Mpishi Hula Moshi

How is food a creative medium that articulates Lamu’s oscillating relationships between bodies, places, and time?

Authors:

Nusrat Ahmed Ali

Ummi Haroun

Marie-Jean Malek

Olga Voiushina

Oliver Frayne

A proverb from Lamu that translates as “the cook eats smoke” highlights the hardships of cooking and the fact that the fruits of the cook’s labor are meant for others.

Nusrat Ahmed Ali

Ummi Haroun

Marie-Jean Malek

Olga Voiushina

Oliver Frayne

A proverb from Lamu that translates as “the cook eats smoke” highlights the hardships of cooking and the fact that the fruits of the cook’s labor are meant for others.

This theme traces the stories of food on Lamu Island, where different actors use food as a method to navigate daily challenges, leverage their status, and negotiate gender advantages and social connections by exploring new business opportunities.

Food has become a technology to access earning opportunities for those previously left out, hence reimagining and recreating urban spaces. We examine how this access shapes the uniqueness of Lamu's food culture, fostering value exchange both materially and culturally. This sustains a connection to traditions while providing hope for a future that may or may not be tied to the food business.

![]()

Projects

Mpishi Hula Moshi #2401

Mpishi Hula Moshi

Food Methodologies

With a diverse group of five researchers differing in age, gender, and cultural background, we began by reflecting on our positionality as individuals from various parts of the world. Starting with a simple task of cooking and sharing meals together as team members, food preparation and consumption initiated our journey in order to better connect and understand each other and the focus of our research. This approach aimed to immerse ourselves in local culinary practices and traditions and, depending on our sensory perceptions shaped by the immediate surroundings, to guide and inform our interpretations. The practice of collaborative research has allowed us to better "cook" our research interests, which lies in understanding how food, as an absolute good for all living organisms, entails practices in a social environment that varies from culture to culture.

With a diverse group of five researchers differing in age, gender, and cultural background, we began by reflecting on our positionality as individuals from various parts of the world. Starting with a simple task of cooking and sharing meals together as team members, food preparation and consumption initiated our journey in order to better connect and understand each other and the focus of our research. This approach aimed to immerse ourselves in local culinary practices and traditions and, depending on our sensory perceptions shaped by the immediate surroundings, to guide and inform our interpretations. The practice of collaborative research has allowed us to better "cook" our research interests, which lies in understanding how food, as an absolute good for all living organisms, entails practices in a social environment that varies from culture to culture.

Lamu Foodscape Journey: Mapping Six Weeks of Food Stories

Lamu Foodscape Journey: Mapping Six Weeks of Food Stories Foodscapes are defined by the food practices that create the character of a place. As we were collecting food stories, a map of our research path was developed covering the stories of recipes, ingredients, tools, challenges, and opportunities embodied in the processes of preparing, selling, sharing, and eating food on a daily basis.

Lamu Food Stories

A Space for Aspiration - Farzana’s Story

![]()

Farzana’s kitchen is a cramped, three-square-metre space with no windows or ventilation. It serves as both a workspace for household duties and a small business, with shelves packed with tools for every cooking need. Her equipment blends traditional and modern: a multi-cooker for speed, a gas oven for power cuts, and a charcoal burner as a backup. Limited by space, her tools spill into other rooms.

Farzana’s kitchen is a cramped, three-square-metre space with no windows or ventilation. It serves as both a workspace for household duties and a small business, with shelves packed with tools for every cooking need. Her equipment blends traditional and modern: a multi-cooker for speed, a gas oven for power cuts, and a charcoal burner as a backup. Limited by space, her tools spill into other rooms.

For Farzana, cooking is both a duty and a creative outlet. She personalizes meals with secret ingredients, adapts broken tools, and tries TikTok-inspired recipes. Cooking lets her care for her family’s health and gives her a rare space for self-expression, constrained by cultural traditions in Lamu. Her investment in modern tools reflects her desire to ease her domestic load and expand her small food business from home, symbolizing a broader tension between tradition and modernity where personal and professional aspirations meet.

This dual pursuit - seeking efficiency in household chores while aspiring to economic activities centered on the home space reflects a larger picture in Lamu. It is a nuanced balance between tradition and modernity a negotiation of space where personal and professional aspirations converge.

Biryani Night - The Story of Many Hands for One Dish

In our journey to unveil the different scales and spaces of food-making, the preparation of wedding food marks a traditional festivity rich with socio-cultural stories and connections. In a one-night setup to prepare biryani, a traditional wedding meal, an often invisible social infrastructure comes to life where private and commercial aspects merge while maintaining the societal hierarchy. In this setup, the top supervisory roles were held by the adult men of the family, who oversaw the preparations.

Below them were two paid chefs from Mombasa, assisted by younger male family members or, in wealthier families, hired helpers. The most basic tasks were assigned to women, who were close family members or friends. Biryani preparation becomes a rare and valuable opportunity for women to connect and socialize away from their daily lives, which are still shaped by strict social norms and extensive domestic responsibilities. The community hall nonetheless transforms into a space for women to breathe, engage in self-making, and bond socially through chanting, dancing, and small conversations around food trays.

Lost Recipes, Lost Connections - A Recipe’s Story

With our desire to explore Lamu's traditional dishes through hands-on learning, we focused on local, typical ingredients that require simple preparation. Bananas, coconut, and sugar seemed simple in theory but led us to discover the creativity and variety employed by locals to create two distinct dishes: Mazu (or Ndizi za Nazi), a familiar dessert for Lamu residents, and Mboko, a fading recipe at risk of being forgotten.

What began as a goal to exchange knowledge, practices, food, and joy within our group evolved into recording one of many unwritten food archives that are gradually disappearing, along with the stories of the women who invented and once cooked these dishes.

A Space of Experimentation - Asma’s Story

Carrying on her family’s heritage in the food business and driven by a desire to have a self-independent work, Asma—fondly known as “Mama Ntilie” by those who visit her small outdoor kitchen—introduces a new dimension of Lamu food stories.

For 24 years, her corner of the street witnessed her innovations in the Lamu food business, demonstrated by the arrangement of her cooking platform to accommodate both the family business and her customers’ needs.

The display of her cooking tools, the preparation of the jiko for a live cooking experience, and the promotion of various homemade dishes on her small table—some made by other women in the family— all contribute to transforming the place into a warm and comfortable dine-in experience for repeated customers, embodying the genuine warmth and hospitality of a true ‘Mama Ntilie.’

The display of her cooking tools, the preparation of the jiko for a live cooking experience, and the promotion of various homemade dishes on her small table—some made by other women in the family— all contribute to transforming the place into a warm and comfortable dine-in experience for repeated customers, embodying the genuine warmth and hospitality of a true ‘Mama Ntilie.’

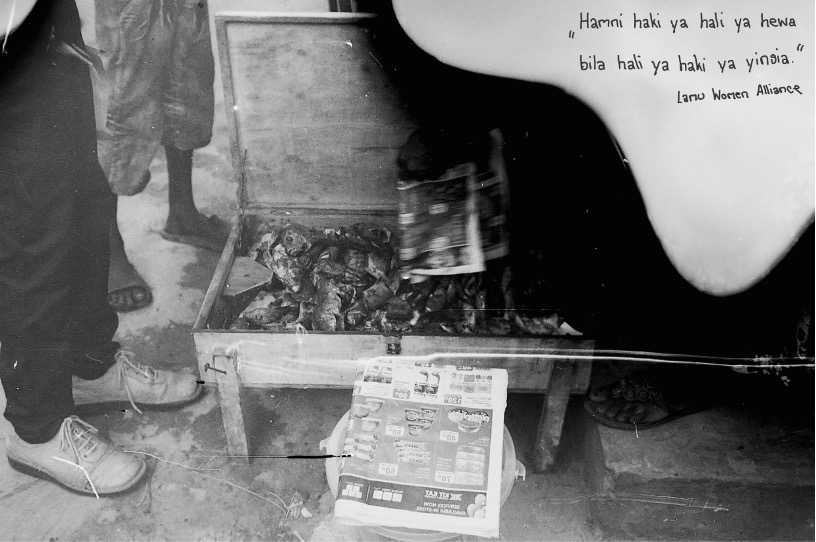

A Space of Resilience - Fahita’s Story

We approached Fahita to learn more about her mahamri, by some accounts the best mahamri in town. In a quiet, narrow alley blackened from years of wood smoke, Fahita makes mahamri each day. She buys the ingredients from the same place—she has her person. She cuts and shapes them here, but the dough is mixed off-site at her in-laws' shop, where they have a standing mixer suitable for larger amounts of dough needed for her small mahamri business.

We learn that one aspect that makes this mahamri popular is that they taste, look, and feel homemade—something that gets lost in commercialized baking.

The steps of mahamri making start inside the house—shaping the triangular mahamri, rolling a small disc, and cutting it into quarters, which are then stacked and set aside. Fahita then moves outside to her usual corner to start the frying. As she begins frying she becomes quiet. The dough triangles are tossed into the oil; they inflate and become a dark orange-gold before being turned out into a colander to drain off excess oil. Fahita says a small prayer each time she fries another batch. We depart with hot mahamri wrapped in newspaper advertising discounts on electronics.

The steps of mahamri making start inside the house—shaping the triangular mahamri, rolling a small disc, and cutting it into quarters, which are then stacked and set aside. Fahita then moves outside to her usual corner to start the frying. As she begins frying she becomes quiet. The dough triangles are tossed into the oil; they inflate and become a dark orange-gold before being turned out into a colander to drain off excess oil. Fahita says a small prayer each time she fries another batch. We depart with hot mahamri wrapped in newspaper advertising discounts on electronics.

