Urbanisation at the Margins

How are the peripheral settlements of Kashmiri and Kandahari evolving, and what does this tell us about the power to shape the urban?

Authors:

Eleonora Balestra

Hamdat Fathi Mahmud

Fatma Sayyid Athman

Joëlle Martz

By adopting a historical lens, our research traced the stories and memories of those who have built and inhabited Kashmiri and Kandahari over decades of its incremental yet continuous urbanisation.

These stories revealed the many ways in which residents navigate fragmented land tenure, engage in tacit negotiations with neighbours, and cope with the ambiguous status of their neighbourhoods within the frameworks of urban governance that are currently gaining relevance and capacity in Lamu.

![]()

Eleonora Balestra

Hamdat Fathi Mahmud

Fatma Sayyid Athman

Joëlle Martz

By adopting a historical lens, our research traced the stories and memories of those who have built and inhabited Kashmiri and Kandahari over decades of its incremental yet continuous urbanisation.

These stories revealed the many ways in which residents navigate fragmented land tenure, engage in tacit negotiations with neighbours, and cope with the ambiguous status of their neighbourhoods within the frameworks of urban governance that are currently gaining relevance and capacity in Lamu.

“Some would term what is happening in these settlements as classical urban sprawl. There isn’t much order; the only authority present at that time were the original land owners, who allowed the people to settle there. The way they build is very different to the old town [...] these are the houses of their own dreams.”

- Resident of Lamu Town

affiliated with the

National Museum of Kenya

Constant tacit or explicit negotiations characterise informal urbanisation in Kashmiri and Kandahari, which stands in sharp contrast to the municipality’s practice of marking new structures that don’t fit regulatory norms with a bright red ‘X’. These visual markers point to tensions that result from growing enforcement capacities of rigid laws, recently published land-use plans, and broader development projects that mismatch more incremental, negotiated ways of urbanising.affiliated with the

National Museum of Kenya

Urbanisation in these settlements is shaped by both necessity and hope for future recognition.

Projects

Urbanisation at the Margins #2501

Mutual Accommodation and its Temporalities: Lessons from Peripheral Urbanisation in Lamu

On my daily walks through the narrow streets of Kashmiri and Kandahari, I developed a little guessing game. Whenever I came across new red markings on bare, unplastered walls, I would try to guess what might have led the municipal surveyors to judge a particular building as failing regulations. Most of the time, I had barely a clue. But what grew from these regular observations of red X’s along my routes was a much more pressing question:

How do the residents here, the people I had come to think of as neighbours, respond to the growing presence of local urban authorities? And how does this shape the production of urban space, which until now had been almost entirely in the hands of those who call this place home?

![]()

To this day, Kashmiri and Kandahari are shaped by self-building practices, but formal rules are starting to have a greater influence as the local government becomes larger and more effective in enforcing them. This research looks at how urban spaces are being shaped through the ongoing interaction between everyday building practices and official regulations.

How do the residents here, the people I had come to think of as neighbours, respond to the growing presence of local urban authorities? And how does this shape the production of urban space, which until now had been almost entirely in the hands of those who call this place home?

To this day, Kashmiri and Kandahari are shaped by self-building practices, but formal rules are starting to have a greater influence as the local government becomes larger and more effective in enforcing them. This research looks at how urban spaces are being shaped through the ongoing interaction between everyday building practices and official regulations.

