Heritage under Transformation

How do women transform long-standing traditions of dwelling and home-building in Lamu? How does heritage matter in the context of a rapidly changing urban landscape?

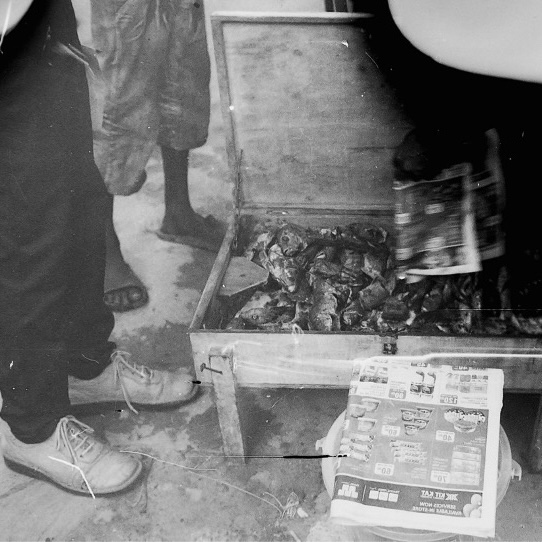

Alleys in old town (L) and new neighborhoods (Kashmir) (R)

Alleys in old town (L) and new neighborhoods (Kashmir) (R)Recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, Lamu’s ancient Stone Town harbours longstanding dwelling traditions. Yet, the town has experienced fast urban growth in recent years, with the emergence of entirely new neighbourhoods built on the once-agricultural outskirts. How does the old Lamu inhabit this new Lamu? What does dwelling culture mean in this rapidly changing context?

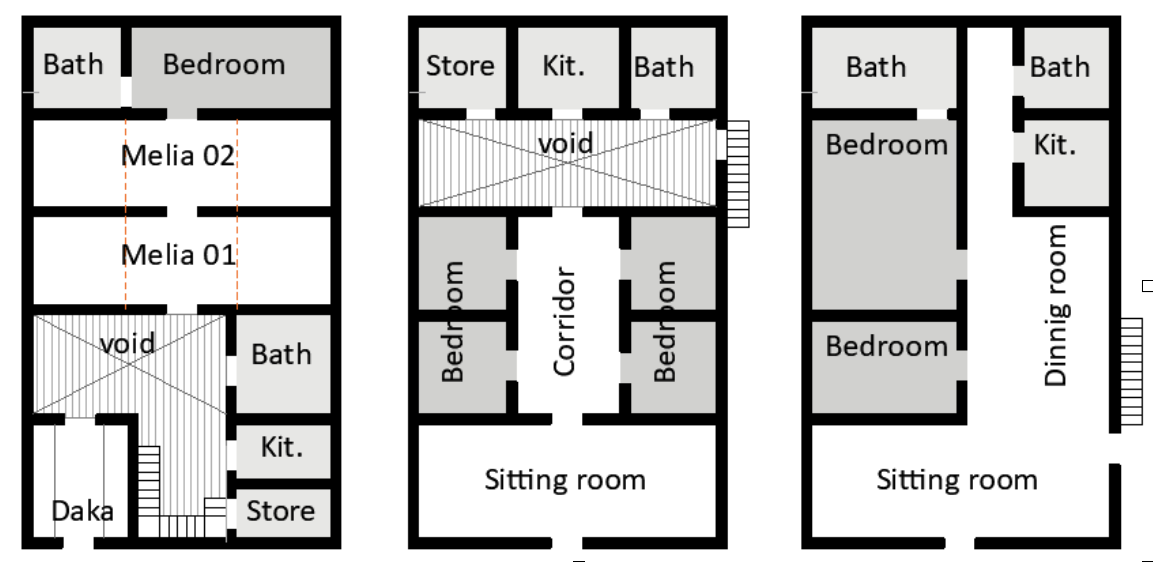

The new homes of Lamu’s emerging neighbourhoods may still be built using coral stone and mangrove wood, but they also feature new kinds of spaces and accommodate new uses. This theme explores this ongoing transformation of domestic cultures and home-building, focusing on the roles and practices of women in Lamu’s historic town as well as its new residential neighborhoods.

The new homes of Lamu’s emerging neighbourhoods may still be built using coral stone and mangrove wood, but they also feature new kinds of spaces and accommodate new uses. This theme explores this ongoing transformation of domestic cultures and home-building, focusing on the roles and practices of women in Lamu’s historic town as well as its new residential neighborhoods.

Using semi-structured interviews and architectural methods of analysis, our research shows how women negotiate with home builders (fundi) to create domestic spaces that meet their needs even as they aim to preserve their inheritance. In doing so, we emphasise the importance of those who inhabit and transform Lamu’s built heritage. This perspective contributes to the ongoing dialogue about heritage and sustainable development in Lamu.