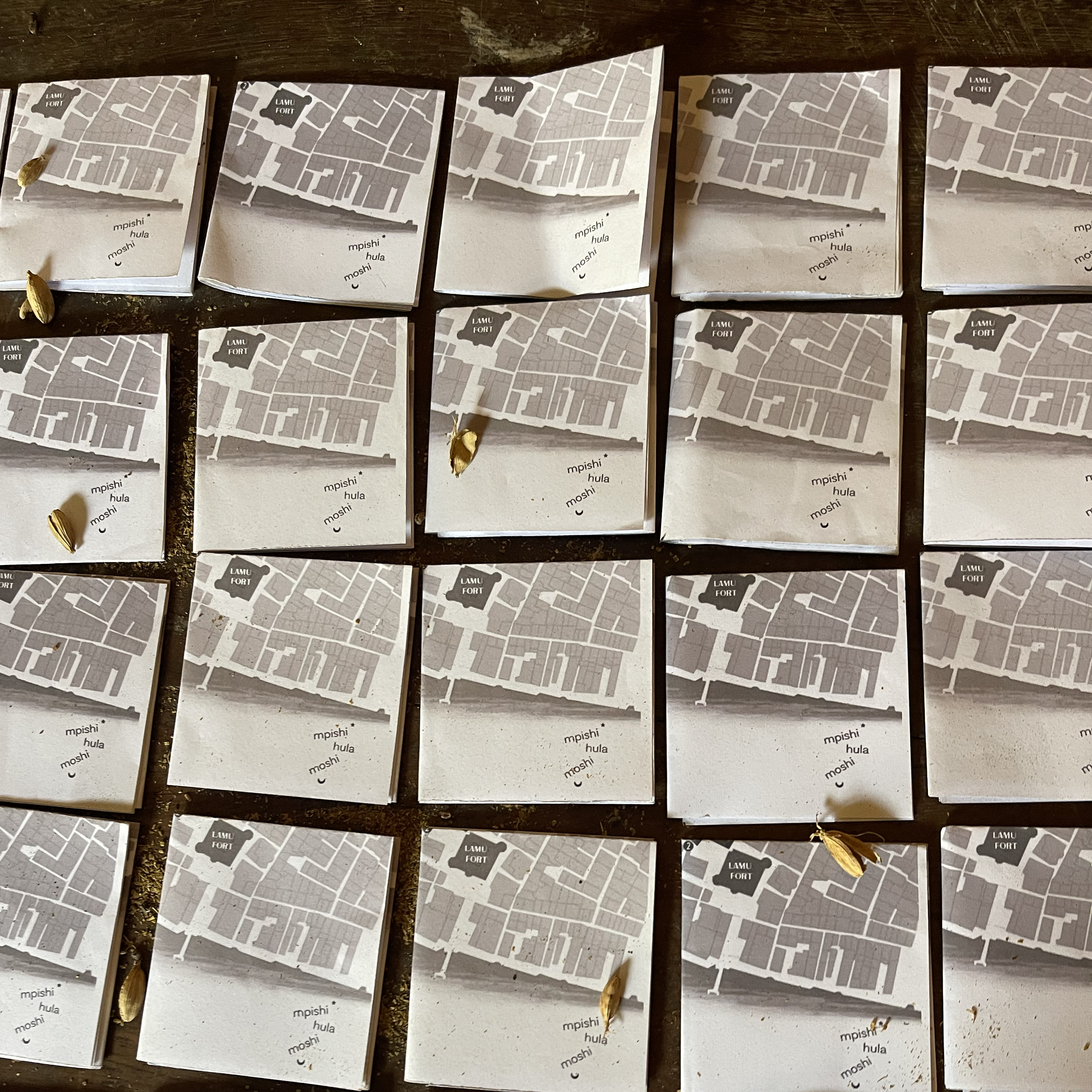

Exhibition

The stories and characters featured on this page became part of an exhibition at the Lamu Fort Museum in May 2024, where the collaborative work was shared with the people of Lamu. A folded map served as a key to the exhibit, allowing visitors to journey from story to story - not only within the exhibition but also to discover these places and people throughout the city.

By gathering recipes, stories, and symbolic objects, the exhibition aimed to show how food bridges the global and local, uniting past traditions with modern technologies, personal expressions with collective identities.

Through preparing, sharing, and enjoying food, it becomes a creative medium that reimagines the connections between bodies, places, and time.

Mama na Bahari

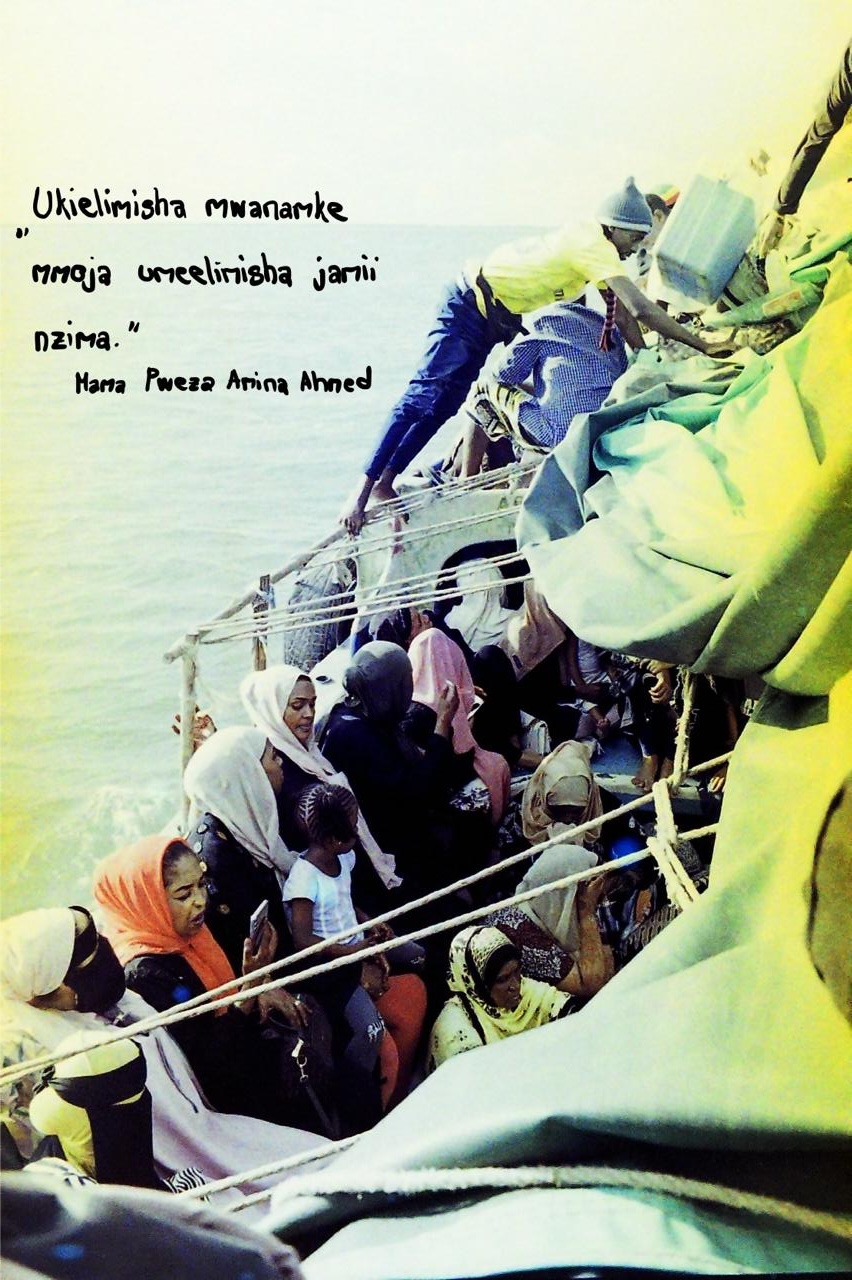

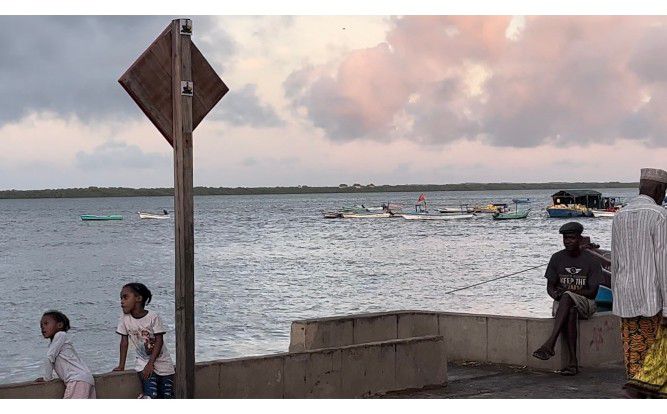

“Mama na Bahari” investigates the transformative role of women in Lamu’s fishing industry, particularly through their involvement in projects like sustainable octopus closures.

It asks, how do social identities and the community roles of women in Lamu evolve through their engagement in the fishing industry? How do gender dynamics and cultural practices influence women's roles and participation in environmental conservation efforts in Lamu, Kenya? By examining these initiatives and women’s activism, our research highlights how women’s participation is reshaping community structures, redefining, and challenging traditional roles. These sustainable practices not only enhance environmental conservation but also elevate women’s standing within the community, contesting long-held gender norms.

![]()

The research underscores the pivotal contributions of women in fostering economic adaptability and environmental stewardship in Lamu. Through these initiatives, women become agents of change, reshaping local perceptions of gender roles and actively contributing to Lamu’s socio-economic landscape.

The research underscores the pivotal contributions of women in fostering economic adaptability and environmental stewardship in Lamu. Through these initiatives, women become agents of change, reshaping local perceptions of gender roles and actively contributing to Lamu’s socio-economic landscape.

This project offers a comprehensive view of how women are reimagining their place within the fishing industry, interweaving the intersections of gender, economy, and environmental sustainability to build a more inclusive and empowered future.

Projects

Introduction

This project investigates the intersection of Islamic feminism, decolonial feminism, and environmental justice in Lamu, Kenya, with a focus on women’s roles in environmental conservation and social justice within the fishing industry.

