Themes

Ecologies of belonging

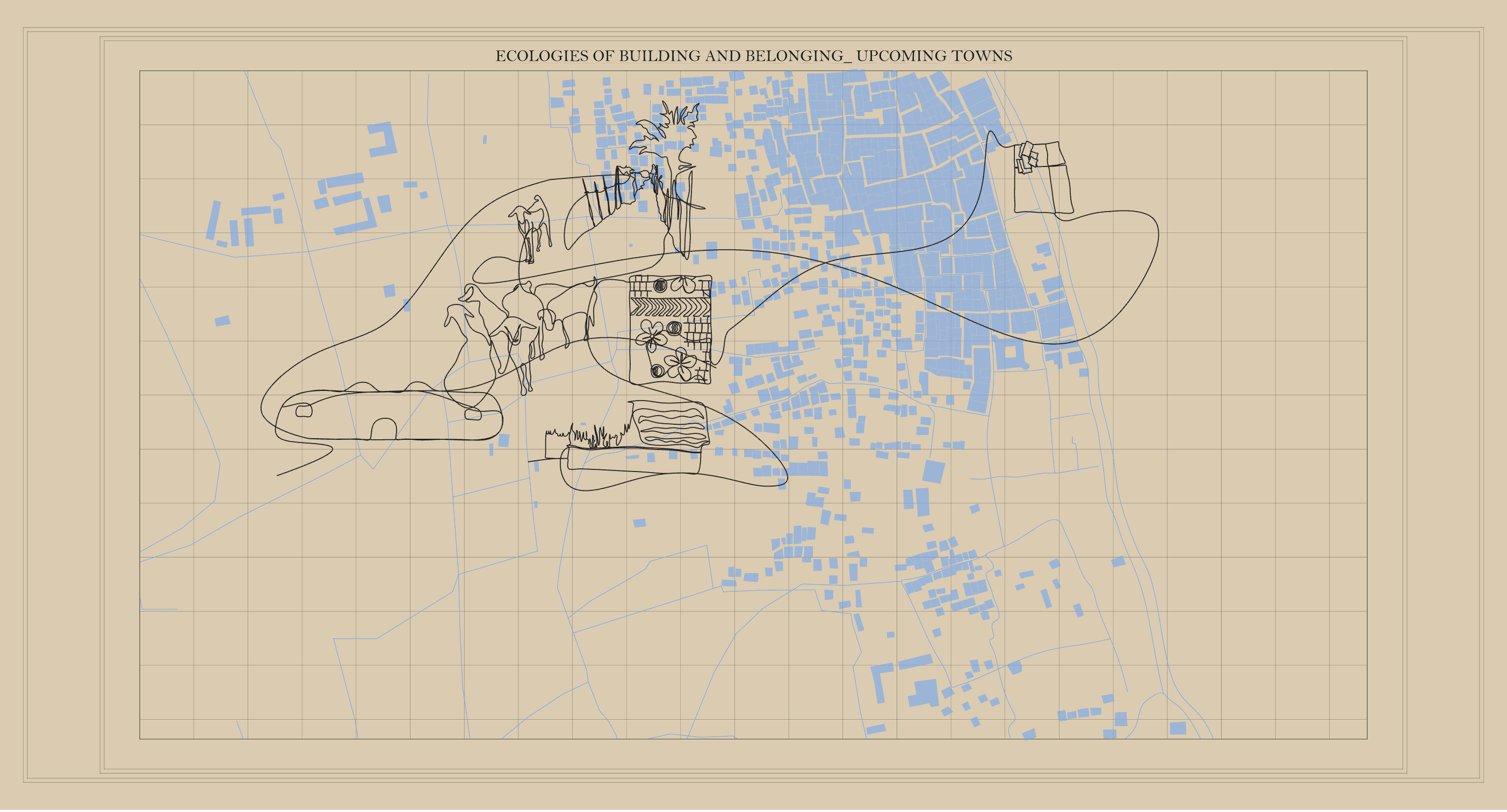

Due to the LAPSSET Corridor, the Lamu region is anticipating massive urban growth on the mainland. Yet much of this has yet to materialise. Meanwhile, Lamu island is experiencing its own construction boom. This theme explores how home-building is tied to people’s sense of belonging and to the broader ecology of the region.

Read more ︎︎︎

Maritime Mobilities

The new port promises future economic prosperity fueled by the smooth transportation of goods and people. But Lamu has been a regional and global node of trade for centuries, and mobility continues to be central to people’s lives. Our work focuses on the relationship between people’s ability to move and their ability to sustain themselves.

Read more ︎︎︎

Urban Stories of Displacement

LAPSSET’s promise of infrastructure-led development reactivates histories of displacement and forced resettlement in Lamu. This theme explores how these memories and hopes of return are shared and how they impact political claims to address historical and ongoing injustices.

Read more ︎︎︎

Heritage under Transformation

Lamu town has experienced significant urban growth since its inscription on the World Heritage List in 2001. Our work focuses on the ways in which Lamu negotiates the complex relationship between heritage preservation, changing domestic cultures, and new architectural and urban development.

Read more ︎︎︎

Security Urbanism

The Lamu region has suffered insecurity since the Shifta War. Current counter-terror securitisation is focused not only on infrastructure and construction sites but also on tourist and transport hubs. This theme explores the impact of securitisation on everyday life.

Read more ︎︎︎

Ecologies of Belonging

How does home-building shape people’s life stories and their sense of belonging in Lamu? What do common building materials such as coral stone and mangrove wood tell us about the future of Lamu?

Most new houses on Lamu island are built with local coral stones and mangrove wood. These ancient building materials are key to Lamu’s world-famous architectural heritage, yet home-builders often integrate them with modern techniques such as poured concrete. These building practices raise pressing questions of who belongs to Lamu.

