Mpishi Hula Moshi

How is food a creative medium that articulates Lamu’s oscillating relationships between bodies, places, and time?

Authors:

Nusrat Ahmed Ali

Ummi Haroun

Marie-Jean Malek

Olga Voiushina

Oliver Frayne

A proverb from Lamu that translates as “the cook eats smoke” highlights the hardships of cooking and the fact that the fruits of the cook’s labor are meant for others.

Nusrat Ahmed Ali

Ummi Haroun

Marie-Jean Malek

Olga Voiushina

Oliver Frayne

A proverb from Lamu that translates as “the cook eats smoke” highlights the hardships of cooking and the fact that the fruits of the cook’s labor are meant for others.

This theme traces the stories of food on Lamu Island, where different actors use food as a method to navigate daily challenges, leverage their status, and negotiate gender advantages and social connections by exploring new business opportunities.

Food has become a technology to access earning opportunities for those previously left out, hence reimagining and recreating urban spaces. We examine how this access shapes the uniqueness of Lamu's food culture, fostering value exchange both materially and culturally. This sustains a connection to traditions while providing hope for a future that may or may not be tied to the food business.

![]()

Projects

Mpishi Hula Moshi #2401

Mpishi Hula Moshi

Food Methodologies

With a diverse group of five researchers differing in age, gender, and cultural background, we began by reflecting on our positionality as individuals from various parts of the world. Starting with a simple task of cooking and sharing meals together as team members, food preparation and consumption initiated our journey in order to better connect and understand each other and the focus of our research. This approach aimed to immerse ourselves in local culinary practices and traditions and, depending on our sensory perceptions shaped by the immediate surroundings, to guide and inform our interpretations. The practice of collaborative research has allowed us to better "cook" our research interests, which lies in understanding how food, as an absolute good for all living organisms, entails practices in a social environment that varies from culture to culture.

With a diverse group of five researchers differing in age, gender, and cultural background, we began by reflecting on our positionality as individuals from various parts of the world. Starting with a simple task of cooking and sharing meals together as team members, food preparation and consumption initiated our journey in order to better connect and understand each other and the focus of our research. This approach aimed to immerse ourselves in local culinary practices and traditions and, depending on our sensory perceptions shaped by the immediate surroundings, to guide and inform our interpretations. The practice of collaborative research has allowed us to better "cook" our research interests, which lies in understanding how food, as an absolute good for all living organisms, entails practices in a social environment that varies from culture to culture.

Lamu Foodscape Journey: Mapping Six Weeks of Food Stories

Lamu Foodscape Journey: Mapping Six Weeks of Food Stories Foodscapes are defined by the food practices that create the character of a place. As we were collecting food stories, a map of our research path was developed covering the stories of recipes, ingredients, tools, challenges, and opportunities embodied in the processes of preparing, selling, sharing, and eating food on a daily basis.

Lamu Food Stories

A Space for Aspiration - Farzana’s Story

![]()

Farzana’s kitchen is a cramped, three-square-metre space with no windows or ventilation. It serves as both a workspace for household duties and a small business, with shelves packed with tools for every cooking need. Her equipment blends traditional and modern: a multi-cooker for speed, a gas oven for power cuts, and a charcoal burner as a backup. Limited by space, her tools spill into other rooms.

Farzana’s kitchen is a cramped, three-square-metre space with no windows or ventilation. It serves as both a workspace for household duties and a small business, with shelves packed with tools for every cooking need. Her equipment blends traditional and modern: a multi-cooker for speed, a gas oven for power cuts, and a charcoal burner as a backup. Limited by space, her tools spill into other rooms.

For Farzana, cooking is both a duty and a creative outlet. She personalizes meals with secret ingredients, adapts broken tools, and tries TikTok-inspired recipes. Cooking lets her care for her family’s health and gives her a rare space for self-expression, constrained by cultural traditions in Lamu. Her investment in modern tools reflects her desire to ease her domestic load and expand her small food business from home, symbolizing a broader tension between tradition and modernity where personal and professional aspirations meet.

This dual pursuit - seeking efficiency in household chores while aspiring to economic activities centered on the home space reflects a larger picture in Lamu. It is a nuanced balance between tradition and modernity a negotiation of space where personal and professional aspirations converge.

Biryani Night - The Story of Many Hands for One Dish

In our journey to unveil the different scales and spaces of food-making, the preparation of wedding food marks a traditional festivity rich with socio-cultural stories and connections. In a one-night setup to prepare biryani, a traditional wedding meal, an often invisible social infrastructure comes to life where private and commercial aspects merge while maintaining the societal hierarchy. In this setup, the top supervisory roles were held by the adult men of the family, who oversaw the preparations.

