Ways of Living with the Lamu Archipelago

Today the Lamu Archipelago is undergoing a period of change, where land and sea converge under the influence of local and global forces.

These transformations affect the ways in which the community live with their near environment, as well as more distant surroundings in various ways.

Our research aims to capture this evolving landscape through a blend of voices and perspectives, highlighting key themes:

Each perspective reflect the Lamu’s ongoing dialogue, rooted in both tradition and adaptation, as it faces environmental, social, and economic changes.

Our research aims to capture this evolving landscape through a blend of voices and perspectives, highlighting key themes:

- Promises and Pitfalls of the Blue Economy;

- Changing Performance of Fisheries in Amu;

- Experience and Sense-Making of Climate Change;

- Relations to Nature in Times of Crisis;

- Archipelagic Stories of Spirituality; and

- Managed Mangroves.

Each perspective reflect the Lamu’s ongoing dialogue, rooted in both tradition and adaptation, as it faces environmental, social, and economic changes.

Authors

Leo Witzig

Lilian Salama

Lion Tautz

Clara Alder Juul

Rukia Issa

Runzhu Qian

Projects

Ways of Living #2402

“I can read dua in Lamu and cure you in Dubai”: On the Transoceanic Circulation of Spirits

This proejct reflects on how spirituality circulates through spaces in Lamu, and what spiritual practices tell us about the islands’ transoceanic ties to other ports cities in the Indian Ocean.

“I can read dua in Lamu and cure you in Dubai,” Hashid told me one evening during my fieldwork in Lamu, after explaining the various methods he uses as a healer (mtabibu), to cure people of being overcome by spiritual forces (Field notes 25.04.2024).

We sit in the living room of his home in Lamu Old Town. The room offers a tranquil and undisturbed space for our conversation, with the exemption of his two-year-old daughter, who at times seems fairly displeased that I take up her father’s attention. Despite her young age, it occurs to me that she is somehow aware of her father’s expertise, and conscious that I, a complete stranger, have come to her home to learn.

The general term for a spiritual force in Lamu is jinn (jinns or majinni in plural). There exist good and bad jinns. The good jinns do not disturb humans, while it is believed that the bad jinns bring all sorts of misfortune to people. The process of being “taken over” or “put out of control” by a spiritual force is conceived as spirit possession or dispossession. This is where Hashid’s profound knowledge of spirituality is most evident, as he has the ability to free people from spirit possession. As a mtabibu, he carries a jinn, that together with his religious faith, serves as a guiding force in his treatments:

“I have religion in one hand, and the jinn in the other” he states, and hands me his medical license issued by the social services.

Due to Lamu’s maritime connections to other nations in the Indian Ocean, the advent of Islam has led to an enduring influence on the cultural history of the port city. This research presents a study of spirituality on Lamu Island through a relational lens. For this, I ask the following questions: How does spirituality circulate through spaces in Lamu and across geographies? And how are we as urban scholars to squeeze meaning out of these practices?

Reducing spiritual practices to fears or explanatory rationales dismisses their depth and embeddedness in Lamu society, and the ways in which people relate to other urban sites in the Indian Ocean through spirituality.

I consider relationality the starting point of connections across space and situate Lamu at the nexus of studies on spirituality (Larsen 2009, 2014; Ballarin 2009; Giles 2018; Uimonen & Masimbi 2021) and urban maritime literature (Menon et al. 2022, Mahajan 2022, Lavery & Hofmeyr 2020 Pugh 2013, Glissant 1997) to show how spirituality in Lamu creates an archipelagic space of connections between distant urban locales, that are both geographical, bodily, and more-than-material.

The first part of my study delves into the link between spirituality, water, and people, and shows how my interlocutors embody the island’s history of connectedness through spiritual practices around water (Meier 2017; Kosgei 2021). Interactions with tides reveal a deep spiritual connection to the sea, where tidal movements are seen as sacred and imbued with cleansing powers.

“I can read dua in Lamu and cure you in Dubai,” Hashid told me one evening during my fieldwork in Lamu, after explaining the various methods he uses as a healer (mtabibu), to cure people of being overcome by spiritual forces (Field notes 25.04.2024).