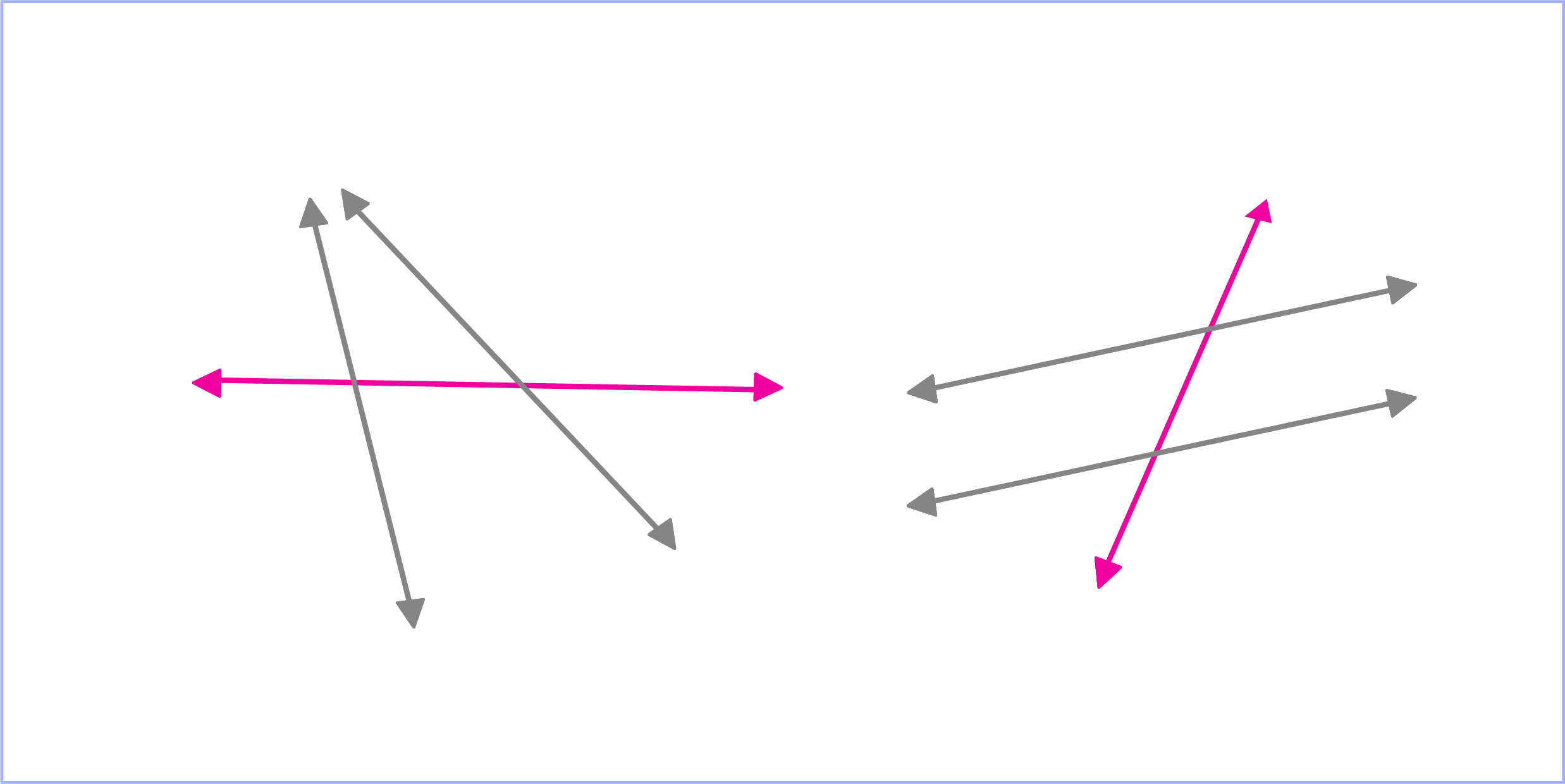

In Kashmiri and Kandahari, it is common for people to build their own houses, either by constructing them themselves or hiring professionals. Hardly a day passes without the sounds of construction nearby or the sight of donkeys carrying sand or building blocks through the streets. Prominent urban anthropologist Teresa P.R. Caldeira has described what is happening here as “peripheral urbanisation.” She theorises it as more than just development at the physical edges of a city; rather, it is a mode of producing urban space that is driven by the agency of residents themselves. Tied to financial means and personal opportunities, this process is typically incremental and interacts with formal markets and governance systems in ways that cross and connect these seemingly separate spheres. Such relationships are often described as transversal.

“transversal” is something that moves sideways and thus crosses boundaries — between formal and informal, powerful and less powerful, official and unofficial worlds.

Re-Engaging Informality

To explore and describe the interactions between residents and local government, I chose to use the terms formal and informal — a distinction that many influential scholars have criticised for decades. Building on these critiques, this study takes a closer look at the complexities of informal spaces.

The disenfranchised express a deep desire to live an informal life, to run their own affairs without involving the authorities or other modern formal institutions” (Bayat 1997, 53)

The disenfranchised express a deep desire to live an informal life, to run their own affairs without involving the authorities or other modern formal institutions” (Bayat 1997, 53)

It is important not to think of informality only as the opposite of official, state-defined rules, as it is more than the absence of such. It is an alternative form of social organisation. Flexibility, adaptability, and openness to negotiation may support people who are commonly excluded from formal systems. Though often connected to poverty, informality isn’t limited to people with low incomes. Middle-class people, too, increasingly live, work, and invest in informal spaces.

Everyone can engage with informality; some have the privilege to do so quietly, while others carry that label openly on their shoulders.

Everyone can engage with informality; some have the privilege to do so quietly, while others carry that label openly on their shoulders.

Tracing the In-Betweens

The foundations of urban life in Kashmiri and Kandahari are built on informally subdivided land, where former shambas (Kiswahili for agricultural land) were split and sold by their owners. As urbanisation gradually built over the small path that once separated these plots, the municipal garbage truck, which used to pass through to reach the town’s main dumping site behind Kandahari, was forced to find new routes. Over time, a new path, commonly referred to as TakaTaka road (TakaTaka is a Kiswahili term for garbage), emerged there, where unequal opportunities to build left plots empty.

Today, the municipality relies on this informally developed infrastructure, but it is mainly the residents who actively defend it. When someone attempts to lay a foundation for a new house on this road, others tend to whistleblow immediately. As a result, state enforcement is typically quick to show up at the construction site to intervene and halt construction attempts within hours.

The case of the TakaTaka road shows how the formal system sometimes works with informal structures to help achieve its own goals, while people involved in informal activities may use formal rules to advance their interests.

The way the TakaTaka road emerged is a good example of ‘mutual accommodation’ — a term used by urban scholar Carole Rakodi to describe how formal and informal actors work together to get access to land in African cities. My research shows that this idea also helps explain what’s happening in Kashmiri and Kandahari today.

As formal and informal actors adjust to one another, they sometimes, whether intentionally or not, help to legitimise each other’s actions. This is how mutual accommodation takes shape.

The case of the TakaTaka road shows how the formal system sometimes works with informal structures to help achieve its own goals, while people involved in informal activities may use formal rules to advance their interests.

The way the TakaTaka road emerged is a good example of ‘mutual accommodation’ — a term used by urban scholar Carole Rakodi to describe how formal and informal actors work together to get access to land in African cities. My research shows that this idea also helps explain what’s happening in Kashmiri and Kandahari today.

As formal and informal actors adjust to one another, they sometimes, whether intentionally or not, help to legitimise each other’s actions. This is how mutual accommodation takes shape.

Listening to Urban Rhythms

The people of Kashmiri and Kandahari have been shaping their neighbourhoods through mutual accommodation long before state institutions became involved in these areas. This study found that their incremental ways of building — a new wall here, a small extension there — make it easier for neighbours to adjust to one another over time. These slow, flexible timelines, shaped by gradual, adaptive, and sometimes opportunistic actions, allow people to create their own forms of acceptance and legitimacy, outside any formal rules or laws.