Using an intersectional approach, it highlights the complex socio-cultural and economic barriers that shape women’s experiences, revealing the ways in which gender, environment, and power are interconnected.

![]()

This project investigates the intersection of Islamic feminism, decolonial feminism, and environmental justice in Lamu, Kenya, with a focus on women’s roles in environmental conservation and social justice within the fishing industry.

Using an intersectional approach, it highlights the complex socio-cultural and economic barriers that shape women’s experiences, revealing the ways in which gender, environment, and power are interconnected.

Through interviews, group discussions, participatory observations, and literature review, the study emphasizes the critical role of women in addressing climate-related challenges, such as droughts and floods, which disproportionately impact their lives and livelihoods.

The Mama na Bahari exhibition serves as a central element of the research, demonstrating the significant influence of women’s conservation efforts and their contributions to both the environment and society.

Findings suggest that environmental justice in Lamu cannot be achieved without gender justice, and this paper advocates for an integrated approach that combines both.

Sustainable Futures

Women in Lamu’s fishing industry face numerous challenges, particularly those exacerbated by climate change. These include not only environmental pressures like rising sea levels and unpredictable weather patterns but also socio-cultural restrictions that limit their mobility and participation in the industry.

The paper documents that women, who are often responsible for household duties, are more vulnerable during environmental crises. During floods, for example, women’s caregiving roles increase their exposure to danger, limiting their ability to seek safety. Moreover, health risks for women are amplified, as climate change contributes to increased incidences of stillbirths and diseases such as malaria and Zika. The intersection of these issues underscores the urgent need for gender-sensitive policies that recognize the unique vulnerabilities faced by women.

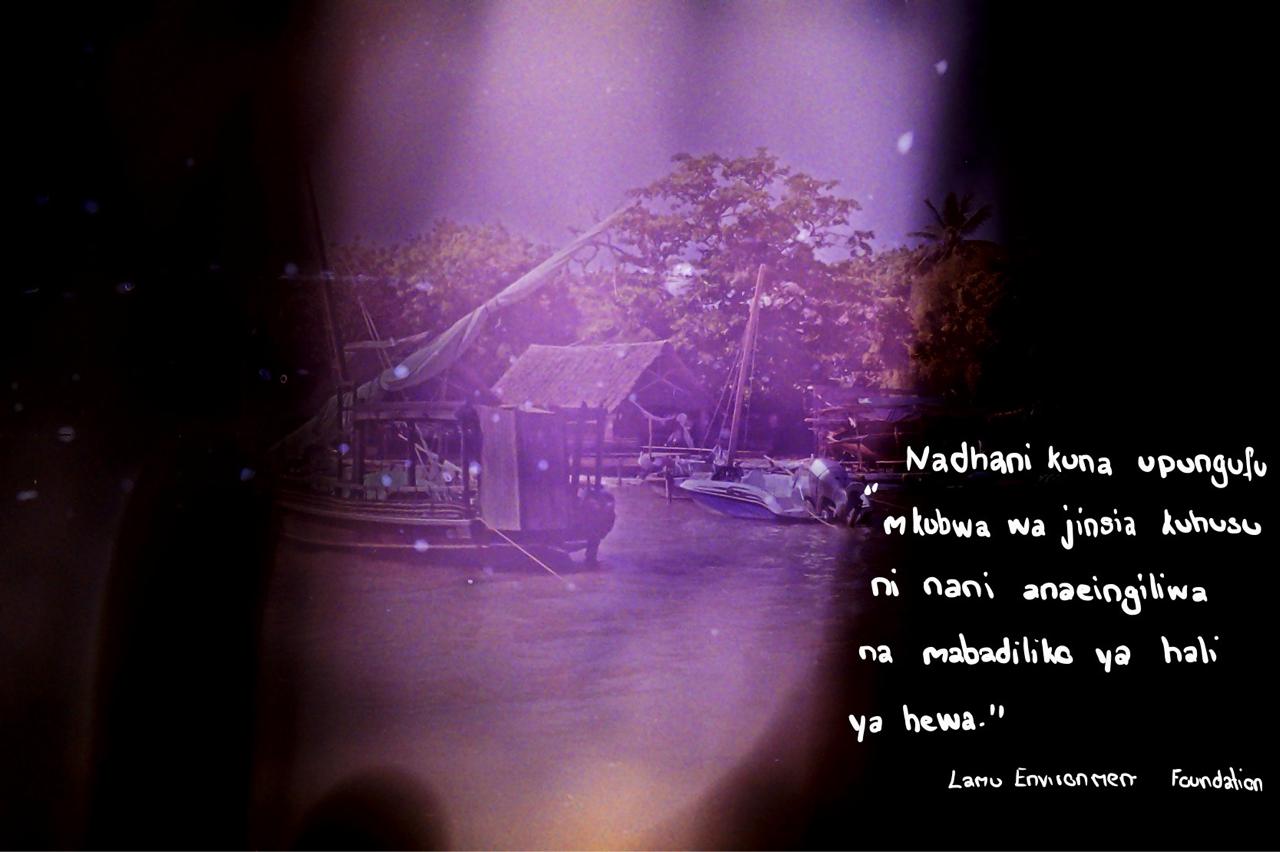

![]()

Local organizations, such as the Lamu Women Alliance, play a vital role in supporting women in overcoming these barriers. They advocate for what they call a “girl code” of solidarity to counter political and social challenges, including harassment and exclusion from decision-making processes. The need for comprehensive educational programs and greater support from both governmental and non-governmental organizations is also highlighted, particularly programs that incorporate indigenous knowledge and are sensitive to local cultural values.

The paper documents that women, who are often responsible for household duties, are more vulnerable during environmental crises. During floods, for example, women’s caregiving roles increase their exposure to danger, limiting their ability to seek safety. Moreover, health risks for women are amplified, as climate change contributes to increased incidences of stillbirths and diseases such as malaria and Zika. The intersection of these issues underscores the urgent need for gender-sensitive policies that recognize the unique vulnerabilities faced by women.

Local organizations, such as the Lamu Women Alliance, play a vital role in supporting women in overcoming these barriers. They advocate for what they call a “girl code” of solidarity to counter political and social challenges, including harassment and exclusion from decision-making processes. The need for comprehensive educational programs and greater support from both governmental and non-governmental organizations is also highlighted, particularly programs that incorporate indigenous knowledge and are sensitive to local cultural values.

The Faza Youth Action Group similarly addresses historical injustices, aiming to amplify marginalized voices and promote equal inclusion. The contributions of these groups emphasize that gender equality is essential for achieving environmental justice in Lamu, where socio-cultural and economic limitations have historically restricted women’s participation in sustainability efforts.

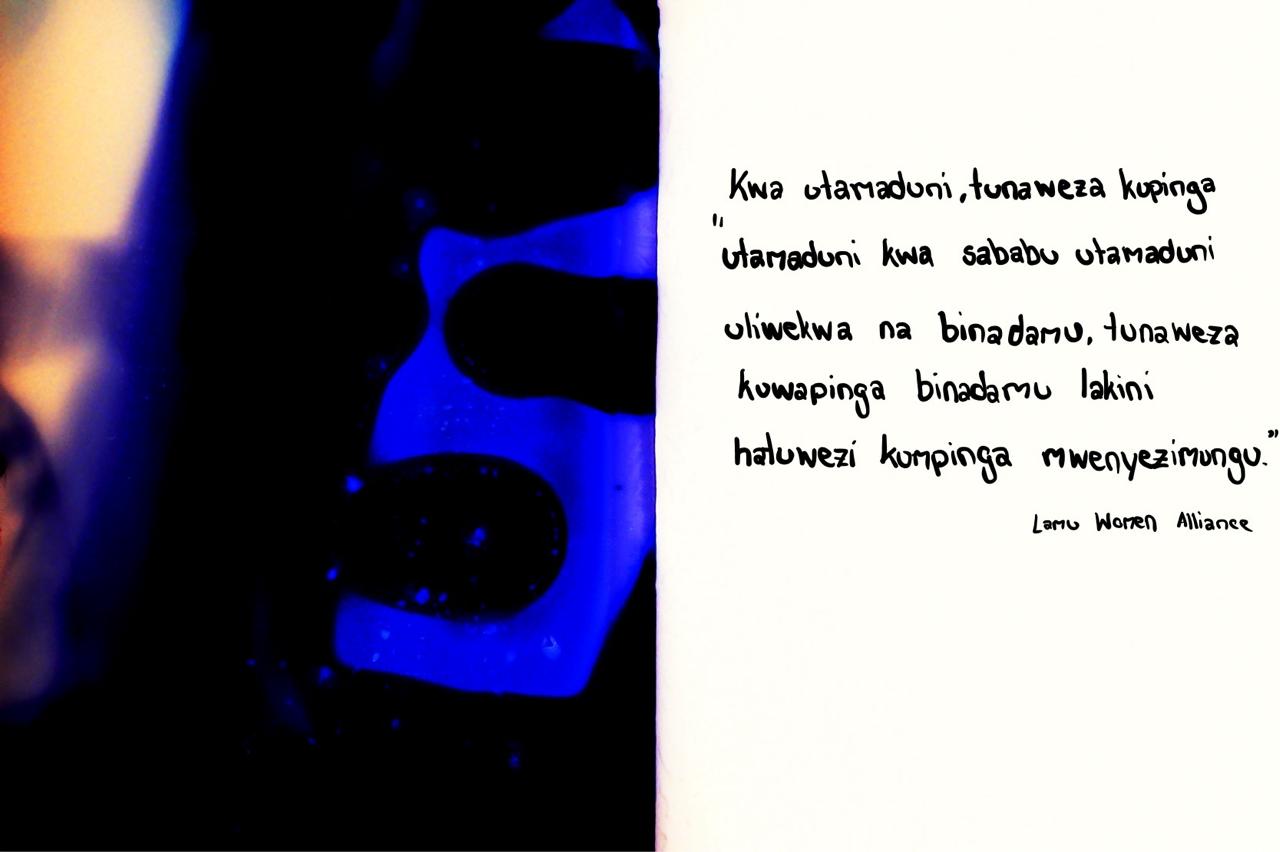

The research explores decolonial and Islamic feminist frameworks to understand how colonial legacies and religious principles influence environmental policies and gender norms in Lamu. Decolonial feminism critiques the enduring effects of colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism, challenging global structures that perpetuate inequality and exploitation. By valuing indigenous knowledge and amplifying marginalized voices, this perspective seeks to dismantle oppressive systems and promote self-determination for women in Lamu.

