initially lived with relatives and later moved from one rental apartment to another in the town.

This is why Nasba says she has so many neighbors. She greets all of them when she walks her streets. Today, she lives in Bombay, one of the new neighborhoods on the outskirts of the historic town. She rents an apartment there and has a close relationship with her neighbors, who she says are like family. In the future, Nasba wants to invest and build a big house back in Kiwayuu, and she also wishes to own a shop there. But she can also imagine living in Lamu, buying a plot of land and building a house of her own.

Mary’s story

Mary was born in central Kangundo in Machakos County. She is Christian and identifies as Kamba. She was brought up in Mpeketoni, where she attended school and learned Kiswahili and English. Her parents could not fully finance her education, so she started working on a farm when she was still young. Her husband was an alcoholic and could not provide for their four children. She divorced him and moved to Maweni for work all by herself. She first lived in a rented house and started working in the quarry to save money for her childrens’ education.

Mary was born in central Kangundo in Machakos County. She is Christian and identifies as Kamba. She was brought up in Mpeketoni, where she attended school and learned Kiswahili and English. Her parents could not fully finance her education, so she started working on a farm when she was still young. Her husband was an alcoholic and could not provide for their four children. She divorced him and moved to Maweni for work all by herself. She first lived in a rented house and started working in the quarry to save money for her childrens’ education.

After ten years of hard work, she saved enough money to take over a restaurant lease and build a house of her own. She is currently renovating it with a tin roof and wishes to build a four-bedroom house. In the future, Mary also wants to build her own restaurant and manage employees in order to welcome more customers. Mary may decide to return to Mpeketoni in the future, but she does not think there will be work for her there.

Dida’s story

Dida was born in the nearby county of Tana River. She is Orma and Muslim. She came to Lamu town with her parents when she was six years old. Her family first lived in the neighborhood of Kandahari. Halima does not have any memories of her home village in Tana River. Her father lives in Witu, a town on the mainland, while her siblings are still living in Lamu Island. For work, Halima sells groundnuts, milk and tobacco in town. Sometimes, she sends her children to sell her products when they are not in school. She lives in her late husband's house together with them.

Dida was born in the nearby county of Tana River. She is Orma and Muslim. She came to Lamu town with her parents when she was six years old. Her family first lived in the neighborhood of Kandahari. Halima does not have any memories of her home village in Tana River. Her father lives in Witu, a town on the mainland, while her siblings are still living in Lamu Island. For work, Halima sells groundnuts, milk and tobacco in town. Sometimes, she sends her children to sell her products when they are not in school. She lives in her late husband's house together with them.

Dida’s house is a temporary structure made out of Makuti. She does not feel secure in her house because the land does not belong to her. It belongs to an old Swahili family of Lamu. She understands she is a squatter and can be told to go away anytime. She aspires to own a plot in Lamu town and build a permanent house of her own.

Projects

Ecologies of Belonging #2301

The Violence in Maweni’s Coral Stones

Maweni, 2023

Maeva Yersin

Download PDF

Maeva Yersin

Download PDF

Anticipating the economic prospects of the new port, the region has witnessed a surge in land speculation, sparking intensifying disputes about belonging in the region. These disputes encompass not only matters of land adjudication and ownership, patronage politics and corruption, but also about the stewardship and transformation of lived-in landscapes and ecologies.

Maweni is a small town nestled on Manda Island within the Lamu archipelago. Since the 1980s, people from various parts of Kenya have flocked to Maweni, attracted by the economic prospects offered by the local quarry. This quarry is pivotal in providing an ongoing supply of coral stones to Lamu town and the surrounding region. Coral stone, as the primary construction material of the town, carries profound cultural significance for Swahili coast residents, tightly interwoven with their sense of belonging, extending along the coastal expanse of Kenya.

Maweni is a small town nestled on Manda Island within the Lamu archipelago. Since the 1980s, people from various parts of Kenya have flocked to Maweni, attracted by the economic prospects offered by the local quarry. This quarry is pivotal in providing an ongoing supply of coral stones to Lamu town and the surrounding region. Coral stone, as the primary construction material of the town, carries profound cultural significance for Swahili coast residents, tightly interwoven with their sense of belonging, extending along the coastal expanse of Kenya.