In contrast, formal planning tends to arrive with strict, project-based timelines and fixed ideas about what should happen and when. These big projects rarely leave room for the kinds of everyday negotiations that allow residents to quietly accommodate one another. Without this slow process of adjustment, formal interventions can easily feel disruptive, even threatening, and often struggle to gain acceptance within the community.

The frictions and accommodations evident today will shape the evolving relationship between state authority and resident agency in the future, as planning efforts continue to permeate the informal urban fabric of Kashmiri and Kandahari.

The frictions and accommodations evident today will shape the evolving relationship between state authority and resident agency in the future, as planning efforts continue to permeate the informal urban fabric of Kashmiri and Kandahari.

Women, Migration and Everyday in Wiyoni

How do (migrant) women in Wiyoni construct a sense of belonging and sustain their everyday lives? How are these actions further related to the social and physical dimensions of infrastructure?

Authors:

Svenja Jakob

Tefle Mohammed

Rebecca Rodrigues

Lilian Salama

Natalia Krikotina

Wiyoni is a new and rapidly growing settlement in Lamu, home to a diverse population of both long-time Lamu residents and newcomers. This theme addresses the broad meaning of infrastructure in the context of Wiyoni, with a particular focus on the combination of its physical and social dimension. One notable example is the planned road connecting Wiyoni to other parts of the island and the support networks that emerge within the community in response to its construction.

![]()

S. in front of her shop

Many women in Wiyoni have migrated from other parts of Lamu County or the Kenyan coast in search of better economic opportunities for their families. However, migration often presents challenges, such as finding affordable housing, building new social connections, and overcoming the stigma of being an outsider. Despite these challenges, women remain prominent figures in Wiyoni's daily economy. They run small businesses selling juices, mahamri, ice cream, ice, and baobab snacks, and they also run cafes, beauty salons, and shops, catering to both their own needs and those of the community.

![]()

M. and family preparing baobab snacks

Svenja Jakob

Tefle Mohammed

Rebecca Rodrigues

Lilian Salama

Natalia Krikotina

Wiyoni is a new and rapidly growing settlement in Lamu, home to a diverse population of both long-time Lamu residents and newcomers. This theme addresses the broad meaning of infrastructure in the context of Wiyoni, with a particular focus on the combination of its physical and social dimension. One notable example is the planned road connecting Wiyoni to other parts of the island and the support networks that emerge within the community in response to its construction.

S. in front of her shop

Many women in Wiyoni have migrated from other parts of Lamu County or the Kenyan coast in search of better economic opportunities for their families. However, migration often presents challenges, such as finding affordable housing, building new social connections, and overcoming the stigma of being an outsider. Despite these challenges, women remain prominent figures in Wiyoni's daily economy. They run small businesses selling juices, mahamri, ice cream, ice, and baobab snacks, and they also run cafes, beauty salons, and shops, catering to both their own needs and those of the community.

M. and family preparing baobab snacks

To understand the forces that shape life and business in Wiyoni, the research team interviewed local residents, including shop owners, community leaders, newcomers, as well as officials from the municipality. The findings highlight the challenges of accessing education, finance, infrastructure, social connections, and security, and reveal how women navigate these challenges to sustain their lives and livelihoods.

H. making mahamri at home during an informal interview

Projects

Women, Migration and Everyday in Wiyoni #2502

The Challenges of Women-Owned Businesses in Wiyoni

Before going to Lamu, my own thoughts about how Islamic society is organised and the potential challenges for local women to develop businesses freely would flash through my mind like subliminal frames. Having had experience interacting with Muslim communities before, I understood the differences in our views and wasn’t sure I would be able to feel free there, both as a woman and as a white tourist/researcher. From the first days, immersing myself in the details of local life thanks to living with host families, the traditions and rules of relationships between men and women became clearer and clearer.

![]()

Understanding the local relationship system, I relaxed a little and sank into just “being,” trying to stay more in the here and now rather than in my thoughts.

Having spent the first week studying Lamu for myself, we then moved on to interviews with local residents. We asked about infrastructural problems but we were met with indifference to this topic from local people. We returned to exploring other dynamics affecting Lamu Island and the Wiyoni area in particular. We walked along sandy roads washed out by the rain, talking to local women about life in Wiyoni. Most of them had moved here from other places; some were Muslim, others Christian. Trying to build their new lives here, these women face the fact that their families lack basic means to survive. They try to earn money to feed their children and give them an education that they themselves never had. After talking to a dozen women and looking around, we saw what we hadn’t noticed before – women sitting in front of their homes selling food, working, or running their small shops. But why had we not seen what had been shining right into our eyes this whole time, like a sunbeam reflected off a piece of glass?

![]()

Understanding the local relationship system, I relaxed a little and sank into just “being,” trying to stay more in the here and now rather than in my thoughts.

Having spent the first week studying Lamu for myself, we then moved on to interviews with local residents. We asked about infrastructural problems but we were met with indifference to this topic from local people. We returned to exploring other dynamics affecting Lamu Island and the Wiyoni area in particular. We walked along sandy roads washed out by the rain, talking to local women about life in Wiyoni. Most of them had moved here from other places; some were Muslim, others Christian. Trying to build their new lives here, these women face the fact that their families lack basic means to survive. They try to earn money to feed their children and give them an education that they themselves never had. After talking to a dozen women and looking around, we saw what we hadn’t noticed before – women sitting in front of their homes selling food, working, or running their small shops. But why had we not seen what had been shining right into our eyes this whole time, like a sunbeam reflected off a piece of glass?