Islamic feminism, in turn, provides a framework for advancing gender justice within the context of Islamic principles, allowing women to engage in conservation and leadership roles without directly challenging religious beliefs.

For instance, the following statement from an interviewee of the Faza Youth Action Group reflects how women differentially challenge social and religious structures:

The research explores decolonial and Islamic feminist frameworks to understand how colonial legacies and religious principles influence environmental policies and gender norms in Lamu. Decolonial feminism critiques the enduring effects of colonialism, capitalism, and imperialism, challenging global structures that perpetuate inequality and exploitation. By valuing indigenous knowledge and amplifying marginalized voices, this perspective seeks to dismantle oppressive systems and promote self-determination for women in Lamu.

Islamic feminism, in turn, provides a framework for advancing gender justice within the context of Islamic principles, allowing women to engage in conservation and leadership roles without directly challenging religious beliefs.

For instance, the following statement from an interviewee of the Faza Youth Action Group reflects how women differentially challenge social and religious structures:

“We can fight the culture because that was made by humans. We can challenge humans, but we cannot challenge God.”

Initiatives

In addition to these feminist perspectives, this research illustrates how women-led initiatives are essential to sustainable development and social justice. Community projects such as coral reef restoration and octopus closures are examples of how environmental sustainability and economic independence are intertwined. Women in these initiatives challenge traditional gender roles, contributing both financially and socially to their communities while promoting ecological balance. Education is central to these efforts, fostering awareness of environmental issues and reinforcing women’s capacity to advocate for their rights.

The research finds that women’s involvement in Lamu is often defined within cultural contexts; as one member of the Lamu Women Alliance described, empowerment means “changing the way of life to the culture.” Similarly, the Faza Youth Action Group observed that the empowerment process has elevated women’s self-worth and expanded their roles within the community. Such culturally specific understandings of empowerment align with decolonial feminism’s goal to respect local values and resist external influences. The interconnections between gender, religion, and culture thus shape women’s leadership and environmental activism in complex ways.

The research finds that women’s involvement in Lamu is often defined within cultural contexts; as one member of the Lamu Women Alliance described, empowerment means “changing the way of life to the culture.” Similarly, the Faza Youth Action Group observed that the empowerment process has elevated women’s self-worth and expanded their roles within the community. Such culturally specific understandings of empowerment align with decolonial feminism’s goal to respect local values and resist external influences. The interconnections between gender, religion, and culture thus shape women’s leadership and environmental activism in complex ways.

The gendered division of labor and women’s disproportionate vulnerability to climate change highlight the importance of integrating gender perspectives into environmental justice. Community-led aspirations for environmental conservation align with economic activities, enabling women to develop strength and self-sufficiency. However, while women bear many responsibilities in their roles as primary caregivers, they often lack formal recognition and support. Local women’s knowledge, rooted in their cultural heritage and everyday experiences, is invaluable in promoting sustainable practices, as illustrated by their roles in conservation initiatives and traditional fishing practices.

The research emphasizes that sustainability and social justice must go hand in hand, particularly in the context of women’s contributions to environmental conservation in Lamu.

Participants frequently echoed the sentiment that “There is no climate justice without gender justice,” underscoring that sustainability efforts must be inclusive to be effective.

The Lamu Women Alliance advocates for integrating these principles into environmental policies to address gender-specific challenges and ensure women’s participation in leadership roles. The study illustrates that women’s voices are essential to sustainable development.

![]()

The research emphasizes that sustainability and social justice must go hand in hand, particularly in the context of women’s contributions to environmental conservation in Lamu.

Participants frequently echoed the sentiment that “There is no climate justice without gender justice,” underscoring that sustainability efforts must be inclusive to be effective.

The Lamu Women Alliance advocates for integrating these principles into environmental policies to address gender-specific challenges and ensure women’s participation in leadership roles. The study illustrates that women’s voices are essential to sustainable development.

Conclusion

This research underscores the importance of integrating gender justice with environmental sustainability, advocating for policies that support women’s roles in conservation and address the socio-cultural barriers they face. Women’s leadership in Lamu demonstrates the transformative potential of decolonial and ecofeminist frameworks, which challenge global structures of inequality and foreground indigenous knowledge and local empowerment.

These findings illustrate that achieving environmental justice requires acknowledging and addressing gendered inequalities, recognizing women as key contributors to environmental preservation and community resilience.

Through their collective efforts, women in Lamu not only contribute to the local ecosystem but also foster a more equitable and sustainable future for their community.

This research offers valuable insights for policymakers, highlighting the need for inclusive approaches to environmental justice that respect cultural identities and promote gender equity within sustainability practices.

Mama na Bahari #2407

This research project examines the role of women in the fishing industry on Lamu Island, Kenya, where men typically dominate the field. Women primarily engage in fish processing and, in some cases, specialize in octopus fishing.

This project explores how these women navigate traditional boundaries, how cultural expectations shape their participation, and the socio-economic impacts of their contributions.

Their involvement challenges traditional gender norms within the culturally conservative, Muslim-majority society of Lamu.

This project explores how these women navigate traditional boundaries, how cultural expectations shape their participation, and the socio-economic impacts of their contributions.

Context and objectives

The fishing industry in Lamu is vital to the community. Fishing is traditionally seen as men’s work, particularly deep-sea fishing, which is physically demanding and requires specialized skills.

Women’s participation has been largely restricted to shore-based activities like fish processing, trading, and small-scale, near-shore fishing, such as octopus harvesting. This gendered division reflects deep-rooted cultural norms and Islamic teachings, which influence gender roles in Lamu.

Women’s participation has been largely restricted to shore-based activities like fish processing, trading, and small-scale, near-shore fishing, such as octopus harvesting. This gendered division reflects deep-rooted cultural norms and Islamic teachings, which influence gender roles in Lamu.

My central research question is: “What factors and societal values influence women’s participation in the fishing industry in Lamu?”

The study’s objectives include understanding the cultural and religious norms that shape women’s work, examining the challenges they face, and assessing their economic contributions to their communities.

![]()

Findings

The findings reveal that women in Lamu’s fishing industry operate within a framework heavily influenced by cultural and religious expectations. Women’s roles remain largely tied to household responsibilities and shore-based fish processing, a key activity known locally as Mama Karanga, which aligns with conservative Islamic perspectives that assign distinct responsibilities to each gender. Furthermore, in certain areas, especially octopus fishing, women fish independently, staying closer to shore and working among themselves. The economic importance of octopus fishing has led some community elders to accept women’s involvement due to the financial benefits it brings.

Women’s involvement in the fishing industry is influenced by economic necessity, particularly due to limited employment options on the island. The fishing industry however, faces significant economic and environmental challenges. Inadequate infrastructure, like the lack of cold storage facilities, complicates fish preservation and affects women’s incomes.

Environmental issues, including the LAPSSET project, have also impacted fish availability, with pollution and changing marine conditions reducing catches and creating additional economic pressures on women.

Empowerment, as perceived by these women, is nuanced and community-oriented. Through initiatives led by organizations, women receive training and access to resources.

![]()

Women’s involvement in the fishing industry is influenced by economic necessity, particularly due to limited employment options on the island. The fishing industry however, faces significant economic and environmental challenges. Inadequate infrastructure, like the lack of cold storage facilities, complicates fish preservation and affects women’s incomes.

Environmental issues, including the LAPSSET project, have also impacted fish availability, with pollution and changing marine conditions reducing catches and creating additional economic pressures on women.

Empowerment, as perceived by these women, is nuanced and community-oriented. Through initiatives led by organizations, women receive training and access to resources.

Many interviewees expressed a sense of agency from their work, noting that financial independence helps them support their families and contribute to the community.

Empowerment is evident in the women’s ability to make household decisions and engage in collective action to address community issues, such as marine conservation.

Despite the influence of Western perspectives on empowerment, the local women’s concept is rooted in Nego-feminism (Nnaemeka 2004), a form of African feminism that emphasizes negotiation and harmony rather than confrontation. For example, many women continue to balance their fishing activities with traditional roles, such as caring for children and managing household duties, in line with conservative expectations. Women like Mama Pweza, an octopus fisherwoman, embody this approach by working in groups, thus respecting cultural norms about gender-appropriate activities while still advancing economically.

At the same time however, women’s increasing visibility and agency create tensions within the community, particularly regarding traditional expectations.

Some men and elders disapprove of women’s involvement in fishing, fearing it disrupts social structures.

It is said:

“wazee wanasema wanawake wamekuwa kichwa ngumu”, which means “Elders say women have become stubborn”.

However, the acceptance of economically beneficial activities, like octopus fishing, shows that traditional norms in Lamu can be flexible when financial incentives are evident.

Conclusion

This study illustrates how women in Lamu balance economic empowerment with traditional roles, navigating a complex social landscape shaped by cultural norms and economic necessity.

They leverage resources and opportunities within the framework of Islamic gender norms, achieving a form of empowerment that aligns with African feminist ideals of collective welfare.

Although women face significant challenges, they contribute substantially to their families and communities by adapting traditional roles to new economic contexts.

This research underscores the need for culturally sensitive empowerment initiatives that respect local customs while providing meaningful support. Ultimately, the women of Lamu are redefining empowerment on their terms, blending traditional values with economic strengths in ways that contribute positively to their community’s socio-economic and environmental sustainability.

Ways of Living with the Lamu Archipelago

Today the Lamu Archipelago is undergoing a period of change, where land and sea converge under the influence of local and global forces.