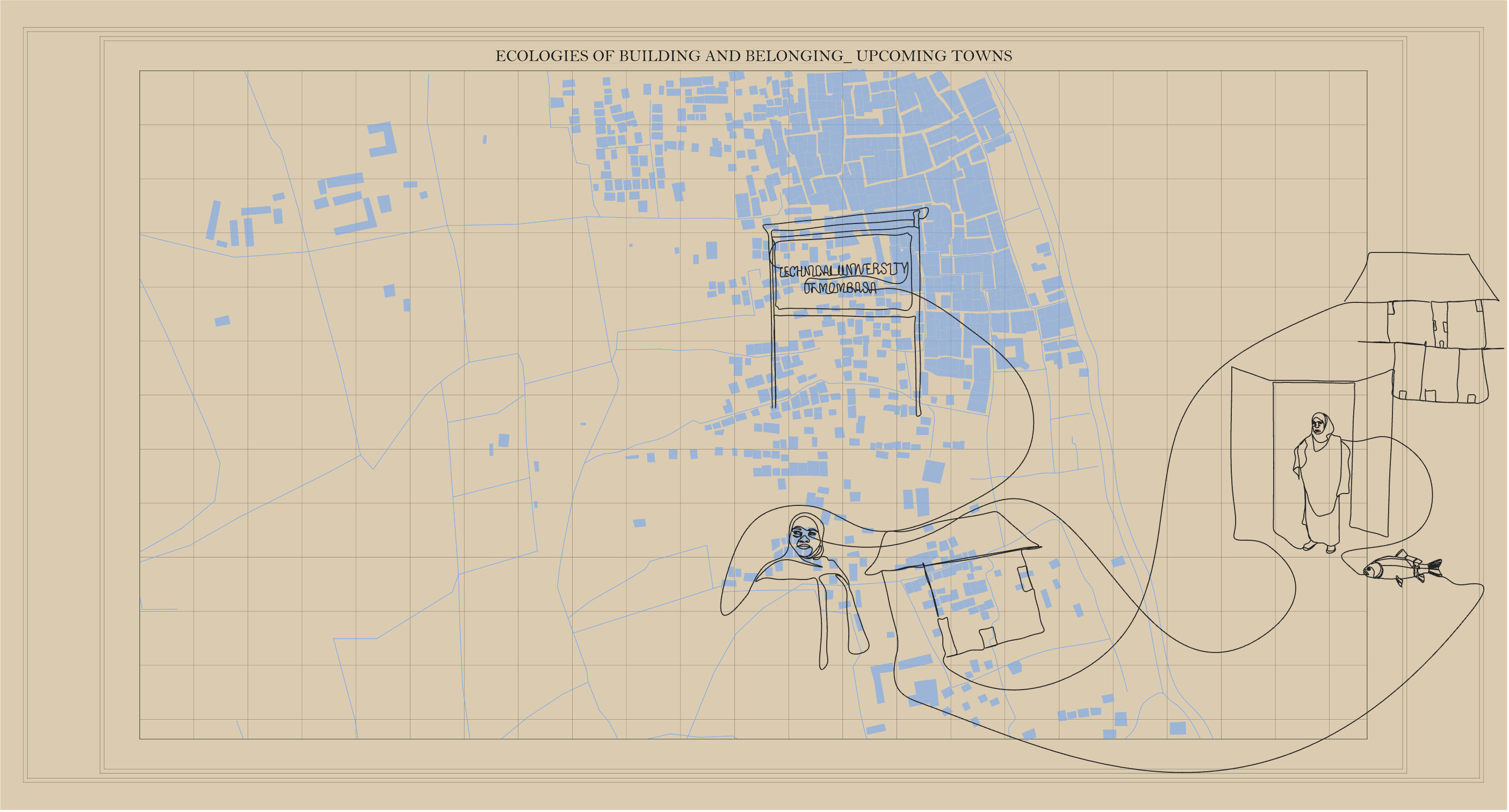

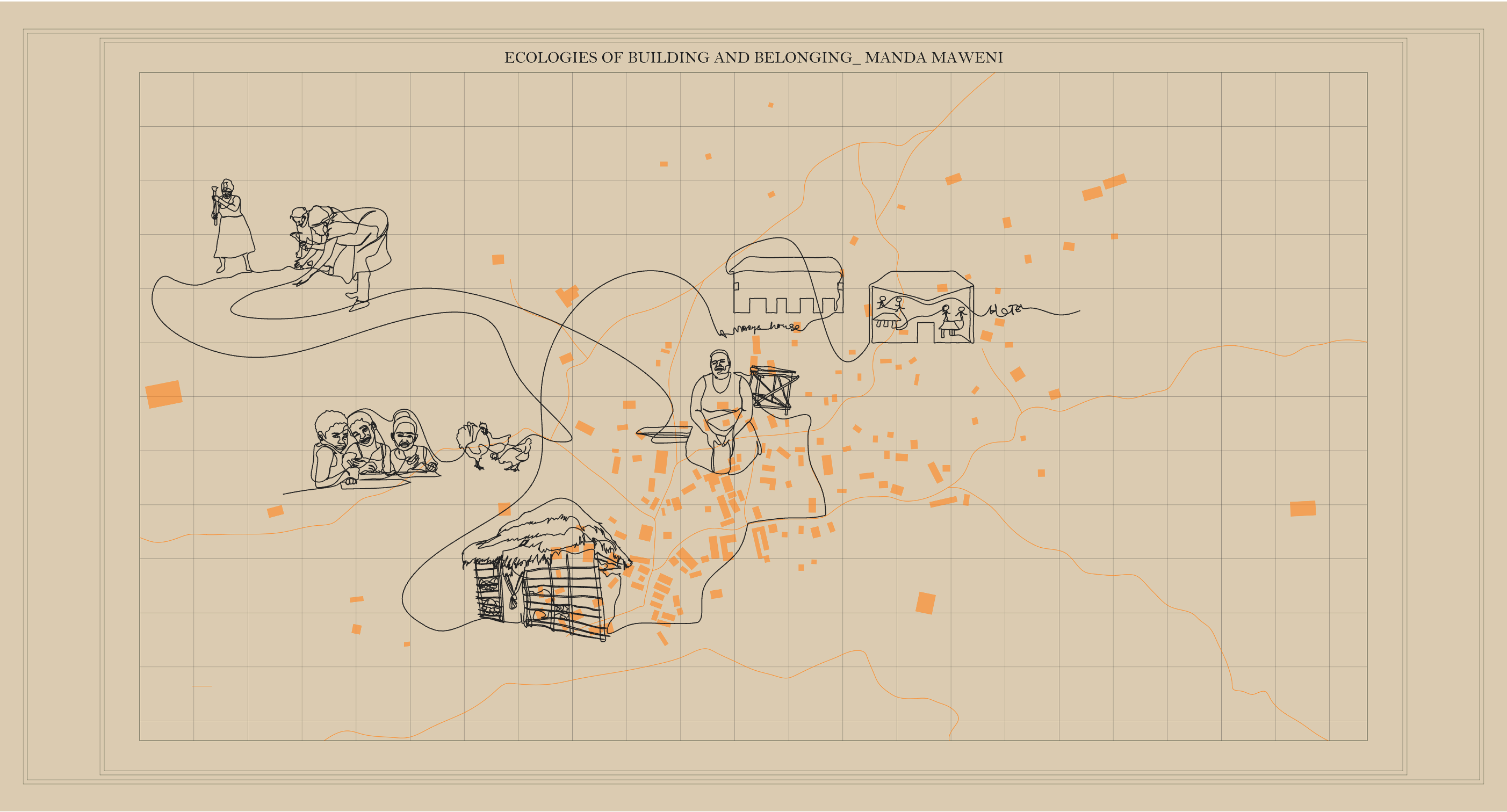

Lamu’s coral stones come from the quarry of Maweni on nearby Manda Island. Workers in this village carve the stones by hand from the coral stone bedrock of the island. They transport the stones by boat and donkey to Lamu, where they are used to build new houses on the outskirts of the historic town. Prospects of prosperity have long attracted people to work and live in Maweni, which has been a site of coral stone extraction since at least the 1980s. Many in this community of stone workers hail from western Kenya and are considered to be outsiders to the region.

Lamu’s coral stones come from the quarry of Maweni on nearby Manda Island. Workers in this village carve the stones by hand from the coral stone bedrock of the island. They transport the stones by boat and donkey to Lamu, where they are used to build new houses on the outskirts of the historic town. Prospects of prosperity have long attracted people to work and live in Maweni, which has been a site of coral stone extraction since at least the 1980s. Many in this community of stone workers hail from western Kenya and are considered to be outsiders to the region.

Our research focused on the relationship between Lamu and Maweni. What do they share? What separates them? And how do these communities depend on each other?

Building a house out of permanent materials is a common aspiration. Yet living in Lamu and Maweni comes with very different challenges. While most inhabitants of Lamu’s neighborhoods enjoy tenure, the inhabitants of Maweni face precarity and the risk of eviction. Few of their homes are built with the precious stones around which they have organized their livelihoods. Most homes in Maweni are made out of a combination of thatch, mud, and wood. Despite these inequalities, residents’ lives in both Lamu and Maweni are interlaced with complex stories of aspiration and belonging that are not contained by either of these locations.

Our urban research with community organizers, stone masons, house builders, home owners, and neighborhood residents combined hand drawing with photography, mapping, interviews and ethnographic walks. We used drawings and maps to convey the ecological relations of belonging that structure these stories. Someone’s sense of belonging cannot be easily pinned on a map or represented in a drawing, yet the dialogical practice of drawing together with community members allowed us to better understand what it means to belong.

Our urban research with community organizers, stone masons, house builders, home owners, and neighborhood residents combined hand drawing with photography, mapping, interviews and ethnographic walks. We used drawings and maps to convey the ecological relations of belonging that structure these stories. Someone’s sense of belonging cannot be easily pinned on a map or represented in a drawing, yet the dialogical practice of drawing together with community members allowed us to better understand what it means to belong.

Nasba’s story

Nasba comes from the coastal area of Kiwayuu, she is Swahili and Muslim. Nasba’s father is a fisherman and her mom owns a shop. She moved to Lamu Island for her studies because the university was close to home. She has been living in Lamu town ever since. Nasba still goes and visit her family in Kiwayuu - she buys groceries in Lamu and brings them to her mother’s shop. She initially lived with relatives and later moved from one rental apartment to another in the town.

Nasba comes from the coastal area of Kiwayuu, she is Swahili and Muslim. Nasba’s father is a fisherman and her mom owns a shop. She moved to Lamu Island for her studies because the university was close to home. She has been living in Lamu town ever since. Nasba still goes and visit her family in Kiwayuu - she buys groceries in Lamu and brings them to her mother’s shop. She initially lived with relatives and later moved from one rental apartment to another in the town.

This is why Nasba says she has so many neighbors. She greets all of them when she walks her streets. Today, she lives in Bombay, one of the new neighborhoods on the outskirts of the historic town. She rents an apartment there and has a close relationship with her neighbors, who she says are like family. In the future, Nasba wants to invest and build a big house back in Kiwayuu, and she also wishes to own a shop there. But she can also imagine living in Lamu, buying a plot of land and building a house of her own.

Mary’s story

Mary was born in central Kangundo in Machakos County. She is Christian and identifies as Kamba. She was brought up in Mpeketoni, where she attended school and learned Kiswahili and English. Her parents could not fully finance her education, so she started working on a farm when she was still young. Her husband was an alcoholic and could not provide for their four children. She divorced him and moved to Maweni for work all by herself. She first lived in a rented house and started working in the quarry to save money for her childrens’ education.

After ten years of hard work, she saved enough money to take over a restaurant lease and build a house of her own. She is currently renovating it with a tin roof and wishes to build a four-bedroom house. In the future, Mary also wants to build her own restaurant and manage employees in order to welcome more customers. Mary may decide to return to Mpeketoni in the future, but she does not think there will be work for her there.

Dida’s story

Dida was born in the nearby county of Tana River. She is Orma and Muslim. She came to Lamu town with her parents when she was six years old. Her family first lived in the neighborhood of Kandahari. Halima does not have any memories of her home village in Tana River. Her father lives in Witu, a town on the mainland, while her siblings are still living in Lamu Island. For work, Halima sells groundnuts, milk and tobacco in town. Sometimes, she sends her children to sell her products when they are not in school. She lives in her late husband's house together with them.

Dida’s house is a temporary structure made out of Makuti. She does not feel secure in her house because the land does not belong to her. It belongs to an old Swahili family of Lamu. She understands she is a squatter and can be told to go away anytime. She aspires to own a plot in Lamu town and build a permanent house of her own.