In Islamic society, a woman’s traditional role has been to care for the home and raise the children. Women still spend most of their time at home and when they run a business, it is often located at home or nearby. Women are “hidden” from strangers’ eyes, yet are an important part of Wiyoni’s social infrastructure.

The Covid-19 pandemic, which led to many divorces and a change in views on traditional family structure and household duties, challenged women to become more independent.

Analysing the knowledge we gained after several weeks of research, it became clear that women’s difficulties in Wiyoni are linked not only to Islam’s definitions of a woman’s place as interpreted in Lamu, but also to broader social changes. A lack of formal education, distrust in the state system, and, as a result, missed opportunities to seek support from organisations helping women’s businesses work together to create unique barriers for women-owned businesses.

While researching and trying to understand Wiyoni’s uniqueness in terms of women-owned businesses, I began wondering: is this case really unique in a global context? Studying works on Black feminism and feminism in general makes it clear that discrimination against women because of their gender, skin color, race, and social class is a pattern repeated on many pages of history. The struggles of building a business as not only a woman but also a newcomer to a community are deeply permeated with centuries of fighting for rights, facing discrimination, and striving for a brighter future. Yet, facing these challenges again and again, women coming with their families to live in Wiyoni continue their path, no matter what.

Women, Migration and Everyday in Wiyoni #2503

Kupatikana si Kukubalika:

Kupatikana si Kukubalika:

Belonging, Informality, and Moral Navigation Among Migrant Women in Wiyoni, Lamu

During a walk to Wiyoni, I noticed that one of the local people I had interacted with before was wearing her veil differently; in addition to her usual hijab, she was also wearing a niqab. Curious, I asked why. The answer came with gentleness, care, and a certain discomfort: she didn’t want to be recognized or associated with Wiyoni.

At first, I didn’t fully understand why. But as we talked more about it, I began to grasp (even if not explicitly) an unease in her words: a discomfort with how people from Wiyoni were perceived.

At first, I didn’t fully understand why. But as we talked more about it, I began to grasp (even if not explicitly) an unease in her words: a discomfort with how people from Wiyoni were perceived.

She described them as “modern,” influenced by outside customs, with different behaviors; almost as a threat, a stain on the expected moral conduct, or something that endangered tradition.

Research team during fieldwork in Wiyoni

Being associated with that neighborhood, or with the people who lived or circulated there, was a risk to her reputation within her own community. And in Lamu, community is one of the most valuable things a person can have. Beyond one’s immediate family, the community includes religious leaders, childhood friends, and neighbors — people you're taught from a young age to respect and keep close. It represents an extended network of financial, emotional, social, familial, and religious support; fundamental for belonging and success on the island: whether to get a job, to receive help in times of need, to secure housing, or to form a family.

In some way, this discomfort with the “new” or the “different” also echoed within the internal dynamics of this year’s research group, composed of researchers from UniBasel and LYA. During the last week, some local researchers shared their impressions, and it became clear that maintaining a relationship with us, foreign researchers, felt like walking a fine line. They enjoyed the company and accessed spaces they normally wouldn’t frequent, such as cafés, restaurants, interviewees’ homes, hotels, and more. Yet, at the same time, they felt a certain tension about what their families and the community might think. As different and external, we could represent a risk of moral influence. A possible departure from local norms and traditions.

In some way, this discomfort with the “new” or the “different” also echoed within the internal dynamics of this year’s research group, composed of researchers from UniBasel and LYA. During the last week, some local researchers shared their impressions, and it became clear that maintaining a relationship with us, foreign researchers, felt like walking a fine line. They enjoyed the company and accessed spaces they normally wouldn’t frequent, such as cafés, restaurants, interviewees’ homes, hotels, and more. Yet, at the same time, they felt a certain tension about what their families and the community might think. As different and external, we could represent a risk of moral influence. A possible departure from local norms and traditions.

It was in this friction, between visibility, belonging, and exclusion, that I began to perceive a deeper tension in Lamu, within the community and, beyond it, among its residents. Belonging in the local community was not a given, not even for those born there or connected through friendship or faith. There were subtle limits and unofficial but widely understood rules that determined who could occupy certain spaces, under what conditions, and when it was acceptable to slightly cross the line.

Members of the research team interviewing a local business owner in Wiyoni

That was the starting point of my seminar paper. Not a grand revelation, but a persistent discomfort perceived and observed. Something that repeated itself and resurfaced. I began to realize that everyday decisions, which I call performances, inspired by Sarah Hillewaert, such as what to wear or which route to take to a neighborhood, were not made solely on an individual basis, but also as deliberate actions in relation to others’ gazes, public opinion, and unspoken rules.

Reflecting on the daily experiences of the women in our research group, most of whom are originally from the island, and the impact of these dynamics on their lives, I shifted my focus to understand how such issues affect migrant women. In this context, Wiyoni proved to be a key place for this observation, as it is where most people from other parts of the country are concentrated on Lamu Island.

Reflecting on the daily experiences of the women in our research group, most of whom are originally from the island, and the impact of these dynamics on their lives, I shifted my focus to understand how such issues affect migrant women. In this context, Wiyoni proved to be a key place for this observation, as it is where most people from other parts of the country are concentrated on Lamu Island.