These transformations affect the ways in which the community live with their near environment, as well as more distant surroundings in various ways.

Our research aims to capture this evolving landscape through a blend of voices and perspectives, highlighting key themes:

Each perspective reflect the Lamu’s ongoing dialogue, rooted in both tradition and adaptation, as it faces environmental, social, and economic changes.

Our research aims to capture this evolving landscape through a blend of voices and perspectives, highlighting key themes:

- Promises and Pitfalls of the Blue Economy;

- Changing Performance of Fisheries in Amu;

- Experience and Sense-Making of Climate Change;

- Relations to Nature in Times of Crisis;

- Archipelagic Stories of Spirituality; and

- Managed Mangroves.

Each perspective reflect the Lamu’s ongoing dialogue, rooted in both tradition and adaptation, as it faces environmental, social, and economic changes.

Authors

Leo Witzig

Lilian Salama

Lion Tautz

Clara Alder Juul

Rukia Issa

Runzhu Qian

Projects

Ways of Living #2402

“I can read dua in Lamu and cure you in Dubai”: On the Transoceanic Circulation of Spirits

This proejct reflects on how spirituality circulates through spaces in Lamu, and what spiritual practices tell us about the islands’ transoceanic ties to other ports cities in the Indian Ocean.

“I can read dua in Lamu and cure you in Dubai,” Hashid told me one evening during my fieldwork in Lamu, after explaining the various methods he uses as a healer (mtabibu), to cure people of being overcome by spiritual forces (Field notes 25.04.2024).

We sit in the living room of his home in Lamu Old Town. The room offers a tranquil and undisturbed space for our conversation, with the exemption of his two-year-old daughter, who at times seems fairly displeased that I take up her father’s attention. Despite her young age, it occurs to me that she is somehow aware of her father’s expertise, and conscious that I, a complete stranger, have come to her home to learn.

The general term for a spiritual force in Lamu is jinn (jinns or majinni in plural). There exist good and bad jinns. The good jinns do not disturb humans, while it is believed that the bad jinns bring all sorts of misfortune to people. The process of being “taken over” or “put out of control” by a spiritual force is conceived as spirit possession or dispossession. This is where Hashid’s profound knowledge of spirituality is most evident, as he has the ability to free people from spirit possession. As a mtabibu, he carries a jinn, that together with his religious faith, serves as a guiding force in his treatments:

“I have religion in one hand, and the jinn in the other” he states, and hands me his medical license issued by the social services.

Due to Lamu’s maritime connections to other nations in the Indian Ocean, the advent of Islam has led to an enduring influence on the cultural history of the port city. This research presents a study of spirituality on Lamu Island through a relational lens. For this, I ask the following questions: How does spirituality circulate through spaces in Lamu and across geographies? And how are we as urban scholars to squeeze meaning out of these practices?

Reducing spiritual practices to fears or explanatory rationales dismisses their depth and embeddedness in Lamu society, and the ways in which people relate to other urban sites in the Indian Ocean through spirituality.

I consider relationality the starting point of connections across space and situate Lamu at the nexus of studies on spirituality (Larsen 2009, 2014; Ballarin 2009; Giles 2018; Uimonen & Masimbi 2021) and urban maritime literature (Menon et al. 2022, Mahajan 2022, Lavery & Hofmeyr 2020 Pugh 2013, Glissant 1997) to show how spirituality in Lamu creates an archipelagic space of connections between distant urban locales, that are both geographical, bodily, and more-than-material.

The first part of my study delves into the link between spirituality, water, and people, and shows how my interlocutors embody the island’s history of connectedness through spiritual practices around water (Meier 2017; Kosgei 2021). Interactions with tides reveal a deep spiritual connection to the sea, where tidal movements are seen as sacred and imbued with cleansing powers.

“I can read dua in Lamu and cure you in Dubai,” Hashid told me one evening during my fieldwork in Lamu, after explaining the various methods he uses as a healer (mtabibu), to cure people of being overcome by spiritual forces (Field notes 25.04.2024).

We sit in the living room of his home in Lamu Old Town. The room offers a tranquil and undisturbed space for our conversation, with the exemption of his two-year-old daughter, who at times seems fairly displeased that I take up her father’s attention. Despite her young age, it occurs to me that she is somehow aware of her father’s expertise, and conscious that I, a complete stranger, have come to her home to learn.

The general term for a spiritual force in Lamu is jinn (jinns or majinni in plural). There exist good and bad jinns. The good jinns do not disturb humans, while it is believed that the bad jinns bring all sorts of misfortune to people. The process of being “taken over” or “put out of control” by a spiritual force is conceived as spirit possession or dispossession. This is where Hashid’s profound knowledge of spirituality is most evident, as he has the ability to free people from spirit possession. As a mtabibu, he carries a jinn, that together with his religious faith, serves as a guiding force in his treatments:

“I have religion in one hand, and the jinn in the other” he states, and hands me his medical license issued by the social services.

Due to Lamu’s maritime connections to other nations in the Indian Ocean, the advent of Islam has led to an enduring influence on the cultural history of the port city. This research presents a study of spirituality on Lamu Island through a relational lens. For this, I ask the following questions: How does spirituality circulate through spaces in Lamu and across geographies? And how are we as urban scholars to squeeze meaning out of these practices?

Reducing spiritual practices to fears or explanatory rationales dismisses their depth and embeddedness in Lamu society, and the ways in which people relate to other urban sites in the Indian Ocean through spirituality.

I consider relationality the starting point of connections across space and situate Lamu at the nexus of studies on spirituality (Larsen 2009, 2014; Ballarin 2009; Giles 2018; Uimonen & Masimbi 2021) and urban maritime literature (Menon et al. 2022, Mahajan 2022, Lavery & Hofmeyr 2020 Pugh 2013, Glissant 1997) to show how spirituality in Lamu creates an archipelagic space of connections between distant urban locales, that are both geographical, bodily, and more-than-material.

The first part of my study delves into the link between spirituality, water, and people, and shows how my interlocutors embody the island’s history of connectedness through spiritual practices around water (Meier 2017; Kosgei 2021). Interactions with tides reveal a deep spiritual connection to the sea, where tidal movements are seen as sacred and imbued with cleansing powers.

Through rituals, Hashid uses the ebbs and flows as a medium to engage with spirits, invoking prayers to channel divine forces of the sea for protection and healing. Hashid’s practices connect him to a broader cultural and historical tapestry, reflecting an embodied spiritual relationship that links Lamu to other Indian Ocean communities.

After converging around the watery quality of spirituality in Lamu, I extend the analysis to a focus on the fringe between water and land as being a specifically dense spiritual space (Mahajan 2022; Kucher 1995).

After converging around the watery quality of spirituality in Lamu, I extend the analysis to a focus on the fringe between water and land as being a specifically dense spiritual space (Mahajan 2022; Kucher 1995). My interlocutor Yunus’ memory of a spirit encounter near the main jetty of Lamu Old Town highlights the jetty’s unique role as a liminal space, where the boundary between water and land holds spiritual intensity and guides social behaviour. The materiality and the social relations played out around the jetty-space extends Mahajan’s concept of "archipelagic relationality".

The second part of my study explores the translocal nature of jinns in Lamu, and challenges the dichotomy between human and spiritual identities, suggesting a more integrated and archipelagic relationship between the worlds. Hasid’s recalling of his friend Issa’s possession by a Russian-speaking jinn exemplifies Ensing Ho's (2006) concept of "local cosmopolitanism.” I argue that this concept extends into the spiritual realm, where jinns also embody the junctures of local and global influences, which offers a critique of Larsen’s argument (2024) that the spiritual and human world are considered separate, though they are intertwined. I rather propose that spirituality in Lamu is regarded an inseparable part of the human world.

The last and third part proposes that modernity offers alternative ways of practicing spirituality in Lamu (Meier 2017). This argument is further deepened by a comment to Dilip Menon’s argument that migration across the oceanic distances creates a scale of its own (Menon et al. 2022: 8). Based on Hashid’s remarks “I can read dua in Lamu, and cure you in Dubai”, I suggest spirituality as a scale of it own.

The last and third part proposes that modernity offers alternative ways of practicing spirituality in Lamu (Meier 2017). This argument is further deepened by a comment to Dilip Menon’s argument that migration across the oceanic distances creates a scale of its own (Menon et al. 2022: 8). Based on Hashid’s remarks (“I can read dua in Lamu, and cure you in Dubai”), I suggest spirituality as a scale of it own.

Spirituality as a scale of its own creates alternative connections between spatial, temporal, emotional and socio- political elements and provides a pathway to think space less as a surface to move on or a scene for cultural practices or beliefs, and more of a medium to think about felt connections.

By exploring the role of jinns on Lamu Island, my study reveals the role of spirituality in Lamu as a means of cultural and historical relationality to the wider Indian Ocean world, where multiple spiritual practices intersect. Together they create an archipelagic space of connections between Lamu and distant urban locals that are both geographical, bodily, and more-than-material, demonstrating that spirituality circulates through numerous spaces in Lamu and across the Indian Ocean as process and result of many relations at a time.

Ways of Living #2403

Mangroves

We were on the boat, the sky was blue and the clouds were white.

I saw a lot of mangroves above the sea, like soldiers protecting the coast. Slowly darkness fell, and the forest became as silent as the dark night.

They are so mysterious, beautiful, and reliable, and it is said that elves live in them. I don’t want to talk about elves here. I want to consider their future.

Mangroves, which are a natural and cultural element of heritage in Lamu, have received a lot of attention due to the industrialization and urbanization of Lamu. Many institutions are trying to protect and restore them, such as the KFS (Kenya Forest Service), CFAs (Community Forest Associations), NGOs, and local communities.

I saw a lot of mangroves above the sea, like soldiers protecting the coast. Slowly darkness fell, and the forest became as silent as the dark night.

They are so mysterious, beautiful, and reliable, and it is said that elves live in them. I don’t want to talk about elves here. I want to consider their future.