Below them were two paid chefs from Mombasa, assisted by younger male family members or, in wealthier families, hired helpers. The most basic tasks were assigned to women, who were close family members or friends. Biryani preparation becomes a rare and valuable opportunity for women to connect and socialize away from their daily lives, which are still shaped by strict social norms and extensive domestic responsibilities. The community hall nonetheless transforms into a space for women to breathe, engage in self-making, and bond socially through chanting, dancing, and small conversations around food trays.

Lost Recipes, Lost Connections - A Recipe’s Story

With our desire to explore Lamu's traditional dishes through hands-on learning, we focused on local, typical ingredients that require simple preparation. Bananas, coconut, and sugar seemed simple in theory but led us to discover the creativity and variety employed by locals to create two distinct dishes: Mazu (or Ndizi za Nazi), a familiar dessert for Lamu residents, and Mboko, a fading recipe at risk of being forgotten.

What began as a goal to exchange knowledge, practices, food, and joy within our group evolved into recording one of many unwritten food archives that are gradually disappearing, along with the stories of the women who invented and once cooked these dishes.

A Space of Experimentation - Asma’s Story

Carrying on her family’s heritage in the food business and driven by a desire to have a self-independent work, Asma—fondly known as “Mama Ntilie” by those who visit her small outdoor kitchen—introduces a new dimension of Lamu food stories.

For 24 years, her corner of the street witnessed her innovations in the Lamu food business, demonstrated by the arrangement of her cooking platform to accommodate both the family business and her customers’ needs.

The display of her cooking tools, the preparation of the jiko for a live cooking experience, and the promotion of various homemade dishes on her small table—some made by other women in the family— all contribute to transforming the place into a warm and comfortable dine-in experience for repeated customers, embodying the genuine warmth and hospitality of a true ‘Mama Ntilie.’

The display of her cooking tools, the preparation of the jiko for a live cooking experience, and the promotion of various homemade dishes on her small table—some made by other women in the family— all contribute to transforming the place into a warm and comfortable dine-in experience for repeated customers, embodying the genuine warmth and hospitality of a true ‘Mama Ntilie.’

A Space of Resilience - Fahita’s Story

We approached Fahita to learn more about her mahamri, by some accounts the best mahamri in town. In a quiet, narrow alley blackened from years of wood smoke, Fahita makes mahamri each day. She buys the ingredients from the same place—she has her person. She cuts and shapes them here, but the dough is mixed off-site at her in-laws' shop, where they have a standing mixer suitable for larger amounts of dough needed for her small mahamri business.

We learn that one aspect that makes this mahamri popular is that they taste, look, and feel homemade—something that gets lost in commercialized baking.

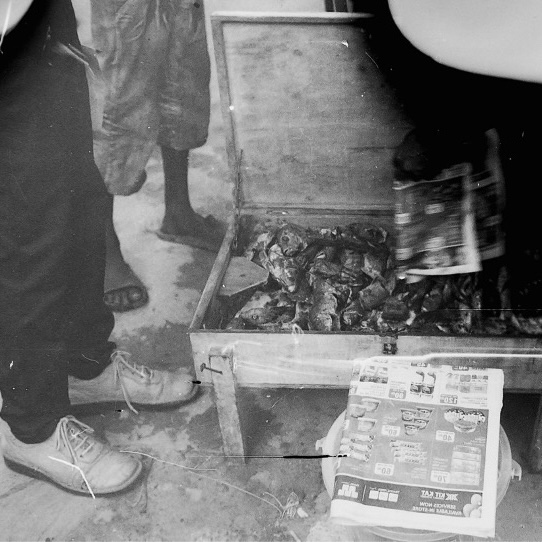

The steps of mahamri making start inside the house—shaping the triangular mahamri, rolling a small disc, and cutting it into quarters, which are then stacked and set aside. Fahita then moves outside to her usual corner to start the frying. As she begins frying she becomes quiet. The dough triangles are tossed into the oil; they inflate and become a dark orange-gold before being turned out into a colander to drain off excess oil. Fahita says a small prayer each time she fries another batch. We depart with hot mahamri wrapped in newspaper advertising discounts on electronics.

The steps of mahamri making start inside the house—shaping the triangular mahamri, rolling a small disc, and cutting it into quarters, which are then stacked and set aside. Fahita then moves outside to her usual corner to start the frying. As she begins frying she becomes quiet. The dough triangles are tossed into the oil; they inflate and become a dark orange-gold before being turned out into a colander to drain off excess oil. Fahita says a small prayer each time she fries another batch. We depart with hot mahamri wrapped in newspaper advertising discounts on electronics.