As a migrant, I recognize that moving involves profound changes in daily life and in how one envisions the future. However, my own migratory experience may differ significantly from that of the women in Wiyoni, whose motivations, circumstances, and contexts are distinct from mine. Therefore, when addressing social codes and forms of belonging in Lamu, especially in Wiyoni, it is essential to emphasize that these are specific contexts with their own dynamics that cannot be generalized to all migratory experiences. This diversity shows that the concept of “migrant” encompasses multiple realities, making it necessary to understand the specificities of each group in order to grasp the complexity of their trajectories. That said, it is possible to affirm that social codes vary everywhere, but I developed a particular curiosity about how these codes manifest in Lamu and, above all, in Wiyoni, where the senses of belonging were unfamiliar to me and had different complexities and carried different meanings.

For example, as a Brazilian living in Switzerland, I have had to adapt to certain local norms. However, most of the time, I do not feel obliged to behave “like a Swiss woman” and I believe I do not perform as such. The consequences of this, and the impact it has on my life, perhaps affect me less or matter less to me. But in Wiyoni, migrant women navigate codes that, if not followed, can compromise their support networks as well as their emotional, social, and even material security.

Of course, in any context, there are always individuals who, despite being aware of local social expectations, consciously choose not to follow them, and this is also a legitimate way of being. This is the case, for example, of the women who run the Wiyoni pub, who intentionally position themselves outside these rules, embracing the risks and possibilities that this stance entails.

For example, as a Brazilian living in Switzerland, I have had to adapt to certain local norms. However, most of the time, I do not feel obliged to behave “like a Swiss woman” and I believe I do not perform as such. The consequences of this, and the impact it has on my life, perhaps affect me less or matter less to me. But in Wiyoni, migrant women navigate codes that, if not followed, can compromise their support networks as well as their emotional, social, and even material security.

Of course, in any context, there are always individuals who, despite being aware of local social expectations, consciously choose not to follow them, and this is also a legitimate way of being. This is the case, for example, of the women who run the Wiyoni pub, who intentionally position themselves outside these rules, embracing the risks and possibilities that this stance entails.

This theme of non-belonging and adaptation to local rules came up repeatedly in our interviews with migrant women living in Wiyoni. They occupy the most sensitive and vulnerable edge of this social “chain.”

Local pub in Wiyoni

The question that has guided me since then is: how do these women (migrant, observed, scrutinized) construct a sense of belonging in a place that so often denies them legitimacy? How do they show the community whether they are (or are not) conforming to social norms?

Throughout the research, I realized that belonging in Wiyoni is constantly negotiated: never full, never guaranteed. For migrant women, this process is even more complex: beyond adapting to the material demands of life in a new place, they must also learn to navigate social codes that are often unknown or challenging.

Throughout the research, I realized that belonging in Wiyoni is constantly negotiated: never full, never guaranteed. For migrant women, this process is even more complex: beyond adapting to the material demands of life in a new place, they must also learn to navigate social codes that are often unknown or challenging.

Instead of seeking adherence to local norms (which are often exclusionary) many of them build alternative forms of belonging through horizontal alliances, informal exchanges, mutual support, and selective visibility. These practices compose a kind of social infrastructure that doesn’t appear on official maps but sustains life in Wiyoni. It is made of relationships, care, silent agreements; an everyday engineering that challenges the formal frameworks of institutional urbanism and reveals the strength of women as infrastructural agents.

At the intersection of vulnerability and agency, these women create small shifts at the boundaries of moral acceptability. Some perform respectability as expected; others publicly push against those limits and invent new ways of being. These performances (at times strategic, at others spontaneous) are not merely individual, but collective and situated. They draw a different moral cartography, in which belonging is not granted, but claimed.

By observing these dynamics, I came to understand that urban life in Wiyoni cannot be read solely through material infrastructures or official plans. It unfolds in the rhythms of everyday life, in the silences of interviews, in moments of self-censorship and rupture. It is in that space, between the visible and the invisible, that the city is made. And it is there that migrant women, with all their ambivalence, courage, and performance, sustain urban life.

Women, Migration

and Everyday in Wiyoni #2504

Infrastructural Assemblages in Wiyoni

The first connection one commonly makes with “infrastructure” is often physical, as the urbanist AbdouMaliq Simone describes (2004: 407). The physicality of infrastructure should also be understood in terms of that which is built by humans. This category then includes things such as roads, electricity networks, or ports. Field research in the neighbourhood of Wiyoni started from this point: inspired by the Kenya Informal Settlements Improvement Project (KISIP), I started to analyse the physical infrastructure of Wiyoni. KISIP plans to improve roads, street lights, and the sewage system in Wiyoni, as local interlocutors explained. However, being in the field and talking to the people who live in Wiyoni, we quickly realised that “infrastructure” consists of many more layers than these visible, physical objects. There are different social relations that are not visible at first sight, especially not as an outsider like the students from Unibas who don’t know about the cultural dynamics of the place.

From there on, I started looking out for “social” infrastructures during the field research. Social infrastructure includes relations people have with their neighbours, family and friends, and strangers, on an individual scale, as well as relations on the scale of the neighbourhood, the community elders (representatives of the neighbourhood), and towards the municipality, county government, or KISIP representatives.

Often, “physical” and “social” infrastructure are understood as separate from each other. This project critically reflects on this dichotomy and argues that they are indeed connected and influence each other. The many layers that “infrastructure” consists of form the place of Wiyoni and the daily lives of the residents. The project aims to shed light on this assemblage of different types of infrastructures, on understanding the making of Wiyoni, and to think of infrastructure as more than a human-built object.

Often, “physical” and “social” infrastructure are understood as separate from each other. This project critically reflects on this dichotomy and argues that they are indeed connected and influence each other. The many layers that “infrastructure” consists of form the place of Wiyoni and the daily lives of the residents. The project aims to shed light on this assemblage of different types of infrastructures, on understanding the making of Wiyoni, and to think of infrastructure as more than a human-built object.