Projects

Ecologies of Belonging #2301

The Violence in Maweni’s Coral Stones

Maweni, 2023

Maeva Yersin

Download PDF

Maeva Yersin

Download PDF

Anticipating the economic prospects of the new port, the region has witnessed a surge in land speculation, sparking intensifying disputes about belonging in the region. These disputes encompass not only matters of land adjudication and ownership, patronage politics and corruption, but also about the stewardship and transformation of lived-in landscapes and ecologies.

Maweni is a small town nestled on Manda Island within the Lamu archipelago. Since the 1980s, people from various parts of Kenya have flocked to Maweni, attracted by the economic prospects offered by the local quarry. This quarry is pivotal in providing an ongoing supply of coral stones to Lamu town and the surrounding region. Coral stone, as the primary construction material of the town, carries profound cultural significance for Swahili coast residents, tightly interwoven with their sense of belonging, extending along the coastal expanse of Kenya.

Maweni is a small town nestled on Manda Island within the Lamu archipelago. Since the 1980s, people from various parts of Kenya have flocked to Maweni, attracted by the economic prospects offered by the local quarry. This quarry is pivotal in providing an ongoing supply of coral stones to Lamu town and the surrounding region. Coral stone, as the primary construction material of the town, carries profound cultural significance for Swahili coast residents, tightly interwoven with their sense of belonging, extending along the coastal expanse of Kenya.

In contrast to the predominantly Muslim population of the Swahili coast, Maweni's workers and residents, recently counted to be around 2,000 people, are mainly Christian. Many identify as Luo—an ethnic identification of communities initially settled around Lake Victoria in Western Kenya.

![]()

A shipment of coral bricks from Maweni, stacked at Lamu waterfront

A shipment of coral bricks from Maweni, stacked at Lamu waterfront

Postcolonial politics in stone

Coastal Kenya’s prevailing political landscape bears the marks of colonial history. European-imposed racial hierarchies intersect with Arab culture and Muslim notions of belonging within a Christian-dominated Kenya. The ambiguous relationship of coastal communities with “Kenya” can be traced back to the British colonial era when Swahili-speaking communities were racially classified as distinct from Africans. Compounding such clafficiations is the fact that since Kenyan independence, coastal communities have suffered state-led marginalization, manifesting in absent or deteriorating infrastructure, imposed security, and limited education and employment opportunities.

Perceptions of neglect by the postcolonial state have intensified the idea of a distinctive coastal identity, which serves both to gain political legitimacy and establish an alternative narrative of belonging independent of the Kenyan nation-state. How do these complex politics of belonging inhabit building materials such as coral stone?

Since the 12th century, coastal communities have utilised coral stones to construct houses, tombs, and mosques, thereby transforming coastal towns such as Lamu into powerful nodes of trade and civilisation. Coral stones symbolise the aspiration to be part of the civilisational order of urban Islam, as art historian Prita Meier has shown. They perpetuate the celebratory narrative of Lamu Island as a stone town. However, they also evoke the painful legacy of plantation slavery.

"Coral stone masonry encapsulates political and social tensions, embodying both the violent racial histories of dispossession and the celebratory narratives of belonging to an ecosystem."

Examining building exclusively through the lens of architecture or development today falls short of capturing these profound historical and political complexities.

Reaching Maweni

The commute from Lamu to Maweni begins with a 20-25-minute journey aboard a public boat to Manda Island. From there, the trip then involves a 15-minute ride on the back of a motorbike (known as piki piki). Often, three people share a single motorcycle, navigating muddy and rugged roads that have not been renewed in decades. During rainy days, these roads become treacherous, necessitating slower speeds and an increase in the cost of the ride.

Including waiting times, the journey from Lamu Island to Maweni takes an hour or two, with a total cost ranging between 600 and 800KSH. This overland route is slower but cheaper than going by boat. However, for residents working in Manda Maweni who earn just 1000KSH on a good day, leaving Maweni often means saving up their daily pay for weeks or even months.

Most tourists know Manda Island because this is where the airport is located. Just a few kilometers away, however, the village of Maweni remains a highly marginalized space where quarry workers remain bound to backbreaking labour and have limited mobility options due to high transportation costs.

Nevertheless, material circulates at a frantic pace. Material from the quarrying sites is transported to the shore via donkeys and carts. From there, workers carry the materials on their shoulders onto the boat, which then ferry them to the seafront of Lamu Town.

And just as coral stones are carried out of the village, water containers are carried in. The island has no source of drinking water. Cyclists are often seen transporting yellow water containers brought from Lamu Island. Drinking water makes up a significant portion of household expenses in Maweni.

Mining and Blackness

Minerals are commonly perceived as inert matter available for exploitation and activation. The logic of extraction and the language used to describe geological processes pervade the experiences of those involved in mining. Geographer Kathryn Yussof has argued that the extraction and commodification of mineral material goes hand in hand with colonial logics of dehumanization. This process is intricately tied to the racialisation of bodies, as the categorisation of blackness is a prerequisite for extracting resources from colonised territories.

Blackness is closely linked to the formation of a subjectivity intentionally distorted by the logic that the violence inherent in resource extraction must be absorbed by black bodies. Blackness, furthermore, is an embodied experience, manifesting itself in journeys and interactions, characterised by the constant movement of bodies, memories, and cultures. These populations possess the capacity to evolve and adapt, "to become different things at different times," reflecting an urban population in perpetual motion or considered available for movement," as urbanist Abdoumaliq Simone writes.

"The concept of Blackness assumes a relational character in Maweni, pertaining to individuals perceived as "immigrants" (colloquially "up-country people") rather than indigenous residents in the local politics of Lamu."

Ecologies of belonging #2302

Fixators of oppression in space

2023

Cristina De Lucas

Download PDF

Cristina De Lucas

Download PDF

This paper aims to shed light on the connections between property, belonging, and power dynamics in Lamu, Kenya. It relates the historical and conceptual foundations of property to the role of emotions and social negotiation in the construction of belonging. By exploring this interplay between land and belonging, the paper aims to gain a deeper understanding of social hierarchies and identity in Lamu.

Property can be conceptualised as a potent instrument of power, driven by the act of possession akin to domination, thereby ensuring the perpetuation of oppression. Moreover, belonging can be understood as a profound sense of comfort and the emotional responses derived from a harmonious alignment with one's surroundings in terms of behavioural constraints, which are influenced by the directives imposed by a dominant authority. This parallel can be drawn to apprehensions regarding discrimination and exclusion.

Lamu is a vibrant and heterogeneous place characterised by diverse ethnicities, religions, and cultures. With a blend of Islam and Christianity, the region features a fusion of traditions and beliefs. However, despite its rich cultural heritage, Lamu often finds itself stigmatised by Kenya as "the poor, undeveloped one." This discrimination stems from prevailing narratives that undermine the economic and social progress of the area. Additionally, Lamu bears the lasting consequences of British colonisation, having inherited a foreign system of governance that continues to influence its present-day development.

Property can be conceptualised as a potent instrument of power, driven by the act of possession akin to domination, thereby ensuring the perpetuation of oppression. Moreover, belonging can be understood as a profound sense of comfort and the emotional responses derived from a harmonious alignment with one's surroundings in terms of behavioural constraints, which are influenced by the directives imposed by a dominant authority. This parallel can be drawn to apprehensions regarding discrimination and exclusion.

Lamu is a vibrant and heterogeneous place characterised by diverse ethnicities, religions, and cultures. With a blend of Islam and Christianity, the region features a fusion of traditions and beliefs. However, despite its rich cultural heritage, Lamu often finds itself stigmatised by Kenya as "the poor, undeveloped one." This discrimination stems from prevailing narratives that undermine the economic and social progress of the area. Additionally, Lamu bears the lasting consequences of British colonisation, having inherited a foreign system of governance that continues to influence its present-day development.

“Traditionally, the indigenous peoples of Lamu lived in tightly-knit communities where a council of elders played a central role in decision-making processes.”

These respected figures were responsible for ensuring the community's well-being, managing land usage, maintaining security, and overseeing trade activities. They also presided over civil disputes among neighbours and conducted annual religious rituals, many closely tied to economic practices such as farming, livestock rearing, and fishing.

However, the current administrative structure of the government, particularly the presence of the provincial administration, conflicts with these traditional modes of rule.

Consequently, some communities in Lamu have strained relationships with these appointed leaders, resulting in a lack of effective representation and limited opportunities for community participation in decision-making processes. It is within these contexts that housing construction, property dynamics, and the formation of social belonging become salient factors that both influence and are influenced by Lamu's broader power structures.

However, the current administrative structure of the government, particularly the presence of the provincial administration, conflicts with these traditional modes of rule.

“Chiefs, sub-chiefs, and headmen appointed by the government now handle most disputes, effectively sidelining the authority of the Council of Elders. This erosion of power has led to a loss of the indigenous peoples' sense of prior informed consent, as the government-appointed local leaders often fail to consult with the communities they are meant to represent.”

Consequently, some communities in Lamu have strained relationships with these appointed leaders, resulting in a lack of effective representation and limited opportunities for community participation in decision-making processes. It is within these contexts that housing construction, property dynamics, and the formation of social belonging become salient factors that both influence and are influenced by Lamu's broader power structures.