We sit in the living room of his home in Lamu Old Town. The room offers a tranquil and undisturbed space for our conversation, with the exemption of his two-year-old daughter, who at times seems fairly displeased that I take up her father’s attention. Despite her young age, it occurs to me that she is somehow aware of her father’s expertise, and conscious that I, a complete stranger, have come to her home to learn.

The general term for a spiritual force in Lamu is jinn (jinns or majinni in plural). There exist good and bad jinns. The good jinns do not disturb humans, while it is believed that the bad jinns bring all sorts of misfortune to people. The process of being “taken over” or “put out of control” by a spiritual force is conceived as spirit possession or dispossession. This is where Hashid’s profound knowledge of spirituality is most evident, as he has the ability to free people from spirit possession. As a mtabibu, he carries a jinn, that together with his religious faith, serves as a guiding force in his treatments:

“I have religion in one hand, and the jinn in the other” he states, and hands me his medical license issued by the social services.

Due to Lamu’s maritime connections to other nations in the Indian Ocean, the advent of Islam has led to an enduring influence on the cultural history of the port city. This research presents a study of spirituality on Lamu Island through a relational lens. For this, I ask the following questions: How does spirituality circulate through spaces in Lamu and across geographies? And how are we as urban scholars to squeeze meaning out of these practices?

Reducing spiritual practices to fears or explanatory rationales dismisses their depth and embeddedness in Lamu society, and the ways in which people relate to other urban sites in the Indian Ocean through spirituality.

I consider relationality the starting point of connections across space and situate Lamu at the nexus of studies on spirituality (Larsen 2009, 2014; Ballarin 2009; Giles 2018; Uimonen & Masimbi 2021) and urban maritime literature (Menon et al. 2022, Mahajan 2022, Lavery & Hofmeyr 2020 Pugh 2013, Glissant 1997) to show how spirituality in Lamu creates an archipelagic space of connections between distant urban locales, that are both geographical, bodily, and more-than-material.

The first part of my study delves into the link between spirituality, water, and people, and shows how my interlocutors embody the island’s history of connectedness through spiritual practices around water (Meier 2017; Kosgei 2021). Interactions with tides reveal a deep spiritual connection to the sea, where tidal movements are seen as sacred and imbued with cleansing powers.

Through rituals, Hashid uses the ebbs and flows as a medium to engage with spirits, invoking prayers to channel divine forces of the sea for protection and healing. Hashid’s practices connect him to a broader cultural and historical tapestry, reflecting an embodied spiritual relationship that links Lamu to other Indian Ocean communities.

After converging around the watery quality of spirituality in Lamu, I extend the analysis to a focus on the fringe between water and land as being a specifically dense spiritual space (Mahajan 2022; Kucher 1995).

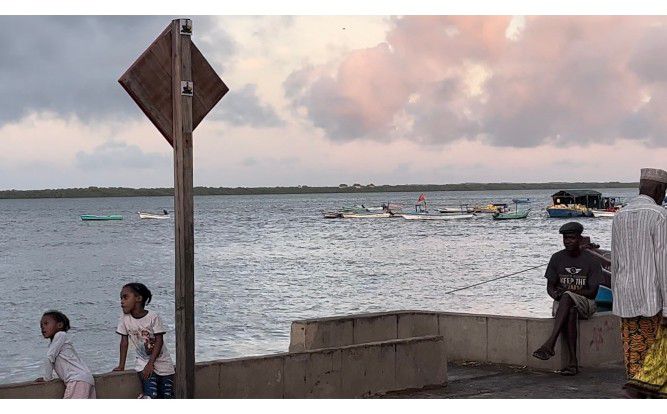

After converging around the watery quality of spirituality in Lamu, I extend the analysis to a focus on the fringe between water and land as being a specifically dense spiritual space (Mahajan 2022; Kucher 1995). My interlocutor Yunus’ memory of a spirit encounter near the main jetty of Lamu Old Town highlights the jetty’s unique role as a liminal space, where the boundary between water and land holds spiritual intensity and guides social behaviour. The materiality and the social relations played out around the jetty-space extends Mahajan’s concept of "archipelagic relationality".