In contrast to the predominantly Muslim population of the Swahili coast, Maweni's workers and residents, recently counted to be around 2,000 people, are mainly Christian. Many identify as Luo—an ethnic identification of communities initially settled around Lake Victoria in Western Kenya.

![]()

A shipment of coral bricks from Maweni, stacked at Lamu waterfront

A shipment of coral bricks from Maweni, stacked at Lamu waterfront

Postcolonial politics in stone

Coastal Kenya’s prevailing political landscape bears the marks of colonial history. European-imposed racial hierarchies intersect with Arab culture and Muslim notions of belonging within a Christian-dominated Kenya. The ambiguous relationship of coastal communities with “Kenya” can be traced back to the British colonial era when Swahili-speaking communities were racially classified as distinct from Africans. Compounding such clafficiations is the fact that since Kenyan independence, coastal communities have suffered state-led marginalization, manifesting in absent or deteriorating infrastructure, imposed security, and limited education and employment opportunities.

Perceptions of neglect by the postcolonial state have intensified the idea of a distinctive coastal identity, which serves both to gain political legitimacy and establish an alternative narrative of belonging independent of the Kenyan nation-state. How do these complex politics of belonging inhabit building materials such as coral stone?

Perceptions of neglect by the postcolonial state have intensified the idea of a distinctive coastal identity, which serves both to gain political legitimacy and establish an alternative narrative of belonging independent of the Kenyan nation-state. How do these complex politics of belonging inhabit building materials such as coral stone?

Since the 12th century, coastal communities have utilised coral stones to construct houses, tombs, and mosques, thereby transforming coastal towns such as Lamu into powerful nodes of trade and civilisation. Coral stones symbolise the aspiration to be part of the civilisational order of urban Islam, as art historian Prita Meier has shown. They perpetuate the celebratory narrative of Lamu Island as a stone town. However, they also evoke the painful legacy of plantation slavery.

“Coral stone masonry encapsulates political and social tensions, embodying both the violent racial histories of dispossession and the celebratory narratives of belonging to an ecosystem.”

Examining building exclusively through the lens of architecture or development today falls short of capturing these profound historical and political complexities.

“Coral stone masonry encapsulates political and social tensions, embodying both the violent racial histories of dispossession and the celebratory narratives of belonging to an ecosystem.”

Examining building exclusively through the lens of architecture or development today falls short of capturing these profound historical and political complexities.

Reaching Maweni

The commute from Lamu to Maweni begins with a 20-25-minute journey aboard a public boat to Manda Island. From there, the trip then involves a 15-minute ride on the back of a motorbike (known as piki piki). Often, three people share a single motorcycle, navigating muddy and rugged roads that have not been renewed in decades. During rainy days, these roads become treacherous, necessitating slower speeds and an increase in the cost of the ride.

Including waiting times, the journey from Lamu Island to Maweni takes an hour or two, with a total cost ranging between 600 and 800KSH. This overland route is slower but cheaper than going by boat. However, for residents working in Manda Maweni who earn just 1000KSH on a good day, leaving Maweni often means saving up their daily pay for weeks or even months.

Most tourists know Manda Island because this is where the airport is located. Just a few kilometers away, however, the village of Maweni remains a highly marginalized space where quarry workers remain bound to backbreaking labour and have limited mobility options due to high transportation costs.

Nevertheless, material circulates at a frantic pace. Material from the quarrying sites is transported to the shore via donkeys and carts. From there, workers carry the materials on their shoulders onto the boat, which then ferry them to the seafront of Lamu Town.

And just as coral stones are carried out of the village, water containers are carried in. The island has no source of drinking water. Cyclists are often seen transporting yellow water containers brought from Lamu Island. Drinking water makes up a significant portion of household expenses in Maweni.