A disenchanted home

As we delve into the exploration of property as an instrument of power, navigating the realm of belonging becomes essential—a concept intricately intertwined with the transmission of narratives surrounding cultural identity. Belonging encompasses the multifaceted tapestry of connections, attachments, and associations individuals forge with spaces, objects, and communities. Within this framework, we can discern how emotional motivations traverse the landscape of property relations.

Scholar Nira Yuval-Davis defines belonging as "an emotional (or even ontological) attachment about feeling 'at home', understood as a safe space." She attests that belonging is always a dynamic process, not a reified fixity, arguing that the latter is only a naturalised construction of a particular hegemonic form of power relations.

However, the feeling of belonging also exists in relation to fixed factors such as family and social roles. These are not only emotional attachments but also structures of power.

“Romanticising the role of belonging as solely an emotional attachment to childhood memories diminishes the power dynamics at play.”

While it is true that emotional attachments to memories become more pronounced when one is distanced, this heightened visibility results from confronting the feeling of not belonging. These sentiments merely reflect the social comfort of knowing that one's values align with the prevailing social norms of the surroundings.

Communal, state, and private property

In Lamu, the dynamics of land ownership are shaped by a complex interplay of cultural, historical, and political factors. The local population, who predominantly practice Islam, strongly advocates for preserving traditional system of ownership, governed by councils of elders.

The elders hold the power to allocate land use but not ownership. However, the authority of the elders extends beyond land, as they also make decisions pertaining to security trade and oversee annual religious rituals.

However, the administrative structure imposed by the government, particularly through the presence of the provincial administration, means a centralization of power. This shift has resulted in a sense of detachment amongst the people and lack of transparency and accountability in government.

“The Kenyan government's categorisation of land as Government Land has been exploited by the political and financial elite to gain access to ancestral lands, branding the indigenous communities as ‘squatters’ on their territories.”

A significant portion of Lamu's land, however, is recognised as "community land," intended for communal use and livelihoods. To protect these communal lands, regulations stipulate that they should be held by communities identified based on ethnicity, culture, or similar community interests. Within the community, families and individuals are allocated rights to use the land in perpetuity, with the ultimate ownership vested in the community.

The dynamics of land ownership in Lamu reflect the tension between traditional governance systems, the imposition of colonial structures, the influence of political and financial elites, and the ongoing struggle to protect communal land and livelihoods from land grabbing.

Maritime mobilities

How does the construction of the new port disrupt maritime mobility patterns and marine-based livelihoods? What interventions will be needed to safeguard these for the future, and which new livelihoods might emerge?

The new regime of mobility which the LAPSSET project aims to establish disrupts existing maritime livelihoods and mobility across the Lamu region. Sustained civil society action has resulted in a one-time, highly contested compensation scheme for fisherfolk. But many in the community are aware that this compensation does little to guarantee locals’ inclusion in economic development, nor mitigate the risks and threats to existing way of life.

Meanwhile, anxiety about the future of Lamu is prompted by rumours about a new bridge and ferry connections and fears about the closure of the dug-out channel that facilitates crucial east-west travel in the archipelago.

Meanwhile, anxiety about the future of Lamu is prompted by rumours about a new bridge and ferry connections and fears about the closure of the dug-out channel that facilitates crucial east-west travel in the archipelago.

Through ethnography and mapping, our work explores the relationships between the ways people move across the archipelago and their ability to sustain themselves. It shows how mangrove, fishing, and tourist livelihoods depend on maritime movement, shaped by the intricacies of tides, seasons, and state security. Following diverse narratives from different groups of people, the research addresses the tension between hopes for a prosperous future and fears of losing livelihoods.

Projects

Maritime mobilities #2304

A Port of Splintered Promise

Mokowe/Lamu/Pate, 2023

Munib Rehman

Download PDF

Munib Rehman

Download PDF

“These people”

We arrive in the early hours of dawn and dock at the main jetty of Mokowe, Lamu County’s first mainland town west of the archipelago. From Lamu town, the commute takes a mere 15 minutes, and one does not have to wait long for the boat to garner the dozen or so passengers it needs to make the journey worth the captain’s while. Traffic commences early on this most frequented of thoroughfares, as the movement of cargo, schoolchildren, and government functionaries underlies the island’s dependence on mainland supplies and infrastructure.

Morning cargo on the shore of Mokowe Jetty

One is greeted by heaps of cargo littered about the place, waiting to be loaded onto cargo boats embarking back towards various stations within the Island network. A procession of porters animates the scene, transferring merchandise between lorries and cargo ships. On-land conveyance awaits further on from the slope of the shore, with vans and buses idling alongside private-hire estate cars and motorbikes.

Porters at Mokowe

A porter frantically waves at us from afar, taking exception to our filming of the spectacle. The man walks up to interrogate our objectification of their drudgery and is unusually verbose for his occupation, asking if we thought they were “imbeciles”. Courtesy obliged us to concede to his protests all too willingly, but the man seemed to relish this break from his labour and continued conversing in practiced English.

We arrive in the early hours of dawn and dock at the main jetty of Mokowe, Lamu County’s first mainland town west of the archipelago. From Lamu town, the commute takes a mere 15 minutes, and one does not have to wait long for the boat to garner the dozen or so passengers it needs to make the journey worth the captain’s while. Traffic commences early on this most frequented of thoroughfares, as the movement of cargo, schoolchildren, and government functionaries underlies the island’s dependence on mainland supplies and infrastructure.

Morning cargo on the shore of Mokowe Jetty

One is greeted by heaps of cargo littered about the place, waiting to be loaded onto cargo boats embarking back towards various stations within the Island network. A procession of porters animates the scene, transferring merchandise between lorries and cargo ships. On-land conveyance awaits further on from the slope of the shore, with vans and buses idling alongside private-hire estate cars and motorbikes.

Porters at Mokowe

A porter frantically waves at us from afar, taking exception to our filming of the spectacle. The man walks up to interrogate our objectification of their drudgery and is unusually verbose for his occupation, asking if we thought they were “imbeciles”. Courtesy obliged us to concede to his protests all too willingly, but the man seemed to relish this break from his labour and continued conversing in practiced English.

We talked of his occupational hazards, and he went through a litany of accidents they had grown accustomed to, including overloading, capsizing, and even fires. Soon this turned towards what the future held, which gave us a segue to mention the prospect of a rumoured bridge between Lamu town and the mainland. This was seen as part of the infrastructural upgradation that LAPSSET brought to the region, and would seemingly streamline the daily commute of many.

However, this proposition was met with a patient sigh, followed by a rather resigned explanation of why this prospect, real as it was, could not materialise. A plan for the bridge was indeed proposed, but the local boatsmen vehemently protested against such inconsiderate benevolence, seeing as a land connection would spell an end to their means of livelihood. Excluding himself as a Kikuyu mainlander, he decried the siege mentality of the islanders:

“They feel like the main government is working with the Chinese, and the Swahili people are kind of just pushed aside. I remember the Chinese proposed to construct the bridge very well – they even came with a map… but these Swahili from Lamu refused it. The main reason is that the bridge would deny them jobs.”

“These people… they don’t like change, they don’t like development, they want the same of what they have – that is why they are against such projects.”

This political rift, mapped onto ethnic difference, has been central to Lamu’s relationship with the national government.

Coastal communities tend to look back on the Omani maritime empire as a period of prosperity for Lamu, in contrast to the marginalization of the region since Kenyan independence. Kikuyu communities arguably bore the brunt of colonial oppression during British rule, and their anti-colonial resistance is foundational to Kenyan independence and post-independence nation-building. However, Kikuyu political elites, with president Jomo Kenyatta at the top, are also widely described as the biggest landgrabbers of Kenya, responsible for the country’s neo-colonial injustices after independence.

Mirroring the feelings of marginalisation the porter felt in Bajuni-led Lamu, this complex history inhabits contemporary politics and social dynamics. Coastal communities are wary of state impositions from Kikuyu and other “upcountry Kenyan functionaries, of local real-estate speculation by their investment-savvy middle class, and of the mainland’s vague but consequential conflation of Al-Shabaab with the local community.

The porter occupied us for a rather generous half hour, before we realised he was holding out for some renumeration for his time. This made us realise how little of his exposition depended on our prompts, and why it had all seemed rather rehearsed. Well-meaning wazungu were to be sold a story, or so it seemed.

Infrastructure as a frame of analysis

While the LAPSSET infrastructure project served as both topic and context in our research, we were also inspired to mobilize infrastructure as an analytical lens. By virtue of the vastness of its purview, and the indeterminacy of the boundaries of its causal and effectual spheres of influence, infrastructure evades disciplinary caging. It does however lend itself quite naturally as a site of inquiry to a diversity of social science disciplines such as anthropology, history, human geography, urban studies, and science and technology studies. Each of these offer approaches that addresss particular aspects of such a boundless chain of phenomena.

In short, the challenge confronted by a researcher is first and foremost of delimitation; a matter of honing in on a case through a selection of methods, and then framing it within spatial, social, and temporal constraints.

Ethnographic imprecision

In order to grapple with the effects of the LAPSSET project spread across such a spatially dispersed area - and to accommodate the nebulous phase this inquiry finds itself in - this undertaking calls for a lenient imprecision in its ethnographic approach. The aim here is to document social attitudes, responses and expectations around the construction of the port.