The second part of my study explores the translocal nature of jinns in Lamu, and challenges the dichotomy between human and spiritual identities, suggesting a more integrated and archipelagic relationship between the worlds. Hasid’s recalling of his friend Issa’s possession by a Russian-speaking jinn exemplifies Ensing Ho's (2006) concept of "local cosmopolitanism.” I argue that this concept extends into the spiritual realm, where jinns also embody the junctures of local and global influences, which offers a critique of Larsen’s argument (2024) that the spiritual and human world are considered separate, though they are intertwined. I rather propose that spirituality in Lamu is regarded an inseparable part of the human world.

The last and third part proposes that modernity offers alternative ways of practicing spirituality in Lamu (Meier 2017). This argument is further deepened by a comment to Dilip Menon’s argument that migration across the oceanic distances creates a scale of its own (Menon et al. 2022: 8). Based on Hashid’s remarks “I can read dua in Lamu, and cure you in Dubai”, I suggest spirituality as a scale of it own.

The last and third part proposes that modernity offers alternative ways of practicing spirituality in Lamu (Meier 2017). This argument is further deepened by a comment to Dilip Menon’s argument that migration across the oceanic distances creates a scale of its own (Menon et al. 2022: 8). Based on Hashid’s remarks (“I can read dua in Lamu, and cure you in Dubai”), I suggest spirituality as a scale of it own.

Spirituality as a scale of its own creates alternative connections between spatial, temporal, emotional and socio- political elements and provides a pathway to think space less as a surface to move on or a scene for cultural practices or beliefs, and more of a medium to think about felt connections.

By exploring the role of jinns on Lamu Island, my study reveals the role of spirituality in Lamu as a means of cultural and historical relationality to the wider Indian Ocean world, where multiple spiritual practices intersect. Together they create an archipelagic space of connections between Lamu and distant urban locals that are both geographical, bodily, and more-than-material, demonstrating that spirituality circulates through numerous spaces in Lamu and across the Indian Ocean as process and result of many relations at a time.

Ways of Living #2403

Mangroves

We were on the boat, the sky was blue and the clouds were white.

I saw a lot of mangroves above the sea, like soldiers protecting the coast. Slowly darkness fell, and the forest became as silent as the dark night.

They are so mysterious, beautiful, and reliable, and it is said that elves live in them. I don’t want to talk about elves here. I want to consider their future.

Mangroves, which are a natural and cultural element of heritage in Lamu, have received a lot of attention due to the industrialization and urbanization of Lamu. Many institutions are trying to protect and restore them, such as the KFS (Kenya Forest Service), CFAs (Community Forest Associations), NGOs, and local communities.

I saw a lot of mangroves above the sea, like soldiers protecting the coast. Slowly darkness fell, and the forest became as silent as the dark night.

They are so mysterious, beautiful, and reliable, and it is said that elves live in them. I don’t want to talk about elves here. I want to consider their future.

Mangroves, which are a natural and cultural element of heritage in Lamu, have received a lot of attention due to the industrialization and urbanization of Lamu. Many institutions are trying to protect and restore them, such as the KFS (Kenya Forest Service), CFAs (Community Forest Associations), NGOs, and local communities.

What is the relationship between these institutions? What is the relationship between mangroves and local people? And are mangroves effectively protected?

This project focuses on the relationship between mangrove conservation groups, people, and mangroves themselves. The aim is to answer the following question: What kind of restoration method can better ensure that mangroves are effectively passed on to future generations as natural and cultural heritage?

If we still have a little compassion for the remaining species, if we really put ourselves in the middle of them, we will understand that animals and plants are as alive as humans.

Based on existing research and inspired by Calkins’ “empathy with plants”(2020), this project has preliminarily and poetically explored which of the several existing restoration methods is more conducive to restoring the mangroves themselves and restoring people’s relationship with them.

If we still have a little compassion for the remaining species, if we really put ourselves in the middle of them, we will understand that animals and plants are as alive as humans.

Based on existing research and inspired by Calkins’ “empathy with plants”(2020), this project has preliminarily and poetically explored which of the several existing restoration methods is more conducive to restoring the mangroves themselves and restoring people’s relationship with them.

Lifestyle

Work at sunrise and rest at sunset.

People pray, people sing.