Mangroves, which are a natural and cultural element of heritage in Lamu, have received a lot of attention due to the industrialization and urbanization of Lamu. Many institutions are trying to protect and restore them, such as the KFS (Kenya Forest Service), CFAs (Community Forest Associations), NGOs, and local communities.

What is the relationship between these institutions? What is the relationship between mangroves and local people? And are mangroves effectively protected?

This project focuses on the relationship between mangrove conservation groups, people, and mangroves themselves. The aim is to answer the following question: What kind of restoration method can better ensure that mangroves are effectively passed on to future generations as natural and cultural heritage?

If we still have a little compassion for the remaining species, if we really put ourselves in the middle of them, we will understand that animals and plants are as alive as humans.

Based on existing research and inspired by Calkins’ “empathy with plants”(2020), this project has preliminarily and poetically explored which of the several existing restoration methods is more conducive to restoring the mangroves themselves and restoring people’s relationship with them.

If we still have a little compassion for the remaining species, if we really put ourselves in the middle of them, we will understand that animals and plants are as alive as humans.

Based on existing research and inspired by Calkins’ “empathy with plants”(2020), this project has preliminarily and poetically explored which of the several existing restoration methods is more conducive to restoring the mangroves themselves and restoring people’s relationship with them.

Lifestyle

Work at sunrise and rest at sunset.

People pray, people sing.

The boat drifting with the sea,

The starry sky in sight.

Houses in the distance,

Waves close by,

Chatty backpackers.

All tell the stories...

People pray, people sing.

Children and donkeys are crying

from time by time.

However, you do not feel noisy at all,

You feel that, this is life itself.

The boat drifting with the sea,The starry sky in sight.

Houses in the distance,

Waves close by,

Chatty backpackers.

All tell the stories...

Forest and sea

If the forest is the habitat of the soul,

then the sea is the home of the wanderer.

Rare seabirds were low in the sky,

The moon showing half its face.

The clouds are like the white breasts of swans,

People running, laughing and crying.

Day after day, year after year,

Until the end of the world...

Sometimes, the darkness

extinguished the light of the clouds,

Just like the distant dreams.

Lonely old people,

Lost middle-aged people,

And the little ones,

Who do not know what they are doing...

Ways of Living #2404

Complexity and Contradiction in Ecology

“Will we allow anthrax or cholera microbes to attain self-realization in wiping out sheep herds or human kindergartens? Will we continue to deny salmonella or botulism micro-organisms their equal rights when we process the dead carcasses of animal and plants that we eat?”

(Chakrabarty 2021, 194)We meet in Hassan’s office on the first floor. Hassan is a community organizer, and he has arranged for us to speak with an Ustadh, a Muslim teacher and leader. My co-researcher has asked Hassan to set up the interview, and she has invited me to come along. Lamu is a majority Muslim community and before the Ustadh arrives, we chat with Hassan about the rules of Islam regarding the treatment of animals. The Ustadh, a man around 30 years old wearing a football jersey, feels most comfortable speaking in Kiswahili, so Hassan has volunteered to translate. Throughout, he also offers his own opinions at various points.

In the second half of the interview, after my co-researcher has asked her questions, we return to the topic of animals in Islam. The Ustadh explains that while the elders still follow the rules of the Qu’ran, younger people have lost their way and treat animals — from donkeys to ants — poorly. I ask if the rules extend to fish and Hassan takes a moment to explain something to me before translating:

“Okay, let me tell you something. In the sea, Islamically, everything that comes from the sea is edible.”

The Ustadh’s response is similar: “In the sea, there is no mistreatmeant. Because they're going there for fish, and fish is a meal. People will eat it, right?”

In Lamu, a historically seafaring town on the shores of the Indian Ocean, “70 percent of the local population depends on artisanal fishing.” (Lesutis 2022, p. 2438) A hierarchy of beings begins to emerge, with (differentiated) humans on top and a value-gradient of animals below. What seems at first glance to be an instance of the double fracture laid out by Malcom Ferdinand in his book Decolonial Ecology is quickly qualified by the Ustadh: “In a killing of this animal or insect, there is a way of killing. Like, for instance, we cannot kill a mosquito for consumption, right? But it's just for prevention. Because if you don't take care, we'll get malaria.” Malaria is a serious illness and can be fatal — fracture or not, preventive action is necessary for health and survival.

Still, I cannot shake the feeling that we have very different concepts of equality. Hassan explains that “we have rights, and animals have rights. So, it's equal. For Islam, it's very equal. You're not supposed to kill it without a reason. If you have a reason, you do it. […] That is Islam.” As a conscientious vegan, I want to think there is never a reason to kill a human or any other animal. One might reasonably ask what makes my drawing of the line between justified and condemnable in between plants and animals more valid than Hassan’s at the border in between animals and humans; I leave it to you, the reader, to consider this ethical quandary. No matter which version of equality you settle on, though, the Ustadh acknowledges that that is not how things are anyways:

Still, I cannot shake the feeling that we have very different concepts of equality. Hassan explains that “we have rights, and animals have rights. So, it's equal. For Islam, it's very equal. You're not supposed to kill it without a reason. If you have a reason, you do it. […] That is Islam.” As a conscientious vegan, I want to think there is never a reason to kill a human or any other animal. One might reasonably ask what makes my drawing of the line between justified and condemnable in between plants and animals more valid than Hassan’s at the border in between animals and humans; I leave it to you, the reader, to consider this ethical quandary. No matter which version of equality you settle on, though, the Ustadh acknowledges that that is not how things are anyways:

“We need to have equal rights for everything. But it is not practiced. It is only practiced to the direct benefit. […] Things are done for productivity. So, if something is not productive to me, I don't care about it. But there is a need for everything to be treated equally.”

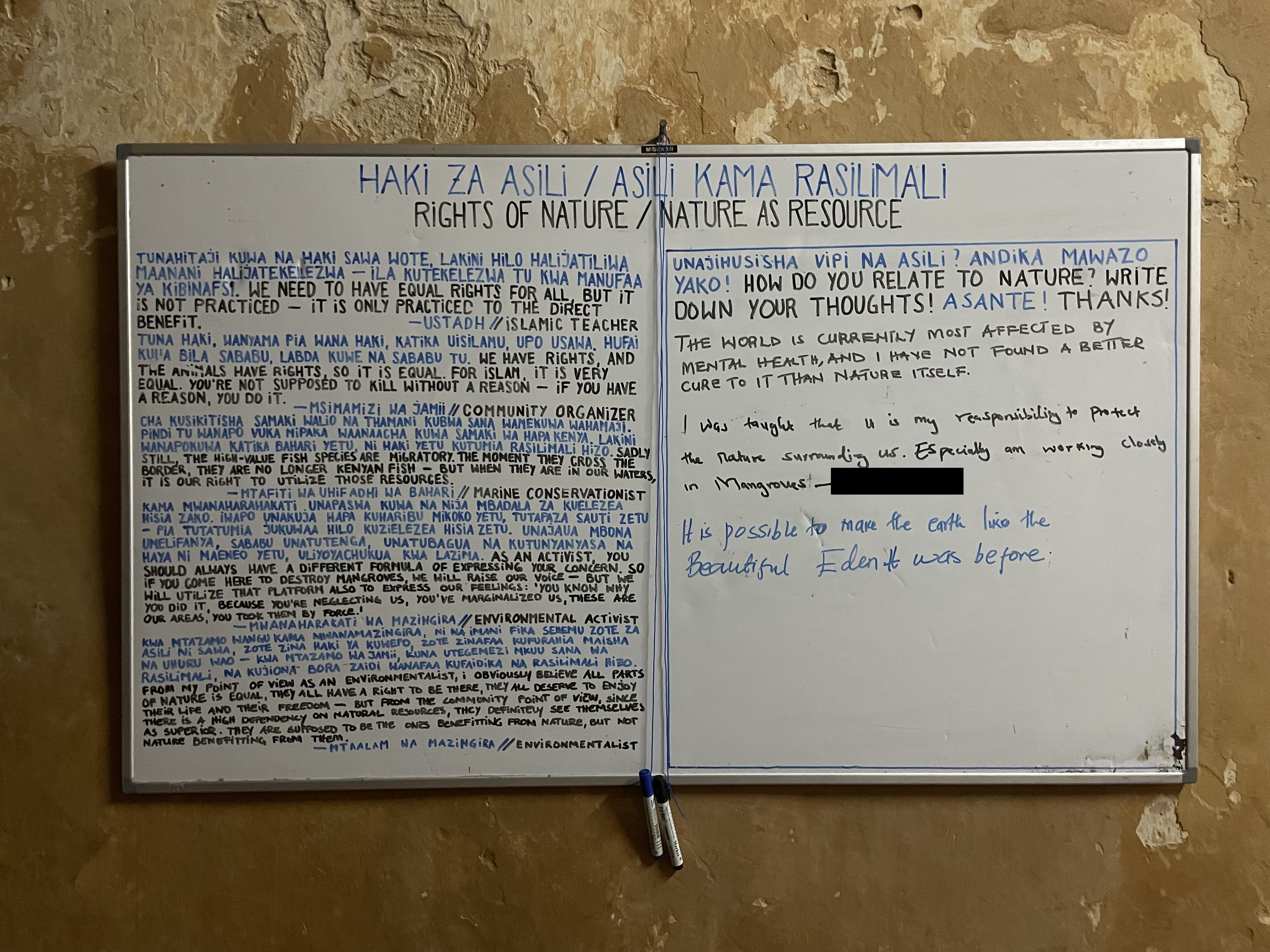

Haki Za Asili // Asili Kama Rasilmali

Rights Of Nature // Nature As Resource

Tunahitaji kuwa na haki sawa wote, lakini hilo halijatiliwa maanani, halijatekelezwa -ila kutekelezwa tu Kwa manufaa ya kibinafsi.

We need to have equal rights for all, but it’s not practiced — it’s only practiced to the direct benefit.