As Hannah Knox and Penny Harvey summarised the challenge of such a premise, “when studying infrastructure the anthropologist must confront the problem of locating an ethnographic site without limiting the scale of description.”

As Hannah Knox and Penny Harvey summarised the challenge of such a premise, “when studying infrastructure the anthropologist must confront the problem of locating an ethnographic site without limiting the scale of description.”

Following suit, this study aims to take account of the variety and instability of human relations in the shift brought about by this infrastructural intervention within the community, and attempts to offer a snapshot of the social and cultural dynamics of change brought about by the port.

Imaginaries of development

To envisage infrastructure within a public imaginary is to dwell on an aesthetic plane of conception. Framing infrastructure as such relegates its technical function to a separate, secondary concern; the priority instead being the imaginative potential of its image. This implies not only the visuality of the spectacle itself, but also the sense in which it is internalised by its addressees.

Brian Larkin offers a masterful exposition of this potential, pushing back against the trope of ‘infra’ as denoting something hidden and behind the scenes. To be fair, the notion of an out-of-sight network of processes, one that enables the end-user a certain convenience through an unassuming interface, does provide an inexhaustible avenue of research. But Larkin argues that there is no end to the relational webs that one may consider in trying to come to grips with infrastructure, and emphatically states that “discussing infrastructure is a categorical act… a moment of tearing into those heterogeneous networks to define which aspect of which network is to be discussed.”

Drawing license from the clarity of Larkin's declaration, this inquiry’s categorical concern is the connotative baggage of new Lamu port within the local community. Though having enjoyed centuries of prominence as a thriving port city in past regimes, there is a palpable sense of modernity’s belated arrival that the new port announces in the current, Kenyan iteration of Lamu. A “game-changer” as it is so tritely brandished in official pronouncements, the port is held up as Lamu’s fast track ticket to development.

Such proclamations by government officials imply a tacit admission of feeling left behind so far, and speak of a motivating disjunction sorely felt between Lamu’s as-is, and its desired to-be. The trope of the port as a game-changer therefore is not without conviction, and is emblematic of the “postcolonial state’s imaginative investment in technology,” dissonant as it might be with the heritage-tinged, donkey-cart romance of Lamu’s Old Town.

“As a regional gateway to the riches of East Africa, Lamu has the chance to shed its image of a developmental hinterland for a new prominence on the international stage. The proposed LAPSSET project will immensely contribute to the opening up of the County externally to other Port Cities and Nations of the world.”

Such proclamations by government officials imply a tacit admission of feeling left behind so far, and speak of a motivating disjunction sorely felt between Lamu’s as-is, and its desired to-be. The trope of the port as a game-changer therefore is not without conviction, and is emblematic of the “postcolonial state’s imaginative investment in technology,” dissonant as it might be with the heritage-tinged, donkey-cart romance of Lamu’s Old Town.

Maritime mobilities #2303

The role of maritime mobility in sustaining livelihoods within the Lamu Archipelago

Tides of Change

The role of maritime mobility in sustaining livelihoods within the Lamu Archipelago

Lamu archipelago, 2023

Tanja Meier

Download PDF

Tanja Meier

Download PDF

"The place they chose to build LAPSSET port is dangerous. Because if the Mkanda channel is closed, Lamu will be finished."

This is how Mohammad Mbwana - Shungwaya Welfare Association chairman and a local historian - expressed his fear for Lamu's future in our interview. According to Mbwana, disruptions to maritime mobility will be the end of Lamu. The infrastructural development in Lamu is anticipated with both a sense of promise and violence. The government promises growth, modernity, and prosperity for the region against a background of dispossession, displacement, and exclusion.

Lamu County is the northernmost county on the Kenyan coast. It borders Somalia and has direct access to the Indian Ocean. The locals do not perceive this ocean as a border but rather as an extension of the land and life around the islands. Many indigenous communities inhabit the Lamu archipelago. Their cultural identity depends on the natural resources surrounding the archipelago.

Water is of paramount importance, serving as a base for both the fishing industry and mangrove management, two primary means of livelihood within the island network. The sea is often overseen as an environment where people navigate and manoeuvre. However, maritime societies constantly interact between land and sea, and these connections shape their knowledge and practices. Simultaneously, littoral communities, such as the inhabitants of Lamu, are connected to their hinterlands socially, politically, and economically.

LAPSSET may create new markets for Kenya and the region through which state income can be generated. However, these ambitions turn into infrastructural violence around Lamu port, with severe ramifications for various social groups in the wider region.

LAPSSET may create new markets for Kenya and the region through which state income can be generated. However, these ambitions turn into infrastructural violence around Lamu port, with severe ramifications for various social groups in the wider region.

Honing in on transport

Literature on LAPSSET has focused on the social upheaval accompanying infrastructure, touching upon events of land grabbing, fishing bans, monetary compensations, and other processes that animate analysis on a more local scale.

However, within the broad purview of analysing such a massive international project, the disruption of regional maritime mobility has thus far evaded scholarly analysis.

Given a considerable part of the archipelago experience is commuting by boat, we saw this as an opening to inquire further on a topic that suited the limitations of our fieldwork. We thus honed in on maritime mobility and began by questioning the numerous claims on Lamu’s waterways.

How is Lamu’s maritime mobility disrupted by the ongoing port development?

What effects does this have on livelihoods and the movement within the Lamu Archipelago?

What alternatives, promises, and opportunities emerge to safeguard the future of Lamu’s current livelihoods?

Building up to Mkanda

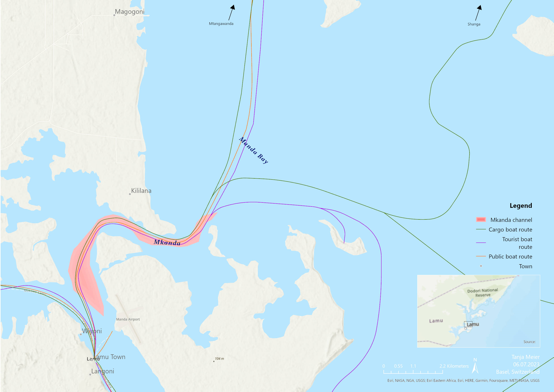

Mkanda is a channel that connects Lamu East with Lamu West. It drastically shortens the commute between islands and provides a calm, secure alternative to the outer seas. The canal cuts through the mangroves between the mainland and Manda Island.

In the 19th century, the maritime economy of the archipelago was dominated by British colonial rule. After independence, the Kenyan state took control of regulating trade.

“In 1978, mangrove harvesting and export to the Middle East was banned, forcing boat captains to resort to other occupations, such as being tour guides. In this and other ways, government involvment fueled the economic decline of the region.”

Before this curtailment of trade, large dhowscrossed the outer sea and sailed around the Lamu Archipelago and

![]() Satellite image of Mkanda channel and Wiyoni town on the bottom left corner

Satellite image of Mkanda channel and Wiyoni town on the bottom left corner

According to fisherfolk, the government-funded dredging of Mkanda in 2000 countered local economic decline and allowed small motor boats to navigate safely within the archipelago. Some people argue that the channel was dug to improve the archipelago’s security, while others interpret it as a preliminary to the planning of the Port. Furthermore, dredging led to an accumulation of sand on Amu, expanding the island with additional land for the upcoming town of Wiyoni. The exact motives behind the government-funded dredging are unclear; thus, it is hard to distinguish fulfilled objectives from fortuitous side effects. Nonetheless, the channel’s importance to various demographics is undeniable.

The construction of Mkanda also reorganised Pate Island. As historical influences of trade across the Indian Ocean shaped Lamu’s urban architecture, coastal villages were initially oriented towards the outer sea. However, since the monopolisation of the trans-oceanic trade, small towns are no longer beneficiaries of this trade. This also forces towns to re-orient themselves according to the contemporary economic situation of the archipelago.

In the 19th century, the maritime economy of the archipelago was dominated by British colonial rule. After independence, the Kenyan state took control of regulating trade.

“In 1978, mangrove harvesting and export to the Middle East was banned, forcing boat captains to resort to other occupations, such as being tour guides. In this and other ways, government involvment fueled the economic decline of the region.”

Before this curtailment of trade, large dhowscrossed the outer sea and sailed around the Lamu Archipelago and

across the Indian Ocean.

The maritime economy was then gradually replaced by steamboats operating between British India and East Africa. Today, mostly small boats circulate the island - and captains keep from the outer seas too hazardous to navigate. Satellite image of Mkanda channel and Wiyoni town on the bottom left corner

Satellite image of Mkanda channel and Wiyoni town on the bottom left cornerAccording to fisherfolk, the government-funded dredging of Mkanda in 2000 countered local economic decline and allowed small motor boats to navigate safely within the archipelago. Some people argue that the channel was dug to improve the archipelago’s security, while others interpret it as a preliminary to the planning of the Port. Furthermore, dredging led to an accumulation of sand on Amu, expanding the island with additional land for the upcoming town of Wiyoni. The exact motives behind the government-funded dredging are unclear; thus, it is hard to distinguish fulfilled objectives from fortuitous side effects. Nonetheless, the channel’s importance to various demographics is undeniable.