The boat drifting with the sea,

The starry sky in sight.

Houses in the distance,

Waves close by,

Chatty backpackers.

All tell the stories...

People pray, people sing.

Children and donkeys are crying

from time by time.

However, you do not feel noisy at all,

You feel that, this is life itself.

The boat drifting with the sea,The starry sky in sight.

Houses in the distance,

Waves close by,

Chatty backpackers.

All tell the stories...

Forest and sea

If the forest is the habitat of the soul,

then the sea is the home of the wanderer.

Rare seabirds were low in the sky,

The moon showing half its face.

The clouds are like the white breasts of swans,

People running, laughing and crying.

Day after day, year after year,

Until the end of the world...

Sometimes, the darkness

extinguished the light of the clouds,

Just like the distant dreams.

Lonely old people,

Lost middle-aged people,

And the little ones,

Who do not know what they are doing...

Ways of Living #2404

Complexity and Contradiction in Ecology

“Will we allow anthrax or cholera microbes to attain self-realization in wiping out sheep herds or human kindergartens? Will we continue to deny salmonella or botulism micro-organisms their equal rights when we process the dead carcasses of animal and plants that we eat?”

(Chakrabarty 2021, 194)We meet in Hassan’s office on the first floor. Hassan is a community organizer, and he has arranged for us to speak with an Ustadh, a Muslim teacher and leader. My co-researcher has asked Hassan to set up the interview, and she has invited me to come along. Lamu is a majority Muslim community and before the Ustadh arrives, we chat with Hassan about the rules of Islam regarding the treatment of animals. The Ustadh, a man around 30 years old wearing a football jersey, feels most comfortable speaking in Kiswahili, so Hassan has volunteered to translate. Throughout, he also offers his own opinions at various points.

In the second half of the interview, after my co-researcher has asked her questions, we return to the topic of animals in Islam. The Ustadh explains that while the elders still follow the rules of the Qu’ran, younger people have lost their way and treat animals — from donkeys to ants — poorly. I ask if the rules extend to fish and Hassan takes a moment to explain something to me before translating:

“Okay, let me tell you something. In the sea, Islamically, everything that comes from the sea is edible.”

The Ustadh’s response is similar: “In the sea, there is no mistreatmeant. Because they're going there for fish, and fish is a meal. People will eat it, right?”

In Lamu, a historically seafaring town on the shores of the Indian Ocean, “70 percent of the local population depends on artisanal fishing.” (Lesutis 2022, p. 2438) A hierarchy of beings begins to emerge, with (differentiated) humans on top and a value-gradient of animals below. What seems at first glance to be an instance of the double fracture laid out by Malcom Ferdinand in his book Decolonial Ecology is quickly qualified by the Ustadh: “In a killing of this animal or insect, there is a way of killing. Like, for instance, we cannot kill a mosquito for consumption, right? But it's just for prevention. Because if you don't take care, we'll get malaria.” Malaria is a serious illness and can be fatal — fracture or not, preventive action is necessary for health and survival.

Still, I cannot shake the feeling that we have very different concepts of equality. Hassan explains that “we have rights, and animals have rights. So, it's equal. For Islam, it's very equal. You're not supposed to kill it without a reason. If you have a reason, you do it. […] That is Islam.” As a conscientious vegan, I want to think there is never a reason to kill a human or any other animal. One might reasonably ask what makes my drawing of the line between justified and condemnable in between plants and animals more valid than Hassan’s at the border in between animals and humans; I leave it to you, the reader, to consider this ethical quandary. No matter which version of equality you settle on, though, the Ustadh acknowledges that that is not how things are anyways:

Still, I cannot shake the feeling that we have very different concepts of equality. Hassan explains that “we have rights, and animals have rights. So, it's equal. For Islam, it's very equal. You're not supposed to kill it without a reason. If you have a reason, you do it. […] That is Islam.” As a conscientious vegan, I want to think there is never a reason to kill a human or any other animal. One might reasonably ask what makes my drawing of the line between justified and condemnable in between plants and animals more valid than Hassan’s at the border in between animals and humans; I leave it to you, the reader, to consider this ethical quandary. No matter which version of equality you settle on, though, the Ustadh acknowledges that that is not how things are anyways:

“We need to have equal rights for everything. But it is not practiced. It is only practiced to the direct benefit. […] Things are done for productivity. So, if something is not productive to me, I don't care about it. But there is a need for everything to be treated equally.”