Promises of Infrastructure

Street light built through KISIP

How physical and social infrastructure is connected and influenced is visible in the example of the KISIP project. One wish from the Wiyoni community, as well as the initial plan of KISIP, was to improve the neighborhood’s street lights.

They built one tall street light in the center, about 15 meters high, consisting of nine light bulbs. In that sense, the physical infrastructure was built and a promise kept. However, the light is not addressing the needs of the people, as it only lights up one small part of the neighbourhood. The physical infrastructure has an influence on how people move after dark, and further influences social ties, such as when and where to meet.

One request by the community that has not yet been addressed by officials is a market. People in Lamu usually buy fresh food (vegetables, fruits, meat, fish), usually at the market, which is located in the Old Town. The market is also a place of social interaction. Many women we talked to in Wiyoni expressed their desire for a market in Wiyoni in order to not have to go to the Old Town to buy the food. This is another example of a physical infrastructure that is tied to social interactions, as the market would not just provide people with food but also foster social relations as a place of gathering and simplify daily life by having easier access to products. Furthermore, it would allow more people in Wiyoni to have a business that could contribute to one’s income.

One request by the community that has not yet been addressed by officials is a market. People in Lamu usually buy fresh food (vegetables, fruits, meat, fish), usually at the market, which is located in the Old Town. The market is also a place of social interaction. Many women we talked to in Wiyoni expressed their desire for a market in Wiyoni in order to not have to go to the Old Town to buy the food. This is another example of a physical infrastructure that is tied to social interactions, as the market would not just provide people with food but also foster social relations as a place of gathering and simplify daily life by having easier access to products. Furthermore, it would allow more people in Wiyoni to have a business that could contribute to one’s income.

Social Ties

In our field research we mainly talked to women, as they were the focus of our research theme. Women doing business is another form of social infrastructure: First of all, women need customers to sell their products (such as baked snacks and sweets). If they know many people in the neighbourhood, it is easier to sell. Additionally, if they are well-connected to other women, they have easier access to the merry-go-round.

This is a collective fund in which women regularly pay a small amount of money. One after the other, each then receives a certain amount of money from the fund to invest in her business. This in turn contributes to the physical facilities of the neighbourhood, if a woman, for example, enlarges her store.

Time and Nature

A large part of Wiyoni consists of reclaimed land. In the 1990s, sand was extracted from the canal between Lamu Island and the mainland to enlarge the canal. Sand was put over the mangrove forest. Many buildings in Wiyoni are built on this land. The soil is eroding, which causes challenges for the building of houses and especially for sewage and water systems. These challenges further influence the daily lives of the residents, some of whom expressed their wish for improved access to water and sewage systems. Infrastructures are thus tied to the environment and, even though human-built, not separated from nature. Drawing on the work of geographer Andrew Barry (2016), the earth and soil is the infrastructure that physical, human-made infrastructure is constructed on.

Furthermore, the dimension of time shows, on the one hand, the transience of infrastructure, as nature (i.e. eroding soil) or material infrastructure can be demolished over time. On the other hand, it sheds light on how infrastructure is always in progress. Wiyoni is home to a variety of houses: at times painted buildings, at times only basic walls and a door.

Infrastructure is incomplete in the sense that it is an ongoing process: building new objects, negotiating projects and needs, getting to know new people and, perhaps, letting go of others.

Wiyoni from Above: Buildings located on reclaimed land in different stages of construction.

Uncovering Wiyoni’s Infrastructures

This project shows the layers of infrastructure that together form Wiyoni: human-built objects, relationships between people on different scales, the environment, and the dimension of time. It enables the reader to reflect on one’s personal relations to infrastructures, things that one might take for granted but emerge out of a process of social and political negotiation, power structures, and environmental circumstances.

The Space Between Work and Prayer

Where do working Muslim women pray outside the domestic space? And how do their prayer practices manifest spatially in Lamu?

Authors:

Nusrat Ahmed Ali

Khadija Bwanahamisi

Muanamkuu Salim Bake Ali

Samira Muster

Mara Pepine

Times are changing in Lamu. One of these changes is that women increasingly work outside of their homes. Islam teaches that it is most rewarding for a woman to pray at home and traditionally, Lamu women have largely stayed inside the home. But this does not apply to everyone. Nowadays, an increasing number of Muslim women play an active part in the economic life of the city. So, when the adhan is heard from all directions in Lamu town and their male colleagues go to the mosques to pray, where do these women go?

Our investigation also revealed how the different levels of assertiveness and claim-making on the part of the Muslim working women result in a variety of spaces being made available for prayer – from the storage cupboard to the female mosque. By exploring these spaces, we uncovered underlying connections between gender, culture, faith, labor conditions, and the spatial expansion of Lamu Town.

Taking ablution in the Women’s Mosque

As an all-women research team, we were able to explore how these Muslim women assert their presence in the city through newly emerging places of prayer and how the female embodied practice of Islam enables working Muslim women to shape and in turn be shaped by the spaces they inhabit.

Entrance to Raudha Women’s Mosque

Projects

The Space Between Work and Prayer #2505

Faith and Gender Consolidating Spaces in Lamu, Kenya

When investigating the topic of working Muslim women in Lamu, questions surrounding the lack of female mosques were answered time and time again with one word: “culture.” What is culture? And how is it different from religion? These are the questions on which I have built the theoretical framework that underpins my exploration of female religious practices outside of domestic space in Lamu Town.

![]()

“Most women in Lamu are not used to going to the mosques because of the culture”

– Abubakar & Hassan,

imams

imams

“We’re fighting with culture and religion.”