The construction of Mkanda also reorganised Pate Island. As historical influences of trade across the Indian Ocean shaped Lamu’s urban architecture, coastal villages were initially oriented towards the outer sea. However, since the monopolisation of the trans-oceanic trade, small towns are no longer beneficiaries of this trade. This also forces towns to re-orient themselves according to the contemporary economic situation of the archipelago.

Previously - when the island was still oriented towards the outer sea - places like Shanga and Kizingitini were the main docking places on Pate Island. Now, though, Mtangawanda is the island's main dock, easily accessible as it is through the channel from Amu and the mainland.

Routes going through Mkanda connecting Amu with Pate Island (Mtangawanda & Shanga)

Today, Mkanda is a highly frequented water passage for cargo, tourists, and public transport. Using the channel to commute between Lamu East and Lamu West saves travel time and reduces fuel costs against the sea route. Moreover, Mkanda is crucial for Lamu's fishermen to operate all year round and avoid dangerous voyages into the outer sea.

"For the route of Shela (outer sea) - it is seasonal. When the sea is rough, they use the Mkanda fishing route," explains BMU Amu Chairman.

The Mkanda channel is especially important during the rainy season when the sea picks up, and the route through the outer sea becomes dangerous and impassable for small boats. "So, most of the time, when the sea picks up, we try to advise them not to cross there [the outer sea]. The channel is more on this side [inside the archipelago]. So, we try fishing within here," explains the chairman.

Lamu Port from Mkanda

Lamu Port from MkandaAlthough Mkanda is at the centre of the archipelago, many other waterways are highly important. Map 5 displays some of the leading maritime routes that are used regularly. The map shows that maritime routes in the Lamu Archipelago are not only used by fisherfolk but are crucial to other activities such as mangrove cutting, cargo shipping, public transportation, and NGO projects.

Main waterways on Lamu Archipelago

The Goliath of global trade

Manda Bay was chosen for the construction of the new port because of its natural geography. The deep sea level here allows several large ships to dock and manoeuvre in the port area simultaneously, which is supposed to facilitate large-scale trade.

Most aspects of the new projects are financed through public-private partnership (PPP), making negotiations complicated. Within this framework, Kenya’s government can contribute by providing land and other investments and profit from the share in (tax)-revenues. Such neo-colonial invitations are not new to the continent. Foreign investors and companies are the primary beneficiaries of the project. Officials are quick to emphasise, however, that this also offers new opportunities for the middle class:

Most aspects of the new projects are financed through public-private partnership (PPP), making negotiations complicated. Within this framework, Kenya’s government can contribute by providing land and other investments and profit from the share in (tax)-revenues. Such neo-colonial invitations are not new to the continent. Foreign investors and companies are the primary beneficiaries of the project. Officials are quick to emphasise, however, that this also offers new opportunities for the middle class:

“You know, Hindi – people have taken land for speculation. Because Hindi is where the project is, and people anticipate it. People know that Hindi will be another place like Dubai in the next 10-20 years.”

The adverse effects of the project are manifold. Environmental concerns and loss of existing livelihoods resulted in various protests and community outcries in Lamu. Coalitions such as Save Lamu understand the community’s worry about the destruction of mangroves and corals and, therefore, the threat to the environment and the livelihoods of Lamu. People are not entirely opposed to LAPSSET but disagree with its violent and exclusionary implementation, with claims of unequal distribution and benefits not being solved.

The port also raises new questions about logistics, ownership and access in Lamu. Increased security measures and the intensified flow of commodities shape transportation patterns. This overlooks local concerns and redirects the focus to a more global economy. It also reconfigures possession and blurs the boundaries of the origin of goods. Moreover, the question of locating accountability becomes more obscure.

The port also raises new questions about logistics, ownership and access in Lamu. Increased security measures and the intensified flow of commodities shape transportation patterns. This overlooks local concerns and redirects the focus to a more global economy. It also reconfigures possession and blurs the boundaries of the origin of goods. Moreover, the question of locating accountability becomes more obscure.

Expected change in maritime routes

The County Integrated Development Plan 2023-2027 emphasises large-scale growth in terms of mobility on land and marine. Highways connecting Lamu to the broader region and the port connecting Lamu - and, more broadly, East Africa - to the Indian Ocean disrupts existing mobility patterns. How these patterns may change in the future is a matter of contestation today.

The plan identifies the provision of land for industrial development, but it does not specify future land usage. However, it does anticipate the development a spatial plan in the coming years.

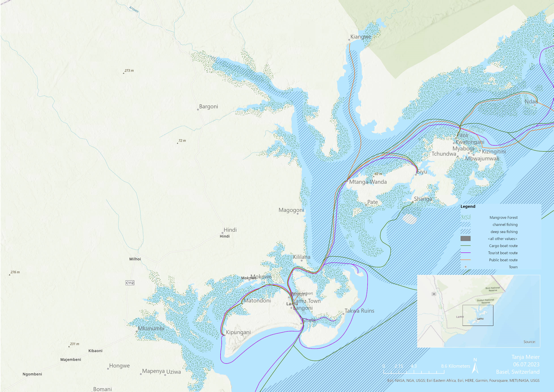

Seasons, tides, towns, and natural resources influence current mobility patterns in the Lamu archipelago. The map below shows the most frequent waterways on the archipelago and the fishing areas and mangroves around the port area.

![]() Mobility patterns and marine livelihood zones around the port area

Mobility patterns and marine livelihood zones around the port area

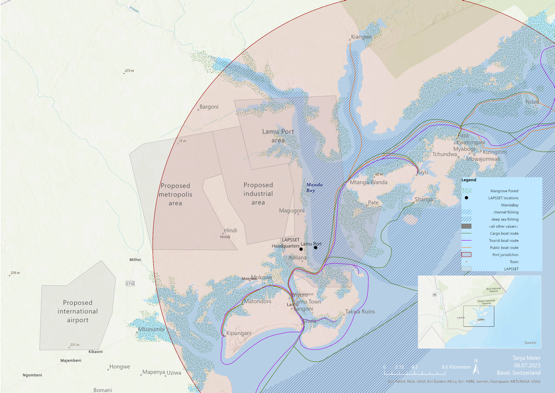

The map below shows the extent of Lamu Port and future development areas. These areas will shift the balance of development to the mainland and affect maritime mobility patterns.

![]() LAPSSET growth areas, existing waterways and marine livelihood areas

LAPSSET growth areas, existing waterways and marine livelihood areas

The plan identifies the provision of land for industrial development, but it does not specify future land usage. However, it does anticipate the development a spatial plan in the coming years.

Seasons, tides, towns, and natural resources influence current mobility patterns in the Lamu archipelago. The map below shows the most frequent waterways on the archipelago and the fishing areas and mangroves around the port area.

Mobility patterns and marine livelihood zones around the port area

Mobility patterns and marine livelihood zones around the port areaThe map below shows the extent of Lamu Port and future development areas. These areas will shift the balance of development to the mainland and affect maritime mobility patterns.

“The establishment of the port may make the existing route via the Mkanda channel unviable. As a result of the LAPSSET implementation, these routes are therefore at the centre of anxiety about the future of the region.”

LAPSSET growth areas, existing waterways and marine livelihood areas

LAPSSET growth areas, existing waterways and marine livelihood areasThe plan stress the establishment of highways, as well as new towns and commerce centres on the mainland. The focus lies on a solid road network connecting Lamu Port to other parts of Kenya, South Sudan, and Ethiopia.