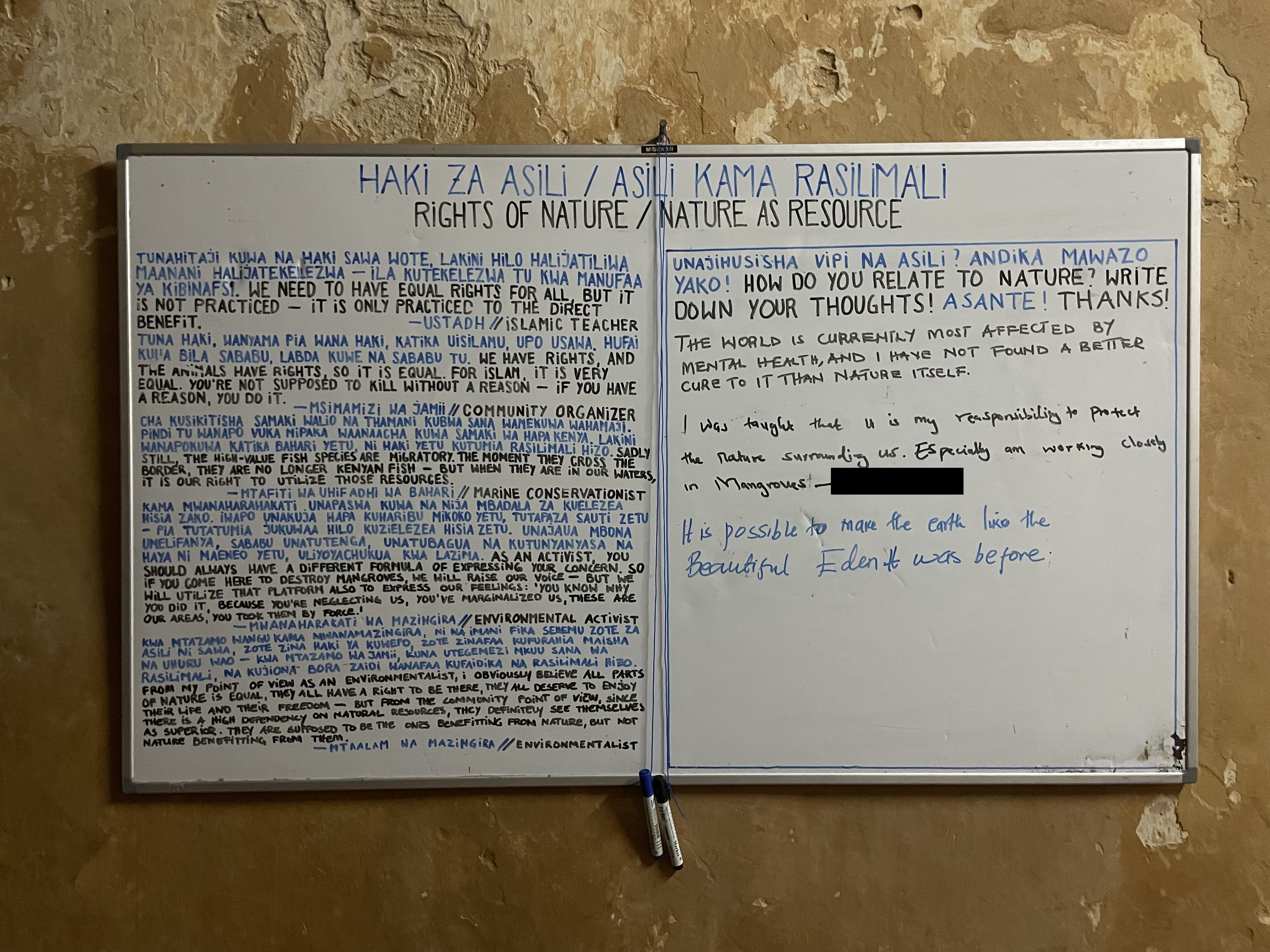

Haki Za Asili // Asili Kama Rasilmali

Rights Of Nature // Nature As Resource

Tunahitaji kuwa na haki sawa wote, lakini hilo halijatiliwa maanani, halijatekelezwa -ila kutekelezwa tu Kwa manufaa ya kibinafsi.