Projects

Heritage under Transformation

#2305

Dwelling in Transition

#2305

Dwelling in Transition

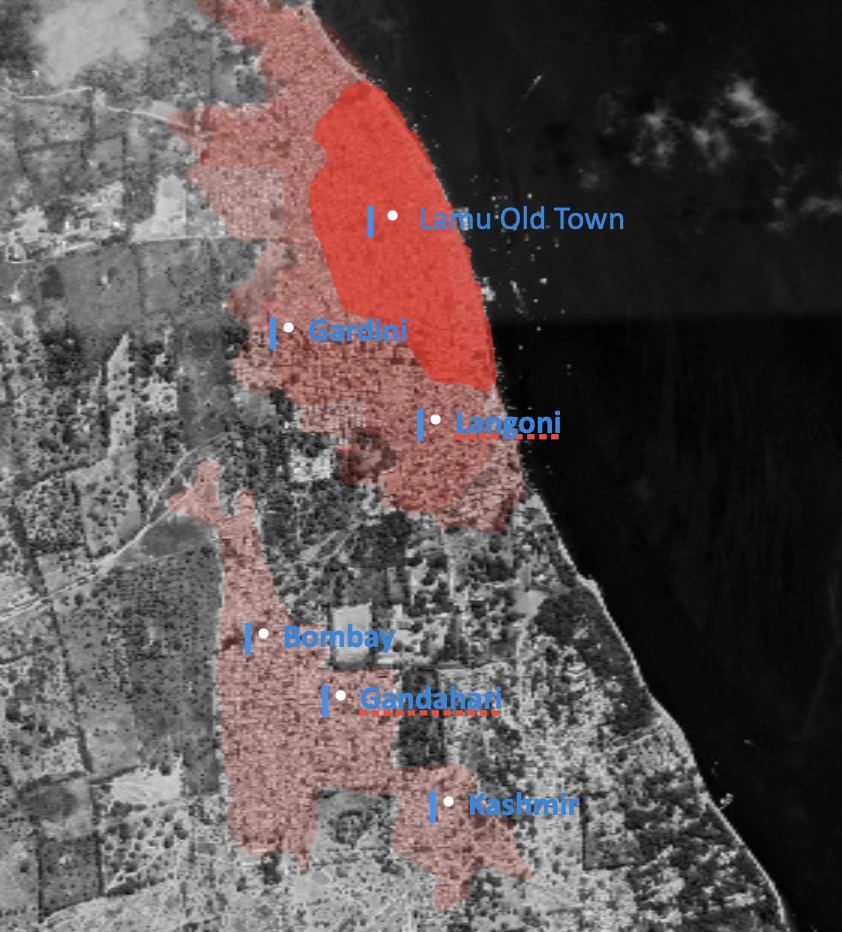

A key element of the ancient Lamu stone house is the melia setup. This sequence of rooms is characterised by a lack of clear demarcations for multiple uses, fostering the flexible uses of domectic space. The absence of assigned rooms promotes communal use, even for individuals valuing privacy within their homes.

Lamu’s famous Stone Town embraces such adaptive use. Families divide houses among themselves or repurpose the structures over time. As families grow, houses expand; multi-story structures are constructed to accommodate the increasing number of family members, reflecting the cultural tradition of mita emphasising collective living.

Lamu’s famous Stone Town embraces such adaptive use. Families divide houses among themselves or repurpose the structures over time. As families grow, houses expand; multi-story structures are constructed to accommodate the increasing number of family members, reflecting the cultural tradition of mita emphasising collective living.

Dwelling entails not just the physical structure of a house but also the profound social, cultural, and emotional connections individuals establish with their living spaces.

Women assume a central role within these spaces as primary users and decision-makers in household arrangements. Furthermore, the expertise of builders contributes to the configuration of these spaces, thus exerting a considerable influence on their design and functionality.

Recognising the cultural and historical layers embedded within these homes allows for shaping future spaces that are both culturally meaningful and sustainable over time.

The collaborative synergy between women, serving as users and decision-makers, and house builders, with their expertise, culminates in the creation of living spaces that both reflect and accommodate the unique cultural and social dynamics of Lamu.

Recognising the cultural and historical layers embedded within these homes allows for shaping future spaces that are both culturally meaningful and sustainable over time.