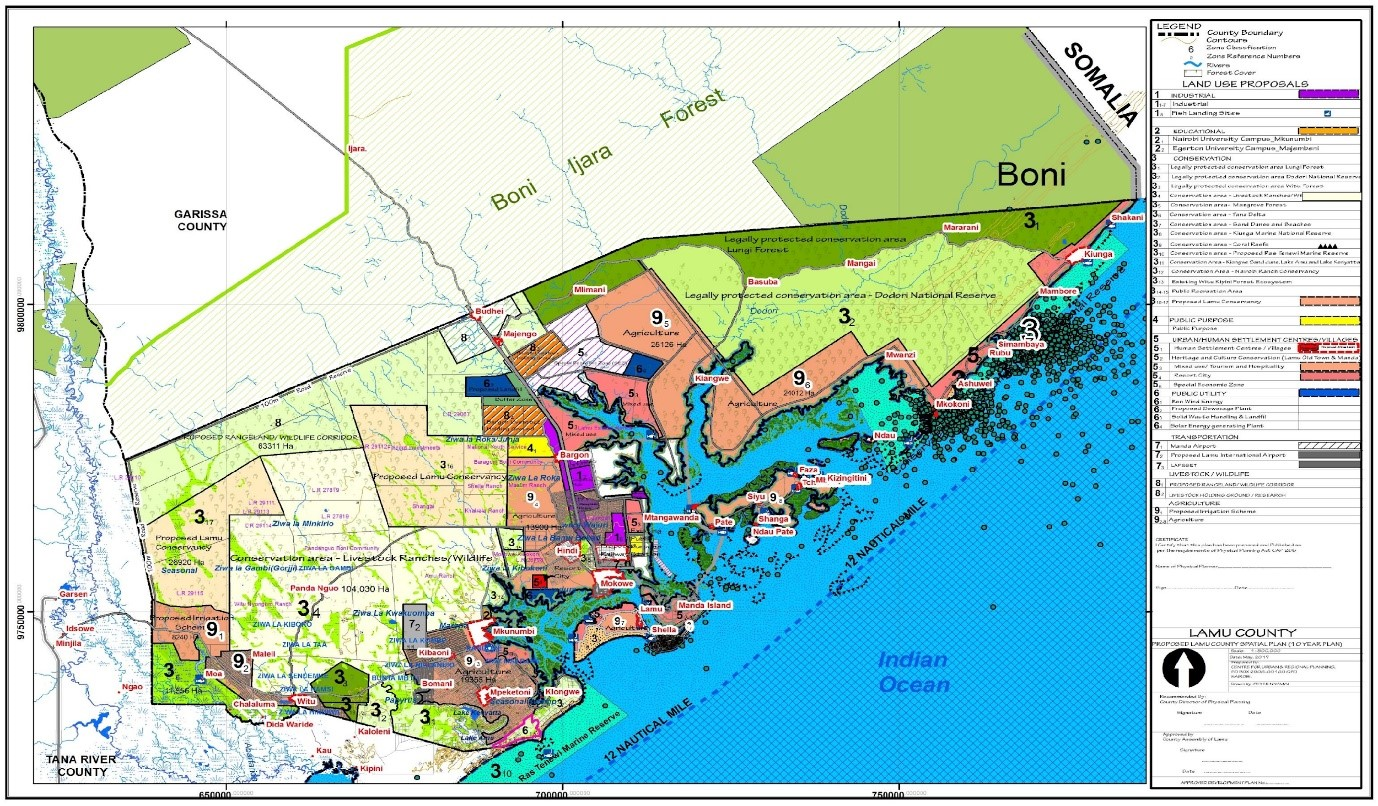

![]()

County Spatial Plan (by The County Government of Lamu, 2023)

Once the port is fully operational, access to existing waterways might change, and small-scale boating may face more significant restrictions, as the new port prioritises large cargo ships.

The fear of losing personal investments in small-scale livelihoods is shared among many residents. However, the shift from small-scale livelihoods that provide individual incomes to a large-scale port industry is undoubtedly expected to bring changes in the maritime mobility and the livelihoods on the Lamu archipelago.

Despite the expectations and fears, what remains unanswered is whether the promise of modernisation leaves room for small-scale maritime livelihoods in the future.

![]() Cargo boats docking at Lamu Port

Cargo boats docking at Lamu Port

County Spatial Plan (by The County Government of Lamu, 2023)

Once the port is fully operational, access to existing waterways might change, and small-scale boating may face more significant restrictions, as the new port prioritises large cargo ships.

The fear of losing personal investments in small-scale livelihoods is shared among many residents. However, the shift from small-scale livelihoods that provide individual incomes to a large-scale port industry is undoubtedly expected to bring changes in the maritime mobility and the livelihoods on the Lamu archipelago.

Despite the expectations and fears, what remains unanswered is whether the promise of modernisation leaves room for small-scale maritime livelihoods in the future.

Cargo boats docking at Lamu Port

Cargo boats docking at Lamu PortHow are memories of displacement and hopes of return shared in Lamu? How do they impact political claims to address historical and ongoing injustices?

The streets and walls of Lamu town resonate with the collective memory of displacement—etched deeply in the community. Following the Shifta War, a secessionist conflict held in northeastern Kenya between 1963 and 1967, thousands of people who had to flee due to extreme violence found refuge and stability in Lamu. Neighbourhoods like Langoni and Gadeni emerged in part as a result of this influx, and have become living archives of the hopes and struggles of the displaced.

In the face of LAPSSET's promise of infrastructure-led development, these memories of displacement and forced resettlement are reactivated and reworked. This theme explores the urban afterlives of displacement by focusing on the memories and experiences of those affected by displacement.

Projects

Urban stories of Displacement #2305

Nyumbani ni Nyumbani

(Home is Home)

Short film

Authors Amina Omar

Hajj Shee

Florence Alder

Isabella Pamplona

Hajj Shee

Florence Alder

Isabella Pamplona

Lamu, 2023

Watch complete film

Watch complete film

Many internally displaced persons who fled the mainland during the Shifta War live in Lamu town, particularly in the urban areas of Gadeni and Langoni. This project shows how displaced communities grapple with belonging and with political claims to historical redress.

"Nymbani ni Nymbani" is based on a series of life story interviews and urban walks with IDPs and their family members of different generations who currently reside in Lamu.

The film gives voice to these families and community leaders at the forefront of political struggles for reparations and portrays how they contributed to make Lamu what it is today.

_

Produced by:

Isabella Pamplona, Florence Alder, Amina Omar and Hajj She.

Starring:

Mohammed Mbwana, Ahmed Kihobe, Hassan Awadh, Esha Adi, Esha Adi's aunt, Mwana Amina Amin, Mohamed Ali and Omar Shamina.

Language:

English and Kiswahili

"Nymbani ni Nymbani" is based on a series of life story interviews and urban walks with IDPs and their family members of different generations who currently reside in Lamu.

The film gives voice to these families and community leaders at the forefront of political struggles for reparations and portrays how they contributed to make Lamu what it is today.

_

Produced by:

Isabella Pamplona, Florence Alder, Amina Omar and Hajj She.

Starring:

Mohammed Mbwana, Ahmed Kihobe, Hassan Awadh, Esha Adi, Esha Adi's aunt, Mwana Amina Amin, Mohamed Ali and Omar Shamina.

Language:

English and Kiswahili

Urban stories of Displacement #2306

Displacement and Belonging in Lamu's Archipelago

Where is home?

Displacement and Belonging in Lamu's Archipelago

Lamu Island/Pate Island, 2023

Florence Alder

Isabella Pamplona

Download PDF

Florence Alder

Isabella Pamplona

Download PDF

"We cannot leave this place here... But we would be happy to go back there."

This quote, by a Lamu resident who identifies as an IDP, captures the complex feelings experienced by the displaced community in Lamu after their displacement from the mainland during the Shifta War. The disappointments of Kenya's post-colonial politics have left them in a kind of limbo where they do not feel full belonging to their ancestral homeland nor fully to Lamu, the place where they currently live.

“Their attachment to Lamu is intertwined with a longing for a different, parallel reality they claim as their home. In claiming to belong to their homeland, ethnicity becomes a political tool through which they exercise agency and negotiate compensation for the historical injustices suffered during the Shifta War.”

This paper investigates the nuanced sense of belonging among Lamu's IDPs in the context of urban archipelagic life. It explores how their feelings are shaped by the complex interplay between postcolonial politics, the particularities of archipelagic life, and the traumas of displacement. In doing so, it traces their relationship with land, sea, livelihoods, community, and their influence on the urban fabric. Furthermore, it shows how displacement and dissatisfaction with postcolonial Kenya inform the mobilizing of ethnicity as a political tool in seeking reparations.

Mainland ancestries

In numerous ways, IDPs and their descendants establish a sense of rootedness in their ancestral homeland. This encompasses their past lives on the mainland, emphasising the significance of agriculture, fishing, trade, and a close-knit community. It also includes the enduring connections to Lamu's land and coastal waters.

The archipelagic way of life, marked by continual movement and fluidity, shapes their perceptions of space, time, and belonging.

Settling into Lamu

Recent scholarly discussions of migration encompass broader socio-political, political-economic, and cultural processes, seeing the geopolitical dynamics of global capitalism as the ultimate cause of forced displacement. These perspectives challenge the idea that migration is purely voluntary or involuntary, considering the interplay between the factors influencing it. Within this context, the settlement of IDPs in Lamu appears as a complex process, influenced by the interplay of available possibilities and the socio-political and economic factors present.

IDPs belong to Lamu in many different ways. This is evident in their adaptive livelihood strategies, integration into the island's socioeconomic fabric, intermarriage with local communities, formation of new community organisations, and their significant impact on shaping the urban landscape. However, their connection to Lamu is not without complexity or ambiguity.