We need to have equal rights for all, but it’s not practiced — it’s only practiced to the direct benefit.

Tuna haki, wanyama pia Wana haki, Katika uisilamu, upo usawa. Hufai kuua bila sababu, labda kuwe na sababu tu.

We have rights, and the animals have rights, so it is equal. For Islam, it is very equal. You’re not supposed to kill without a reason — if you have a reason, you do it.

Cha kusikitisha samaki walio na thamani kubwa sana wamekuwa wahamaji. Pindi tu wanapo vuka mipaka waanaacha kuwa samaki wa hapa Kenya. Lakini wanapokuwa katika bahari yetu, ni haki yetu kutumia rasilimali hizo.

We need to have equal rights for all, but it’s not practiced — it’s only practiced to the direct benefit.

— Ustadh / Islamic Teacher

Tuna haki, wanyama pia Wana haki, Katika uisilamu, upo usawa. Hufai kuua bila sababu, labda kuwe na sababu tu.

We have rights, and the animals have rights, so it is equal. For Islam, it is very equal. You’re not supposed to kill without a reason — if you have a reason, you do it.

— Msimamizi wa Jamii / Community Organizer

Cha kusikitisha samaki walio na thamani kubwa sana wamekuwa wahamaji. Pindi tu wanapo vuka mipaka waanaacha kuwa samaki wa hapa Kenya. Lakini wanapokuwa katika bahari yetu, ni haki yetu kutumia rasilimali hizo.

Sadly still, the high-value fish species are migratory. The moment they cross the border, they are no longer Kenyan fish — but when they are in our waters, it is our right to utilize those resources.

— Mtafiti wa Uhifadhi wa Bahari / Marine Conservationist

Kama mwanaharahakati unapaswa kuwa na njia mbadala za kuelezea hisia zako. Iwapo unakuja hapa kuharibu Mikoko yetu, tutapaza sauti zetu — Pia tutatumia jukuwaa Hilo kuzielezea hisia zetu. Unajaua mbona umelifanya, sababu unatutenga, unatubagua na kutunyanyasa na haya ni maeneo yetu,uliyoyachukua kwa lazima.

As an activist, you should always have a different formula of expressing your concern. So if you come here to destroy mangroves, we will raise our voice — but we will utilize that platform also to express our feelings: ‘You know why you did it, because you’re neglecting us, you’ve marginalized us, these are our areas, you took them by force.’

— Mwanaharakati wa Mazingira / Environmental Activist

Kwa mtazamo wangu kama mwanamazingira, Ni na Imani fika sehemu zote za asili ni sawa,zote zina haki ya kuwepo, zote zinafaa kufurahia maisha na uhuru wao — Kwa mtazamo wa jamii, Kuna utegemezi mkuu sana wa rasilimali, na kujiona bora zaidi wanafaa kufaidika na rasilimali hizo .

From my point of view as an environmentalist, I obviously believe all parts of nature is equal, they all have a right to be there, they all deserve to enjoy their life and their freedom — but from the community point of view, since there is a high dependency on natural resources, they definitely see themselves as superior. They are supposed to be the ones benefitting from nature, but not nature benefitting from them.

As an activist, you should always have a different formula of expressing your concern. So if you come here to destroy mangroves, we will raise our voice — but we will utilize that platform also to express our feelings: ‘You know why you did it, because you’re neglecting us, you’ve marginalized us, these are our areas, you took them by force.’

— Mwanaharakati wa Mazingira / Environmental Activist

Kwa mtazamo wangu kama mwanamazingira, Ni na Imani fika sehemu zote za asili ni sawa,zote zina haki ya kuwepo, zote zinafaa kufurahia maisha na uhuru wao — Kwa mtazamo wa jamii, Kuna utegemezi mkuu sana wa rasilimali, na kujiona bora zaidi wanafaa kufaidika na rasilimali hizo .