Tuna haki, wanyama pia Wana haki, Katika uisilamu, upo usawa. Hufai kuua bila sababu, labda kuwe na sababu tu.

We have rights, and the animals have rights, so it is equal. For Islam, it is very equal. You’re not supposed to kill without a reason — if you have a reason, you do it.

Cha kusikitisha samaki walio na thamani kubwa sana wamekuwa wahamaji. Pindi tu wanapo vuka mipaka waanaacha kuwa samaki wa hapa Kenya. Lakini wanapokuwa katika bahari yetu, ni haki yetu kutumia rasilimali hizo.

We need to have equal rights for all, but it’s not practiced — it’s only practiced to the direct benefit.

— Ustadh / Islamic Teacher

Tuna haki, wanyama pia Wana haki, Katika uisilamu, upo usawa. Hufai kuua bila sababu, labda kuwe na sababu tu.

We have rights, and the animals have rights, so it is equal. For Islam, it is very equal. You’re not supposed to kill without a reason — if you have a reason, you do it.

— Msimamizi wa Jamii / Community Organizer

Cha kusikitisha samaki walio na thamani kubwa sana wamekuwa wahamaji. Pindi tu wanapo vuka mipaka waanaacha kuwa samaki wa hapa Kenya. Lakini wanapokuwa katika bahari yetu, ni haki yetu kutumia rasilimali hizo.

Sadly still, the high-value fish species are migratory. The moment they cross the border, they are no longer Kenyan fish — but when they are in our waters, it is our right to utilize those resources.

— Mtafiti wa Uhifadhi wa Bahari / Marine Conservationist

Kama mwanaharahakati unapaswa kuwa na njia mbadala za kuelezea hisia zako. Iwapo unakuja hapa kuharibu Mikoko yetu, tutapaza sauti zetu — Pia tutatumia jukuwaa Hilo kuzielezea hisia zetu. Unajaua mbona umelifanya, sababu unatutenga, unatubagua na kutunyanyasa na haya ni maeneo yetu,uliyoyachukua kwa lazima.

As an activist, you should always have a different formula of expressing your concern. So if you come here to destroy mangroves, we will raise our voice — but we will utilize that platform also to express our feelings: ‘You know why you did it, because you’re neglecting us, you’ve marginalized us, these are our areas, you took them by force.’

— Mwanaharakati wa Mazingira / Environmental Activist

Kwa mtazamo wangu kama mwanamazingira, Ni na Imani fika sehemu zote za asili ni sawa,zote zina haki ya kuwepo, zote zinafaa kufurahia maisha na uhuru wao — Kwa mtazamo wa jamii, Kuna utegemezi mkuu sana wa rasilimali, na kujiona bora zaidi wanafaa kufaidika na rasilimali hizo .

From my point of view as an environmentalist, I obviously believe all parts of nature is equal, they all have a right to be there, they all deserve to enjoy their life and their freedom — but from the community point of view, since there is a high dependency on natural resources, they definitely see themselves as superior. They are supposed to be the ones benefitting from nature, but not nature benefitting from them.

As an activist, you should always have a different formula of expressing your concern. So if you come here to destroy mangroves, we will raise our voice — but we will utilize that platform also to express our feelings: ‘You know why you did it, because you’re neglecting us, you’ve marginalized us, these are our areas, you took them by force.’

— Mwanaharakati wa Mazingira / Environmental Activist

Kwa mtazamo wangu kama mwanamazingira, Ni na Imani fika sehemu zote za asili ni sawa,zote zina haki ya kuwepo, zote zinafaa kufurahia maisha na uhuru wao — Kwa mtazamo wa jamii, Kuna utegemezi mkuu sana wa rasilimali, na kujiona bora zaidi wanafaa kufaidika na rasilimali hizo .

From my point of view as an environmentalist, I obviously believe all parts of nature is equal, they all have a right to be there, they all deserve to enjoy their life and their freedom — but from the community point of view, since there is a high dependency on natural resources, they definitely see themselves as superior. They are supposed to be the ones benefitting from nature, but not nature benefitting from them.

— Mtaalam wa Mazingira / Environmentalist

Mvuvi chake ni unga– the fishermen goes with the flour

This Swahili proverb was quoted by a Lamu County executive committee member, who used it to explain the precarious situation of fishermen in Lamu today. According to him, “go with the flour” is translatable to the english proverb living from the hand to the mouth. Although fishing and fishing-related business is one of the main income sources of coastal communities in the Lamu archipelago, many fishers live day to day and with little means. In recent years, they have faced multiple challenges such as rising fuel prices and loss of access to good fishing grounds as a result of LAPSSET, a major regional infrastructure project. The health of fish populations and their ecosystems is under pressure from ocean warming, pollution, and illegal fishing practices, all of which damage the fish population and decrease overall biodiversity.

While this description depicts a challenging situation, it is only a momentary state of a dynamic field. Starting a few years ago, connected through the term Blue Economy, a plethora of programs and policies where initiated, which should help the socioeconomic development of coastal communities while introducing measures to protect life in the ocean. The Kenyan government and external actors such as the World Wildlife Foundation, the World Bank and the European Union are mobilizing the term Blue Economy in their programs with the promise to uplift fishers from poverty, develop the market capacity and meanwhile ensure a better security and environmental protection in the coastal waters.

Research goal

The goal of this research was to understand the interplay of different programs and policies active in Lamu and their related ambitions and challenges.

Therefore I approached the topic from two sides. On the one hand, I studied the context and ambitions of programs which use the term “Blue Economy” and the recent development of governing structures in the Kenyan maritime and costal domain. On the other hand, I conducted interviews with fishermen, NGO workers, and local government representatives in order to learn about the interests, lived experiences, and challenges faced in the implementation of different programs and policies.

Interventions

Current developments in the Blue Economy are heralded by stating their ambitions to help fisherfolk have more stable incomes, to protect the marine environment, and simultaneously increase production.

This should be facilitated by creating alternative income sources for some, while providing others with boats big enough to exploit the fish resources further out in the EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone). Meanwhile, the fisherfolk practicing near coast fishing should participate in the management of the co-managed areas, in which temporary closures allow the fish population to recover.

Co-managed areas are relatively nascent and although often mentioned as a key part of the solution, they are still far from a common sight. Offshore fishing is often spoken of, but so far the Lamu Archipelago lacks the cooling infrastructure to even support the current catch.

Though many plans exist and large sums of funding have been invested, most of the fishermen still go with the flour.

Though many plans exist and large sums of funding have been invested, most of the fishermen still go with the flour.

New Markets

What will come with quite high certainty is a new landing site with cold storage capacities, an adjacent marketplace and processing plant for fish and seafood in Mokowe. This will help to build the aspired deep sea capacity and, thanks to more direct access to the international market, likely increase potential profits. Whether boat owners will stay as intermediaries or whether government initiatives to give the fisherfolk access to sell directly in the market remains to be seen when it is built.

Conflicting with the hope to get the now too numerous fisherfolk to find other occupations, the potential higher incomes enabled through this new market access combined with the scarcity of other job opportunities could have an adverse effect.

Ultimately, while changing the sector might take some time, overfishing and ocean warming induced changes are accelerating. Coral bleaching related to the 2023-2024 El Niño has shown how sensitive the coral ecosystem reacts to temperature changes. On top of that, the environmental impact the further construction and operation of the LAPSSET Port will put additional stress on the ecosystems.

Outlook

Since leaving Lamu in May 2024, compensation for livelihood loss caused by the first part of the LAPSSET Port construction was finally paid, after many years of waiting.

This spurs hopes that fishermen will be able to invest in alternative income sources or their own equipment to reduce the dependencies on boat owners as middle men.

In June 2024, massive protests against the new financial bill, which would have further increased gas prices, have forced President William Ruto to renounce the bill and replace his entire board of ministers. I conducted my research in a moment when many things were changing, on different scales at different speeds. What comes of it remains to be observed in the future.

Ng'amba // Plastic

Through the stories of local residents, our documentary film “Ng'amba: Maji yakishamwagika hayazoleki tena” (Once Water Has Been Spilled, It Cannot Be Recovered) delves into the impacts of plastic waste on the community and its environment.

It highlights the challenges in waste management, the local initiatives for handling plastics such as PET, and the economic inequalities that complicate these efforts. The films aims to raise awareness about the complex, global nature of plastic pollution and its local impact on Lamu island.

Authors

Ahmed Adhan

Ruth Lozi

Nadja Nievergelt

Henning Weiss

Ahmed Adhan

Ruth Lozi

Nadja Nievergelt

Henning Weiss

Projects

What is truly disposable?

This seemingly simple question reveals more than meets the eye. It is a question that relates to what we consider less important, less valuable, and less necessary. It encourages us to reflect on the ease with which we grant both material and immaterial things worthlessness. How is it that we view certain objects and even people as disposable, and what are the wider consequences of this disposability?

In contemporary western discourse there is frequent dialogue surrounding our consumer society, which is tied the desire to purchase new things, use, and then dispose of them, turning these objects into waste (Crocker 2012, 1,2; Goodwin et al. 2008, 1,4). That moment of an object turning into waste is often when the object is considered somebody else’s problem (Crocker 2012, 1). Waste is out of sight and out of mind (Barnes 2019, 1), encapsulated by the NIMBY syndrome meaning “Not in my back yard” (Dalzero 2021, 207). But the question is in whose back yard then? Who must carry the burden of disposability?

Working alongside two members of the Lamu Youth Alliance and a fellow student from the University of Basel, we immersed ourselves in the community's approach to plastic waste and the lives of waste pickers. As we learnt our way through the everyday landscape of discarded materials, the question of what we throw away and why stayed present in my mind during both the research and writing phases of this project. In Lamu, the discarded pieces of plastic felt like a reflection of the cultural, economic, and historical complexity of the island, showing how deeply the concept of disposability is entangled in local and global life.