Mining and Blacknes

Minerals are commonly perceived as inert matter available for exploitation and activation. The logic of extraction and the language used to describe geological processes pervade the experiences of those involved in mining. Geographer Kathryn Yussof has argued that the extraction and commodification of mineral material goes hand in hand with colonial logics of dehumanization. This process is intricately tied to the racialisation of bodies, as the categorisation of blackness is a prerequisite for extracting resources from colonised territories.

Blackness is closely linked to the formation of a subjectivity intentionally distorted by the logic that the violence inherent in resource extraction must be absorbed by black bodies. Blackness, furthermore, is an embodied experience, manifesting itself in journeys and interactions, characterised by the constant movement of bodies, memories, and cultures. These populations possess the capacity to evolve and adapt, "to become different things at different times," reflecting an urban population in perpetual motion or considered available for movement," as urbanist Abdoumaliq Simone writes.

“The concept of Blackness assumes a relational character in Maweni, pertaining to individuals perceived as “immigrants” (colloquially “up-country people”) rather than indigenous residents in the local politics of Lamu.”

“The concept of Blackness assumes a relational character in Maweni, pertaining to individuals perceived as “immigrants” (colloquially “up-country people”) rather than indigenous residents in the local politics of Lamu.”

Ecologies of belonging #2302

Fixators of oppression in space

2023

Cristina De Lucas

Download PDF

Cristina De Lucas

Download PDF

This paper aims to shed light on the connections between property, belonging, and power dynamics in Lamu, Kenya. It relates the historical and conceptual foundations of property to the role of emotions and social negotiation in the construction of belonging. By exploring this interplay between land and belonging, the paper aims to gain a deeper understanding of social hierarchies and identity in Lamu.

Property can be conceptualised as a potent instrument of power, driven by the act of possession akin to domination, thereby ensuring the perpetuation of oppression. Moreover, belonging can be understood as a profound sense of comfort and the emotional responses derived from a harmonious alignment with one's surroundings in terms of behavioural constraints, which are influenced by the directives imposed by a dominant authority. This parallel can be drawn to apprehensions regarding discrimination and exclusion.

Lamu is a vibrant and heterogeneous place characterised by diverse ethnicities, religions, and cultures. With a blend of Islam and Christianity, the region features a fusion of traditions and beliefs. However, despite its rich cultural heritage, Lamu often finds itself stigmatised by Kenya as "the poor, undeveloped one." This discrimination stems from prevailing narratives that undermine the economic and social progress of the area. Additionally, Lamu bears the lasting consequences of British colonisation, having inherited a foreign system of governance that continues to influence its present-day development.

Property can be conceptualised as a potent instrument of power, driven by the act of possession akin to domination, thereby ensuring the perpetuation of oppression. Moreover, belonging can be understood as a profound sense of comfort and the emotional responses derived from a harmonious alignment with one's surroundings in terms of behavioural constraints, which are influenced by the directives imposed by a dominant authority. This parallel can be drawn to apprehensions regarding discrimination and exclusion.

Lamu is a vibrant and heterogeneous place characterised by diverse ethnicities, religions, and cultures. With a blend of Islam and Christianity, the region features a fusion of traditions and beliefs. However, despite its rich cultural heritage, Lamu often finds itself stigmatised by Kenya as "the poor, undeveloped one." This discrimination stems from prevailing narratives that undermine the economic and social progress of the area. Additionally, Lamu bears the lasting consequences of British colonisation, having inherited a foreign system of governance that continues to influence its present-day development.

“Traditionally, the indigenous peoples of Lamu lived in tightly-knit communities where a council of elders played a central role in decision-making processes.”

These respected figures were responsible for ensuring the community's well-being, managing land usage, maintaining security, and overseeing trade activities. They also presided over civil disputes among neighbours and conducted annual religious rituals, many closely tied to economic practices such as farming, livestock rearing, and fishing.

However, the current administrative structure of the government, particularly the presence of the provincial administration, conflicts with these traditional modes of rule.

Consequently, some communities in Lamu have strained relationships with these appointed leaders, resulting in a lack of effective representation and limited opportunities for community participation in decision-making processes. It is within these contexts that housing construction, property dynamics, and the formation of social belonging become salient factors that both influence and are influenced by Lamu's broader power structures.