From my point of view as an environmentalist, I obviously believe all parts of nature is equal, they all have a right to be there, they all deserve to enjoy their life and their freedom — but from the community point of view, since there is a high dependency on natural resources, they definitely see themselves as superior. They are supposed to be the ones benefitting from nature, but not nature benefitting from them.

— Mtaalam wa Mazingira / Environmentalist

Mvuvi chake ni unga– the fishermen goes with the flour

This Swahili proverb was quoted by a Lamu County executive committee member, who used it to explain the precarious situation of fishermen in Lamu today. According to him, “go with the flour” is translatable to the english proverb living from the hand to the mouth. Although fishing and fishing-related business is one of the main income sources of coastal communities in the Lamu archipelago, many fishers live day to day and with little means. In recent years, they have faced multiple challenges such as rising fuel prices and loss of access to good fishing grounds as a result of LAPSSET, a major regional infrastructure project. The health of fish populations and their ecosystems is under pressure from ocean warming, pollution, and illegal fishing practices, all of which damage the fish population and decrease overall biodiversity.

While this description depicts a challenging situation, it is only a momentary state of a dynamic field. Starting a few years ago, connected through the term Blue Economy, a plethora of programs and policies where initiated, which should help the socioeconomic development of coastal communities while introducing measures to protect life in the ocean. The Kenyan government and external actors such as the World Wildlife Foundation, the World Bank and the European Union are mobilizing the term Blue Economy in their programs with the promise to uplift fishers from poverty, develop the market capacity and meanwhile ensure a better security and environmental protection in the coastal waters.

Research goal

The goal of this research was to understand the interplay of different programs and policies active in Lamu and their related ambitions and challenges.

Therefore I approached the topic from two sides. On the one hand, I studied the context and ambitions of programs which use the term “Blue Economy” and the recent development of governing structures in the Kenyan maritime and costal domain. On the other hand, I conducted interviews with fishermen, NGO workers, and local government representatives in order to learn about the interests, lived experiences, and challenges faced in the implementation of different programs and policies.

Interventions

Current developments in the Blue Economy are heralded by stating their ambitions to help fisherfolk have more stable incomes, to protect the marine environment, and simultaneously increase production.

This should be facilitated by creating alternative income sources for some, while providing others with boats big enough to exploit the fish resources further out in the EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone). Meanwhile, the fisherfolk practicing near coast fishing should participate in the management of the co-managed areas, in which temporary closures allow the fish population to recover.

Co-managed areas are relatively nascent and although often mentioned as a key part of the solution, they are still far from a common sight. Offshore fishing is often spoken of, but so far the Lamu Archipelago lacks the cooling infrastructure to even support the current catch.

Though many plans exist and large sums of funding have been invested, most of the fishermen still go with the flour.

Though many plans exist and large sums of funding have been invested, most of the fishermen still go with the flour.

New Markets

What will come with quite high certainty is a new landing site with cold storage capacities, an adjacent marketplace and processing plant for fish and seafood in Mokowe. This will help to build the aspired deep sea capacity and, thanks to more direct access to the international market, likely increase potential profits. Whether boat owners will stay as intermediaries or whether government initiatives to give the fisherfolk access to sell directly in the market remains to be seen when it is built.

Conflicting with the hope to get the now too numerous fisherfolk to find other occupations, the potential higher incomes enabled through this new market access combined with the scarcity of other job opportunities could have an adverse effect.

Ultimately, while changing the sector might take some time, overfishing and ocean warming induced changes are accelerating. Coral bleaching related to the 2023-2024 El Niño has shown how sensitive the coral ecosystem reacts to temperature changes. On top of that, the environmental impact the further construction and operation of the LAPSSET Port will put additional stress on the ecosystems.

Outlook

Since leaving Lamu in May 2024, compensation for livelihood loss caused by the first part of the LAPSSET Port construction was finally paid, after many years of waiting.

This spurs hopes that fishermen will be able to invest in alternative income sources or their own equipment to reduce the dependencies on boat owners as middle men.

In June 2024, massive protests against the new financial bill, which would have further increased gas prices, have forced President William Ruto to renounce the bill and replace his entire board of ministers. I conducted my research in a moment when many things were changing, on different scales at different speeds. What comes of it remains to be observed in the future.