In contemporary western discourse there is frequent dialogue surrounding our consumer society, which is tied the desire to purchase new things, use, and then dispose of them, turning these objects into waste (Crocker 2012, 1,2; Goodwin et al. 2008, 1,4). That moment of an object turning into waste is often when the object is considered somebody else’s problem (Crocker 2012, 1). Waste is out of sight and out of mind (Barnes 2019, 1), encapsulated by the NIMBY syndrome meaning “Not in my back yard” (Dalzero 2021, 207). But the question is in whose back yard then? Who must carry the burden of disposability?

Working alongside two members of the Lamu Youth Alliance and a fellow student from the University of Basel, we immersed ourselves in the community's approach to plastic waste and the lives of waste pickers. As we learnt our way through the everyday landscape of discarded materials, the question of what we throw away and why stayed present in my mind during both the research and writing phases of this project. In Lamu, the discarded pieces of plastic felt like a reflection of the cultural, economic, and historical complexity of the island, showing how deeply the concept of disposability is entangled in local and global life.

To delve deeper into the topic surrounding waste, particularly plastic waste and waste workers in the context of Lamu, I was inspired by Lucy Bell’s paper “Place, People, and Processes in Waste Theory: A Global South Critique” (Bell 2019). In it she critiques the fact that traditional waste theories predominantly take European and US-centered perspectives that often ignore the realities of the Global South (Ibid, 99-100). These theories usually assume a physical and ideological distance from waste, which is not the case in many communities in the Global South including, from my observations, Lamu (Ibid, 101).

Bell's critique guided me to fulfil her call to understand waste from the perspective of those who live with, on, and beside it (Bell 2019, 98).

Waste is present, it is visible and so are those who work with it.

For countless people in places like Lamu, waste is an immediate, everyday presence that affects and shapes their lives in profound ways.

Bell's critique guided me to fulfil her call to understand waste from the perspective of those who live with, on, and beside it (Bell 2019, 98).

Plastic boys

During our research, I found the story of a local plastic waste collector, Jassim, whose daily work is often stigmatized and overlooked, particularly touching (Issa Interview 2024). We shadowed Jassim in Lamu's newly built India quarter, where he gathers waste for pickup by Flipflopi, a local waste management group. India, unlike the well-kept parts of Lamu Town, relies heavily on local waste pickers like Jassim. As we began our interview, a group of young men laughingly called out to him “Rastaman”, a term which then characterized the conversation we were about to begin.

Jassim shared insights that reveal not only his daily and economic struggles, but also the broader societal attitudes towards his waste work and subsequent marginalization and stigmatization:

“Young people feel ashamed to collect these things; they feel embarrassed to be seen collecting these things; they feel they look like me”,

he remarked, his voice steady, but reflecting the burden of the societal scrutiny he is regularly facing[ML1] . Derogatory remarks like “Rastaman is crazy” further illustrate a belief system that equates waste collecting with madness or failure, ignoring its environmental significance and its societal value. In areas on Lamu’s outskirts, where no governmental waste workers are present (Lee Fieldnotes 2024a), Jassim’s role is vital yet stigmatized. This reflects a broader prejudice towards certain types of labor also seen globally, where waste work is often labeled as “dirty” or “impoverished”, the work of those who “lack economic resources” or “prospects”, closely associated with the waste they collect or even equated with the waste itself (Kornberg 2020, 148; Vázquez 2016, 127; Porras Bulla, Rendon, and Espluga Trenc 2021, 1303).

Jassim’s story raises important questions about the wider implications of waste, disposability, and invisibility.

Jassim shared insights that reveal not only his daily and economic struggles, but also the broader societal attitudes towards his waste work and subsequent marginalization and stigmatization:

“Young people feel ashamed to collect these things; they feel embarrassed to be seen collecting these things; they feel they look like me”,

he remarked, his voice steady, but reflecting the burden of the societal scrutiny he is regularly facing[ML1] . Derogatory remarks like “Rastaman is crazy” further illustrate a belief system that equates waste collecting with madness or failure, ignoring its environmental significance and its societal value. In areas on Lamu’s outskirts, where no governmental waste workers are present (Lee Fieldnotes 2024a), Jassim’s role is vital yet stigmatized. This reflects a broader prejudice towards certain types of labor also seen globally, where waste work is often labeled as “dirty” or “impoverished”, the work of those who “lack economic resources” or “prospects”, closely associated with the waste they collect or even equated with the waste itself (Kornberg 2020, 148; Vázquez 2016, 127; Porras Bulla, Rendon, and Espluga Trenc 2021, 1303).

Jassim’s story raises important questions about the wider implications of waste, disposability, and invisibility.

The stigma associated with what is often viewed as “dirty work” is not only physical, but also societal and moral, deeply impacting those who manage waste (Meiu 2020, 225-26). Meiu’s analysis highlights how plastic boys are marginalized not just for their economic status but also for handling the foreign and culturally degrading plastic objects.

This exploration into the lives of various waste workers in Lamu not only highlights the stigmatization they face, but also forces us to acknowledge and recognize their essential but overlooked contribution to our daily lives and the wellbeing of our environment. It prompts us to re-examine our notions of what constitutes valuable labor and challenges the origins of these ideas. By examining how waste is viewed as disposable, we see a parallel to how people who work with waste are similarly viewed as tainted by their association with the objects they handle. However, this stigma seems to vary depending on the context, history, and type of waste handled, suggesting that the stigma attached to waste work is not uniform, but is influenced by these factors.

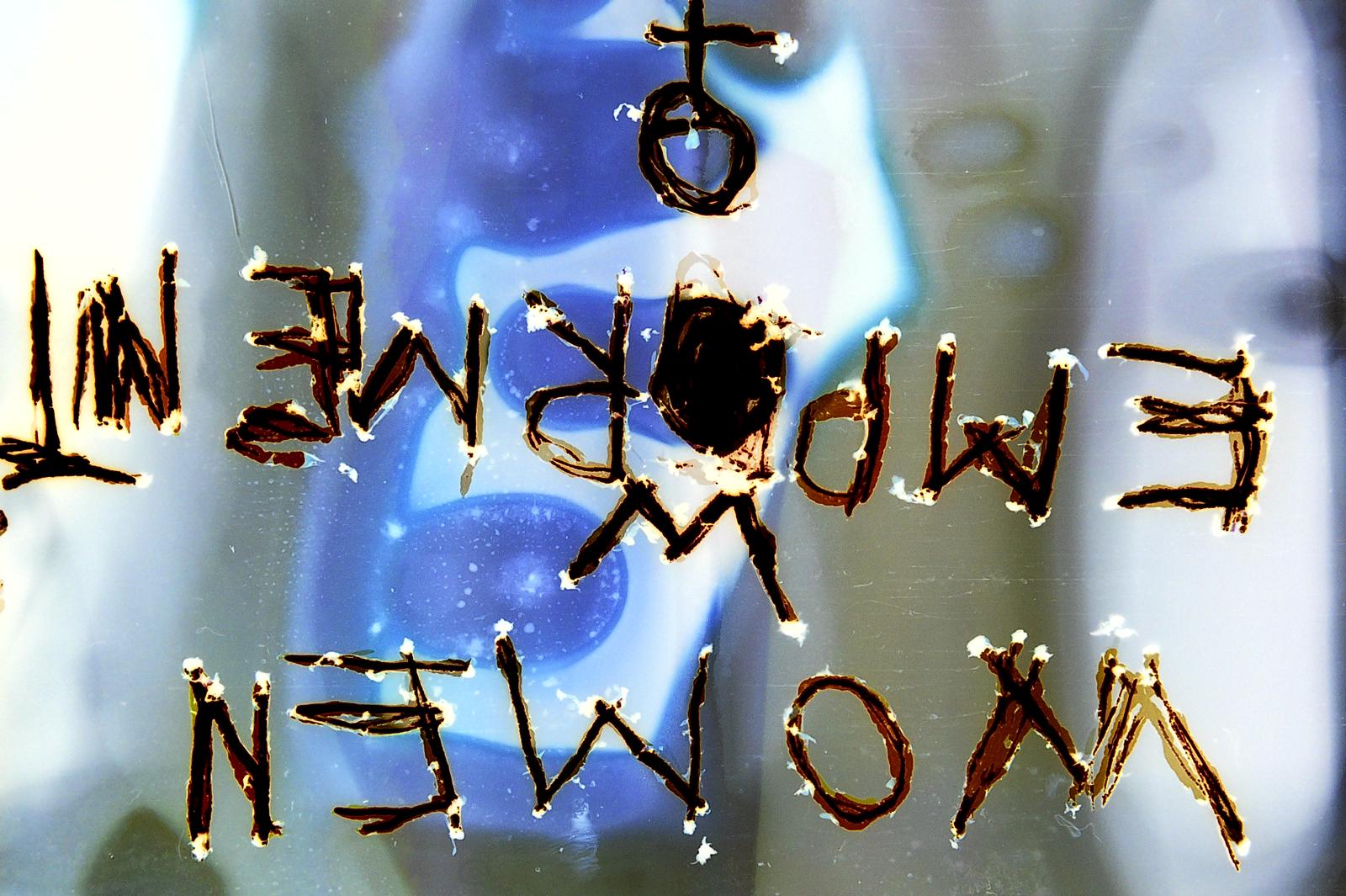

![]()

Both plastic boys and waste workers, through their association with plastic, confront judgments tied to the broader implications of disposability and societal invisibility.

This exploration into the lives of various waste workers in Lamu not only highlights the stigmatization they face, but also forces us to acknowledge and recognize their essential but overlooked contribution to our daily lives and the wellbeing of our environment. It prompts us to re-examine our notions of what constitutes valuable labor and challenges the origins of these ideas. By examining how waste is viewed as disposable, we see a parallel to how people who work with waste are similarly viewed as tainted by their association with the objects they handle. However, this stigma seems to vary depending on the context, history, and type of waste handled, suggesting that the stigma attached to waste work is not uniform, but is influenced by these factors.