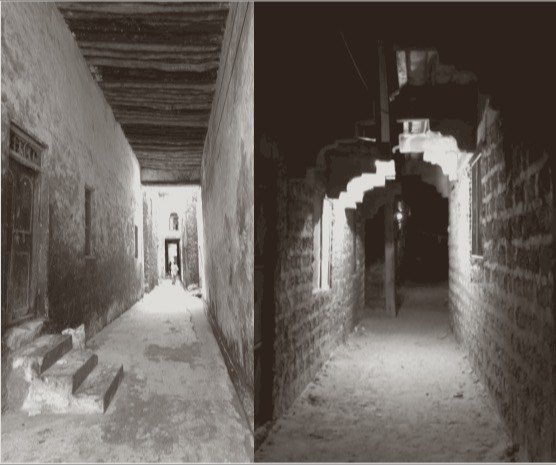

The emergence of new neighbourhoods

Lamu town comprises three areas in terms of architectural and urban morphology. The Stone Town, object of the UNESCO world heritage designation, is the oldest part of town, and is historically home to the town’s merchant elite. The immediately adjacent neighborhoods of Langoni and Gardeni are former agricultural areas that became popular, less affluent neighborhoods. They were initially built up with wattle-and-daub constructions, which have more recently been replaced with more permanent constructions including modern apartment buildings. The third type of built fabric in Lamu are the new neighborhoods that have emerged on the outskirts, roughly since the 2000s. These areas tend to have homes built on regularized plots, with a size of 30x40 feet. Lamu residents referred to these areas as "bushy" or "forest" before they evolved into well-defined neighbourhoods.

Historically, Stone Town housed the wealthier segments of society, while mud and thatch construction accommodated the less affluent.

These two distinct forms of domestic architecture, however, are interconnected and belong to the same cultural continuum. Lamu residents capture this relationship with the saying "Msitu ni ule ule komba ni wengine," which translates to "the forest is the same, but with different bushes." The differentiation of these two areas has gradually faded away with the replacement of mud by coral blocks.

The notion that stone signifies Arab culture and thatch represents African culture is erroneous, as Lamu's inhabitants have diverse ethnic backgrounds, and construction materials do not correspond to specific racial categories.

Lamu old and new neighborhoods boundary in 2003

Lamu old and new neighborhoods boundary in 2003However, stone houses still symbolise social status and lineage, providing a sense of permanence and privacy within Swahili culture. These stone houses did not arise from an ideal prototype but rather evolved through the amalgamation of materials and practices by various homebuilders over time. They emerged due to the blending and referencing of the existing tradition of using coral stone for the houses of the merchant elite, as art historian Prita Meier has shown.

The same architectural styles persisted in Lamu for centuries in both towns and houses, characterised by a significant contrast between stone and mud constructions. Lifestyle disparities between the stone and mud towns were evident in the character of the main street, with Langoni displaying a higher density of shops that gradually decreased in number but increased in size as one moved closer to the area of Mkomani.

What changes in spatial organisation, if any, have occurred with this growth?

The new areas, with their regular plot sizes of 30x40 feet, feature new house types. At the same time, many factors influencing the organisation of domestic space remained relatively unchanged in Lamu over centuries. The same construction methods, materials, climate, and plot size continued to shape its domestic culture. However, there were significant shifts in women’s expectations, comfort, and need for seclusion and privacy, and these have become more pronounced in recent decades.

Women & domestic culture

Exploring women's perspectives within Lamu’s evolving domestic culture builds upon feminist approaches to architecture and urbanism. These studies displaced the predominantly masculine lens of previous scholarship, which often reproduced patriarchal conceptions of dwelling culture and urban development.

Dwelling undergoes a natural evolution as inhabitants personalise their homes to align with their preferences and actively adapt their living spaces, fostering a sense of accomplishment, self-expression, and autonomy. The concept of home gradually takes on deeper dimensions, intertwining with a profound sense of belonging, cherished memories, and past life encounters. The presence of relationships, residential history, familiarity, and established routines collectively cultivate the comforting feeling of being truly "at home."

Exploring women's perspectives within Lamu’s evolving domestic culture builds upon feminist approaches to architecture and urbanism. These studies displaced the predominantly masculine lens of previous scholarship, which often reproduced patriarchal conceptions of dwelling culture and urban development.

Dwelling undergoes a natural evolution as inhabitants personalise their homes to align with their preferences and actively adapt their living spaces, fostering a sense of accomplishment, self-expression, and autonomy. The concept of home gradually takes on deeper dimensions, intertwining with a profound sense of belonging, cherished memories, and past life encounters. The presence of relationships, residential history, familiarity, and established routines collectively cultivate the comforting feeling of being truly "at home."

Amid the numerous studies investigating various facets of dwelling, this research probes women's roles and practices as both agents of change and guardians of cultural heritage. By actively immersing ourselves in their everyday practices and negotiations with house builders, this study examines the evolution of domestic culture and explores how meanings and values associated with home have evolved over time.

Examining the intricate interplay among architecture, gender roles, and spatial dynamics reveals entrenched biases, the profound impact of gender on social and spatial constructs, and some unexpected consequences of urban development.

Typical Stone house (L), typical Swahili house from Kashmir and Langoni (M), and what so-called modern house from Melimani