However, the current administrative structure of the government, particularly the presence of the provincial administration, conflicts with these traditional modes of rule.

“Chiefs, sub-chiefs, and headmen appointed by the government now handle most disputes, effectively sidelining the authority of the Council of Elders. This erosion of power has led to a loss of the indigenous peoples' sense of prior informed consent, as the government-appointed local leaders often fail to consult with the communities they are meant to represent.”

Consequently, some communities in Lamu have strained relationships with these appointed leaders, resulting in a lack of effective representation and limited opportunities for community participation in decision-making processes. It is within these contexts that housing construction, property dynamics, and the formation of social belonging become salient factors that both influence and are influenced by Lamu's broader power structures.

A disenchanted home

As we delve into the exploration of property as an instrument of power, navigating the realm of belonging becomes essential—a concept intricately intertwined with the transmission of narratives surrounding cultural identity. Belonging encompasses the multifaceted tapestry of connections, attachments, and associations individuals forge with spaces, objects, and communities. Within this framework, we can discern how emotional motivations traverse the landscape of property relations.

Scholar Nira Yuval-Davis defines belonging as "an emotional (or even ontological) attachment about feeling 'at home', understood as a safe space." She attests that belonging is always a dynamic process, not a reified fixity, arguing that the latter is only a naturalised construction of a particular hegemonic form of power relations.

However, the feeling of belonging also exists in relation to fixed factors such as family and social roles. These are not only emotional attachments but also structures of power.

Scholar Nira Yuval-Davis defines belonging as "an emotional (or even ontological) attachment about feeling 'at home', understood as a safe space." She attests that belonging is always a dynamic process, not a reified fixity, arguing that the latter is only a naturalised construction of a particular hegemonic form of power relations.

However, the feeling of belonging also exists in relation to fixed factors such as family and social roles. These are not only emotional attachments but also structures of power.

“Romanticising the role of belonging as solely an emotional attachment to childhood memories diminishes the power dynamics at play.”

While it is true that emotional attachments to memories become more pronounced when one is distanced, this heightened visibility results from confronting the feeling of not belonging. These sentiments merely reflect the social comfort of knowing that one's values align with the prevailing social norms of the surroundings.

Communal, state, and private property

In Lamu, the dynamics of land ownership are shaped by a complex interplay of cultural, historical, and political factors. The local population, who predominantly practice Islam, strongly advocates for preserving traditional system of ownership, governed by councils of elders.

The elders hold the power to allocate land use but not ownership. However, the authority of the elders extends beyond land, as they also make decisions pertaining to security trade and oversee annual religious rituals.

However, the administrative structure imposed by the government, particularly through the presence of the provincial administration, means a centralization of power. This shift has resulted in a sense of detachment amongst the people and lack of transparency and accountability in government.

The elders hold the power to allocate land use but not ownership. However, the authority of the elders extends beyond land, as they also make decisions pertaining to security trade and oversee annual religious rituals.

However, the administrative structure imposed by the government, particularly through the presence of the provincial administration, means a centralization of power. This shift has resulted in a sense of detachment amongst the people and lack of transparency and accountability in government.

“The Kenyan government's categorisation of land as Government Land has been exploited by the political and financial elite to gain access to ancestral lands, branding the indigenous communities as ‘squatters’ on their territories.”

A significant portion of Lamu's land, however, is recognised as "community land," intended for communal use and livelihoods. To protect these communal lands, regulations stipulate that they should be held by communities identified based on ethnicity, culture, or similar community interests. Within the community, families and individuals are allocated rights to use the land in perpetuity, with the ultimate ownership vested in the community.

The dynamics of land ownership in Lamu reflect the tension between traditional governance systems, the imposition of colonial structures, the influence of political and financial elites, and the ongoing struggle to protect communal land and livelihoods from land grabbing.

![]()

The dynamics of land ownership in Lamu reflect the tension between traditional governance systems, the imposition of colonial structures, the influence of political and financial elites, and the ongoing struggle to protect communal land and livelihoods from land grabbing.