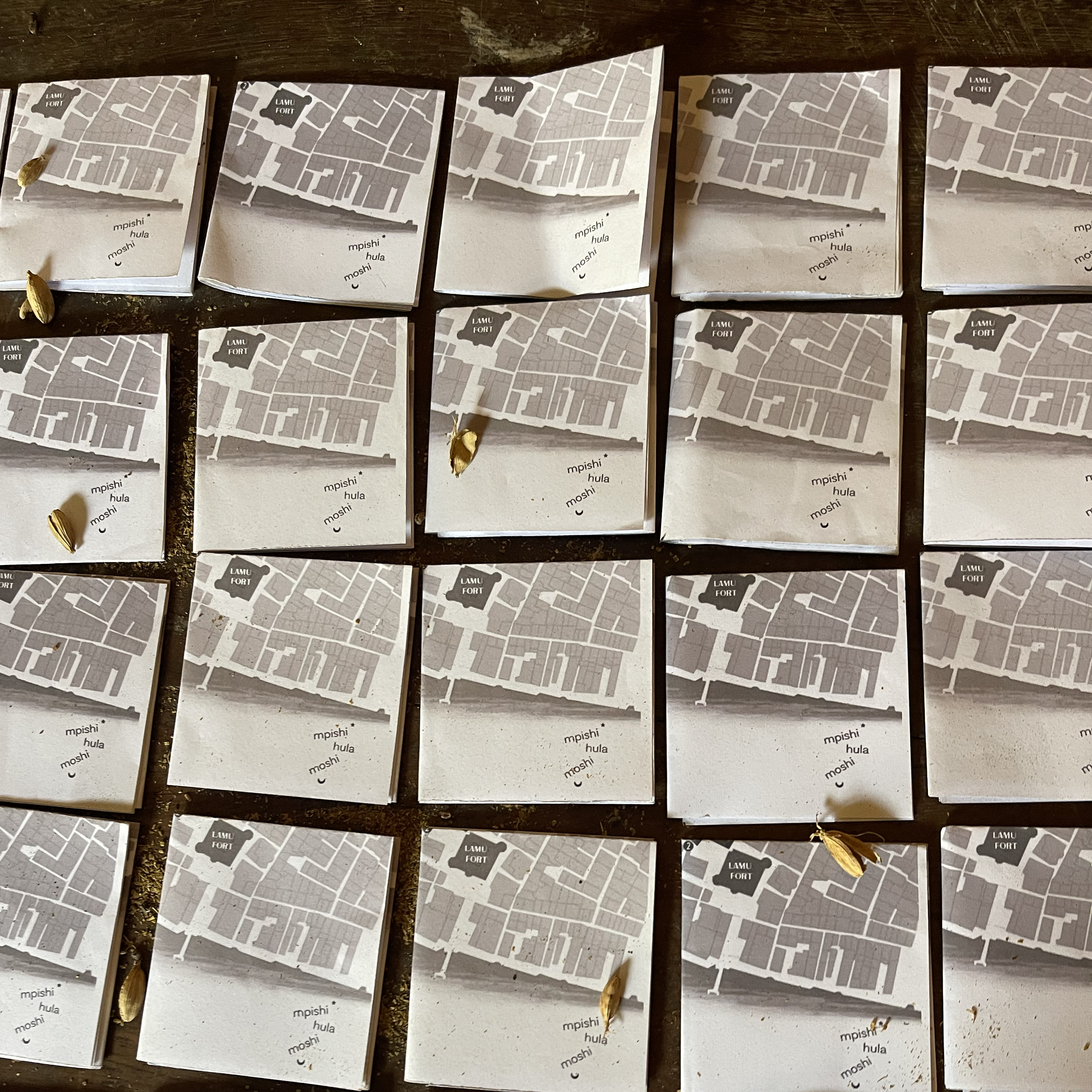

Exhibition

The stories and characters featured on this page became part of an exhibition at the Lamu Fort Museum in May 2024, where the collaborative work was shared with the people of Lamu. A folded map served as a key to the exhibit, allowing visitors to journey from story to story - not only within the exhibition but also to discover these places and people throughout the city.

By gathering recipes, stories, and symbolic objects, the exhibition aimed to show how food bridges the global and local, uniting past traditions with modern technologies, personal expressions with collective identities.

Through preparing, sharing, and enjoying food, it becomes a creative medium that reimagines the connections between bodies, places, and time.