– Raya Famau, LWA

(in regards to women

empowerment)

(in regards to women

empowerment)

“Swahili people (women) do not use the mosque for prayer”

– Usthada Asya, teacher and radio moderator (regarding Swahili culture)

Due to an unstable and declining economy on the one hand, and a higher level of education on the other, more and more Muslim women are joining the workforce. In anticipation of the mega infrastructural project LAPSSET, the town is expanding, both in size and population. In this context, for many working Muslim women, praying at home is no longer a viable option.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework I am using lies at the intersection of three concepts: heshima, embodied piety, and respectability politics. In the Lamu context, heshima is of vital importance; literally “respectability” in Swahili, it represents the unspoken moral code that runs through the Swahili community. Theorized by the anthropologist Sarah Hillewaert as a “relational and performative network” (a system of behavior codes that apply to one’s role in the community and the mutual relationships between members), heshima relies heavily on Islamic values and morals, without, however, being one of the teachings of Islam. The way heshima functions in the Lamu context is very reminiscent of “respectability politics.” This concept, theorized by Evelyn B. Higginbotham in the U.S. context of African-American women and adapted to an African feminist perspective by Sylvia Tamale, refers to the strategies used by women to attain legitimacy in a patriarchal environment, by exercising social control over each other’s bodies and behavior.

In order to avoid the pitfalls of binary oppression-liberation narratives, I also introduce Saba Mahmoud’s concept of embodied piety. The anthropologist reframes agency not as resistance to norms, but as the ethical cultivation of the self through religious practices. Through this lens, the actions and choices undertaken by the women of Lamu in regards to their preferred spaces of prayer become proofs of agency and self-determination under the prevalent moral system, defined by the respectability politics of heshima.

![]()

Prayer and Spatial Negotiations:

Women’s Strategies in Daily Life

I apply this theoretical framework in order to reveal the socio-cultural reasons behind some of the more prevalent choices among Muslim working women in Lamu about where to pray. For instance, the choice to pray at home during lunch breaks has two underlying reasons: the Islamic prescription that teaches that women receive more spiritual rewards by praying at home and the more practical reason of having domestic responsibilities, like preparing lunch for the children.

This is where the spatial expansion of the town comes into play, as urban development becomes a hurdle in the most heshima-elevating prayer practices that working Muslim women can engage in. With longer distances and unreliable means of transportation, women can no longer easily go home on their lunch break to pray for dhuhr, the midday prayer. As such, they employ various strategies. Some visit the homes of relatives or friends that live closer to their place of employment, whereas others pray directly at their workplace, with a growing minority preferring to pray in the one accessible and adequate female mosque: Raudhwa Mosque.

The Role of Mosques

Generally, women pray in a mosque more often during Ramadan, as there are fewer domestic duties during the day, due to the fasting, which allows women to congregate en-masse in female mosques. Outside of Ramadan however, only one female mosque fulfills all the criteria to be properly used. In February 2025, Raudhwa Mosque opened its female section which, despite its small size, is bright, clean, and equipped with everything that women might need to fulfill their religious duties. It is also, as opposed to other mosques that have or have had a female section, conveniently located on the Seafront within walking distance from most workplaces that employ Muslim women. Raudhwa Mosque, however, is not perfect; most of the time it is locked and only a select few have a key and thus access to the building. Despite their popularization campaign, the mosque is still largely unknown by the women working within a radius larger than 100 meters.

The Culture-Religion Vicious Circle:

Why Women Don’t Pray in Mosques

The lack of female mosques in Lamu and the lack of visitors to those mosques reveals a vicious circle that proliferates at the intersection of religion and culture. Islam professes that it is more rewarding for a woman to pray at home and historically, most women did not leave the domestic space for prolonged periods of time. As such, it has become a part of the culture that women do not pray in mosques, which has been used as the reasoning behind the meager offering of female sections. The lack of appropriate space, in turn, makes women prefer the comfort and familiarity of their domestic space, further entrenching the idea that Muslim women in Lamu simply do not pray in mosques.

“Swahili people (women) do not use the mosque for prayer”

– Usthada Asya, teacher and radio moderator (regarding Swahili culture)

Improvised Sacredness:

Prayer in the Workplace

When praying outside of a domestic space, we can see women’s religious practices as a form of embodied piety, a way to express their agency in an environment that does not cater to them. Workplace prayer spaces are rarely institutionalized and thus often improvised. Offices, storage rooms, and the back rooms of shops take on a religious function through the act of prayer. However, these spaces, not being designed for such a function, are often lacking: too small, not clean enough, and occasionally without the proper ablution facilities. Regardless of their shortcomings, these improvised prayer spaces represent a way for women to appropriate and transform them in accordance with their religious needs, thus becoming an act of religious self-cultivation.

The Space Between Work and Prayer #2506

Gendered Contestations of Urban Space in Lamu, Kenya

Micropolitics of Prayer

Gendered Contestations of Urban Space in Lamu, Kenya

“How do Muslim working women’s prayer practices challenge the gendered cityscape of Lamu, fostering new female spaces of worship and increasing women’s presence in public areas?”

This research started from an interest in women’s spaces of prayer. While Muslim men usually pray five times a day at one of the 42 mosques in Lamu Town, Lamu’s Muslim women habitually pray in their homes. The recent increase in Muslim women engaging in non-domestic work is changing this. I was curious to first understand where the idea that women should pray at home comes from. From there, I was then trying to learn about these women's motivations for participation in the structural workforce and the changing needs that come with it. Lastly, I was looking at the way the practice of religion plays into this dynamic and the spatial manifestations of it.

In Swahili society, someone’s position in the social hierarchy used to be defined by their wealth, descent, and heshima (respectability). Having heshima is roughly defined by factors such as behaving respectfully and being a good Muslim. What that means in practice, though is constantly renegotiated amongst the members of Swahili society. An increased emphasis on heshima in the beginning of the last century led to the seclusion of women becoming a status symbol for the family. The effects of this practice had a substantial impact on the position of women in the public sphere, which is still palpable in Lamu today. Many places in town, especially the bigger streets, squares, the Seafront, and many workplaces, continue to be male-dominated, which leads women to either avoid them or navigate them with precaution. For a long time, women were also discouraged from pursuing higher education.

“Most women in Lamu are housewives. My mom didn't go to school. […]. In the past, Lamu girls didn't go to school, only the boys did. The common assumption was that the girl child is there for marriage. This was the culture.”

– Young Woman from Lamu

Today however, changes in Lamu’s economy and the rising level of education in women have led to their increased participation in the non-domestic workforce.

Working, for many of them, is much more than just a way to make money. It became clear to me that it is also a means to gain some independence and to open life paths beyond marriage and domestic duties. Through the insights of Belgian anthropologist Sarah Hillewaert’s study of Lamu’s youth, we also understand that these women see working, especially in NGOs and aid organisations, as contributing to development and therefore to the wellbeing of the town and its residents, contributing to their heshima.

At the same time, by joining the workforce, and with their increased presence in the streets and workplaces, Muslim women challenge the ever-present, unwritten rules of heshima. However, religion remains central in many of their lives, contradicting a western view of secularisation as a liberating element. For most of the women we spoke to, there was no doubt that they would continue their salat (the practice of their five daily prayers) when working. Scholars like John R. Bowen describe the Muslim daily prayers as one of the most visible aspects through which Muslims distinguish themselves from other religions, but also from one another and their varying degrees of religious observance. It therefore comes as no surprise that women in Lamu also employ their own religiosity to show that a practicing Muslim, a person with heshima, can also come in the form of a working woman.

![]()

A prayer room inside an office

The increased participation of Muslim women in Lamu's formal workforce is not merely an economic shift but a transformation of the city's social and spatial dynamics. As these women navigate the complexities of work and religious observance, they challenge traditional norms of heshima and redefine the gendered nature of public spaces. Their commitment to maintaining their daily prayers while engaging in non-domestic work emphasises the intricate relationship between gender, religion, and urban space. Through their everyday practices, these women are not only asserting their place in the city but also reshaping its urban fabric. The creation of new prayer spaces, from ad-hoc solutions to dedicated women's mosques, materializes their evolving needs and aspirations. My research highlights the importance of acknowledging and adapting to these transformations to cultivate more inclusive and equitable urban environments. The “micropolitics of prayer” utilized by these women stand as a compelling illustration of their agency and determination, embodying the continuous evolution of societal norms within Swahili society.

![]()

Outside Raudha Women’s Mosque

At the same time, by joining the workforce, and with their increased presence in the streets and workplaces, Muslim women challenge the ever-present, unwritten rules of heshima. However, religion remains central in many of their lives, contradicting a western view of secularisation as a liberating element. For most of the women we spoke to, there was no doubt that they would continue their salat (the practice of their five daily prayers) when working. Scholars like John R. Bowen describe the Muslim daily prayers as one of the most visible aspects through which Muslims distinguish themselves from other religions, but also from one another and their varying degrees of religious observance. It therefore comes as no surprise that women in Lamu also employ their own religiosity to show that a practicing Muslim, a person with heshima, can also come in the form of a working woman.

A prayer room inside an office

The increased participation of Muslim women in Lamu's formal workforce is not merely an economic shift but a transformation of the city's social and spatial dynamics. As these women navigate the complexities of work and religious observance, they challenge traditional norms of heshima and redefine the gendered nature of public spaces. Their commitment to maintaining their daily prayers while engaging in non-domestic work emphasises the intricate relationship between gender, religion, and urban space. Through their everyday practices, these women are not only asserting their place in the city but also reshaping its urban fabric. The creation of new prayer spaces, from ad-hoc solutions to dedicated women's mosques, materializes their evolving needs and aspirations. My research highlights the importance of acknowledging and adapting to these transformations to cultivate more inclusive and equitable urban environments. The “micropolitics of prayer” utilized by these women stand as a compelling illustration of their agency and determination, embodying the continuous evolution of societal norms within Swahili society.

“The opening of the women’s Mosque made me feel seen.”

– Working woman regularly praying at Raudha

Outside Raudha Women’s Mosque

Lamu’s Mkunguni Square

While some women go back to their homes at prayer time, through Lamu’s growing spatial expansion and the further distances, this is not always possible anymore, which leads to a new need for prayer places for women close to their workplaces.

I read the women’s everyday practices of working and especially praying in the city as acts of “micropolitics,” a term first coined by French philosopher Michel de Certeau in 1984, and taken up by Yasminah Beebeejaun, Professor for Urban Planning from the University College London. She appeals to planners to pay attention to women’s everyday actions and read them as acts of ‘micropolitics,’ to inform their planning and create more just cities for all genders. In the context of Lamu and other cities of the Global South, where the role of planning is distinctly different from a Western context, I argue that women’s ‘micropolitics of prayer’ negotiate symbolic but also physical space with the community and religious leaders. From small ad-hoc prayer spaces like a storage cupboard to more institutionalised spaces like the mosque dedicated to women, the material impact of this negotiation is manifold. The most prominent form of it is certainly the new creation of a mosque just for women, which enjoys great popularity amongst working Muslim women, but also serves travelling women as a temporary refuge in a city where there are not many other public spaces dedicated to women.

Inside Raudha Women’s Mosque