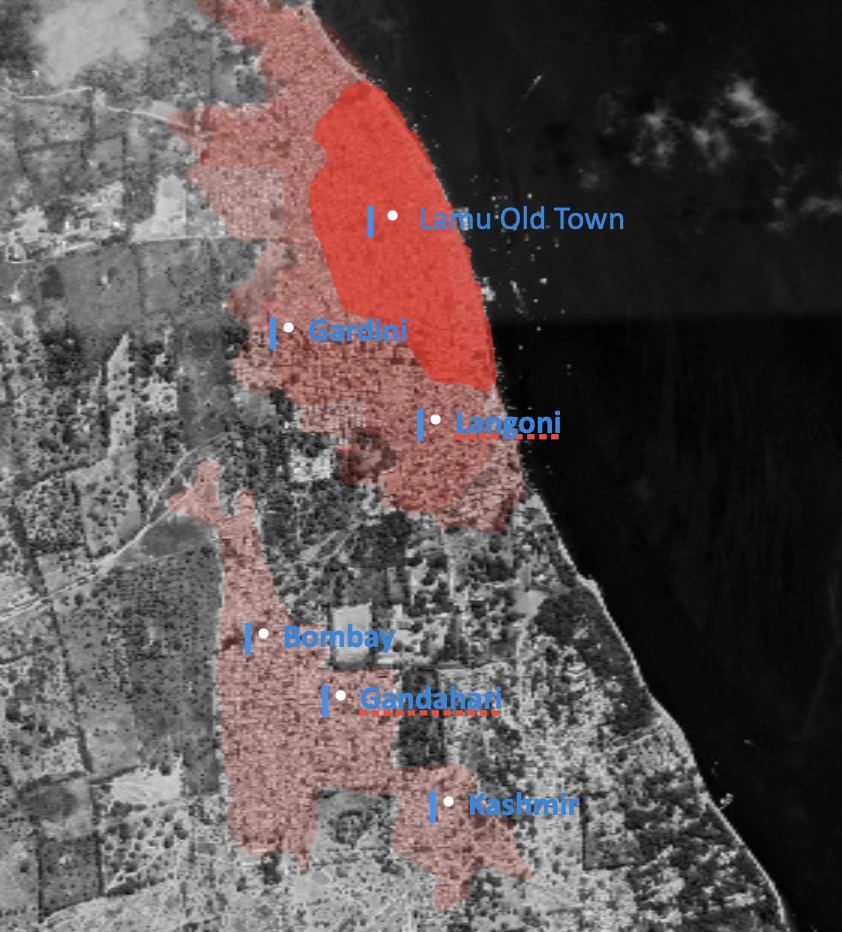

In Lamu island, the two areas generally known for hosting IDPs and "immigrants" are the Langoni and Gadeni neighbourhoods. These areas experienced significant growth during the early twentieth century, in part because of the influx of Indians. With Kenyan independence, many Indians left the island, leaving many properties unoccupied. As families and individuals displaced during the war sought refuge in Lamu, locals offered them access to housing in these neighborhoods.

The Gadeni area, which used to be located on the outskirts of the Old Town, held small farming plots with fruits and vegetables, from where Lamu locals sold their produce both in the local market and to the Middle East. This dynamic of urban farming gave the neighbourhood its name of Gadeni, which comes from "garden.” Since the area was not densely built-up back then, IDPs were given the opportunity to lease the land in the neighbourhood.

IDPs belong to Lamu in many different ways. This is evident in their adaptive livelihood strategies, integration into the island's socioeconomic fabric, intermarriage with local communities, formation of new community organisations, and their significant impact on shaping the urban landscape. However, their connection to Lamu is not without complexity or ambiguity.

IDPs continue to yearn for an imagined home, which is manifested in a sense of detachment from the local community, dedicated efforts to preserve cultural traditions, the perception of being guests in Lamu, and engagement in political activism to return to their homeland.

In Lamu island, the two areas generally known for hosting IDPs and "immigrants" are the Langoni and Gadeni neighbourhoods. These areas experienced significant growth during the early twentieth century, in part because of the influx of Indians. With Kenyan independence, many Indians left the island, leaving many properties unoccupied. As families and individuals displaced during the war sought refuge in Lamu, locals offered them access to housing in these neighborhoods.

The Gadeni area, which used to be located on the outskirts of the Old Town, held small farming plots with fruits and vegetables, from where Lamu locals sold their produce both in the local market and to the Middle East. This dynamic of urban farming gave the neighbourhood its name of Gadeni, which comes from "garden.” Since the area was not densely built-up back then, IDPs were given the opportunity to lease the land in the neighbourhood.

"They were given settlement there because they couldn't afford to rent or buy houses in town, so they got them in monthly or annual leases..."

(Kihobe, A. 2023)Settling in Gadeni gave the IDP community the opportunity to start building new lives in Lamu. Our interlocutor Ahmed Kihobe further explained that this provided a sense of security and peace for the displaced individuals, as the islands were considered safe compared to the mainland. There, they found the possibility to participate in the social life of the town. The provision of settlement and opportunities in Lamu brought a bigger influx of IDPs to the area and facilitated the reunion of dispersed families and communities. As they started to feel at ease with the possibilities in their new environment, many of the IDPs contacted others in Pate, Mtangawanga, and Shanga with the aim of bringing their relatives together again.

Settling in Lamu implied a tradeoff for IDPs in many aspects. As previously mentioned, one of the factors that weighed in when deciding to settle on the island was the possibility of access to education for future generations. In the case of Hassan, while he was only able to secure a source of income with prospects in Takwa, having access to education for his children was an essential factor that contributed to his settling and deciding to build his home in Lamu.

In the past years, being able to access education has allowed the younger generation to secure employment opportunities outside of Lamu, especially in the Middle East. Many individuals, including most of Ahmed's classmates and friends, decided to leave Lamu in pursuit of the opportunity for a better life. Ahmed highlighted that some of these friends have been absent from Lamu for almost four decades. Yet, while choosing to stay away, they still provide financial support to their families, "they will send remittance money to help their family, but they don't want to come back again.” Something worth mentioning is the contrasting situation between the children and grandchildren of IDPs. While wishing to move away, the older generation chooses to keep building and investing in the island, which starkly contrasts with many of their children, who have left young and have no intention of returning to Lamu.

The daily struggle

When walking around Lamu, one of the first things we asked was, “Where are all of the IDPs?”. To our surprise, we were told that most of them were at the main square, exactly where we were standing at that precise moment. Most of the individuals, mostly older men, sitting in this public area were IDPs waiting for any small job opportunity. Interestingly, by not actively working in the middle of a weekday, the common commentary was that they were idle. Yet, this scene reminisces older ways of engaging with the city in Lamu:

“Until about 50 years ago, sitting on one of Lamu’s baraza while sipping Arabic coffee formed the epitome of urban flair. Now it is depicted either as an outdated practice by local youth or as an example of Swahili ‘laziness’ by mainland Kenyans.”

(Hillewaert, Sarah. 2017)This everyday waiting at the main square in Lamu, while they are looking for ways of earning at least 200 KSH to make it through the day, is just one example of the many ways in which IDPs demonstrate a nuanced sense of belonging within the city. Despite their challenging circumstances, IDPs actively navigate their identities and connections to the urban space, finding ways to establish a sense of belonging. While some people actively look for new livelihoods, like walking tourists around or selling tobacco, others are still trying to preserve their traditional livelihoods.

Imaginaries of Home

IDPs construct an imaginary of home based not only on longings for a better life, but also on ancestral narratives, which are passed on through generations. Their sense of belonging is thus in tension between attachment to and detachment from Lamu, with all its aspirations and frustrations. Ethnicity in this context is mobilized as a political tool to demand rights to land and resources and to express dissatisfaction with postcolonial Kenya's politics.

The research indicates that the IDPs strive for inclusion in the local economy and society and aim to overcome their urban marginalization. Their attachment to Lamu is multifaceted, encompassing a connection to the city and the community, a longing for their imagined home, and a desire for justice.

Heritage under Transformation

How do women transform long-standing traditions of dwelling and home-building in Lamu? How does heritage matter in the context of a rapidly changing urban landscape?

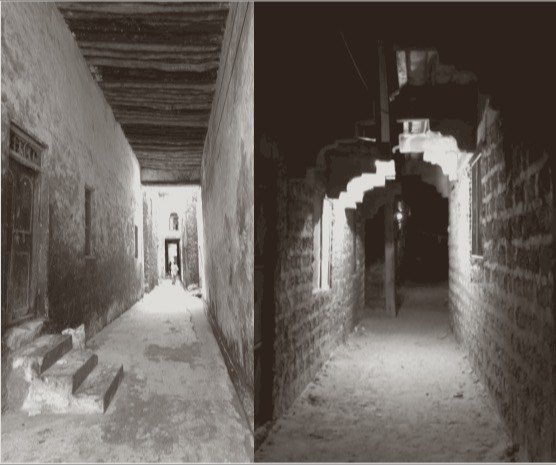

Alleys in old town (L) and new neighborhoods (Kashmir) (R)

Alleys in old town (L) and new neighborhoods (Kashmir) (R)Recognised by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, Lamu’s ancient Stone Town harbours longstanding dwelling traditions. Yet, the town has experienced fast urban growth in recent years, with the emergence of entirely new neighbourhoods built on the once-agricultural outskirts. How does the old Lamu inhabit this new Lamu? What does dwelling culture mean in this rapidly changing context?

The new homes of Lamu’s emerging neighbourhoods may still be built using coral stone and mangrove wood, but they also feature new kinds of spaces and accommodate new uses. This theme explores this ongoing transformation of domestic cultures and home-building, focusing on the roles and practices of women in Lamu’s historic town as well as its new residential neighborhoods.

The new homes of Lamu’s emerging neighbourhoods may still be built using coral stone and mangrove wood, but they also feature new kinds of spaces and accommodate new uses. This theme explores this ongoing transformation of domestic cultures and home-building, focusing on the roles and practices of women in Lamu’s historic town as well as its new residential neighborhoods.

Using semi-structured interviews and architectural methods of analysis, our research shows how women negotiate with home builders (fundi) to create domestic spaces that meet their needs even as they aim to preserve their inheritance. In doing so, we emphasise the importance of those who inhabit and transform Lamu’s built heritage. This perspective contributes to the ongoing dialogue about heritage and sustainable development in Lamu.

Projects

Heritage under Transformation

#2305

Dwelling in Transition

#2305

Dwelling in Transition

Langoni/Mkomani/Lamu, 2023

Gadsiah Ibrahim

Download PDF

Gadsiah Ibrahim

Download PDF

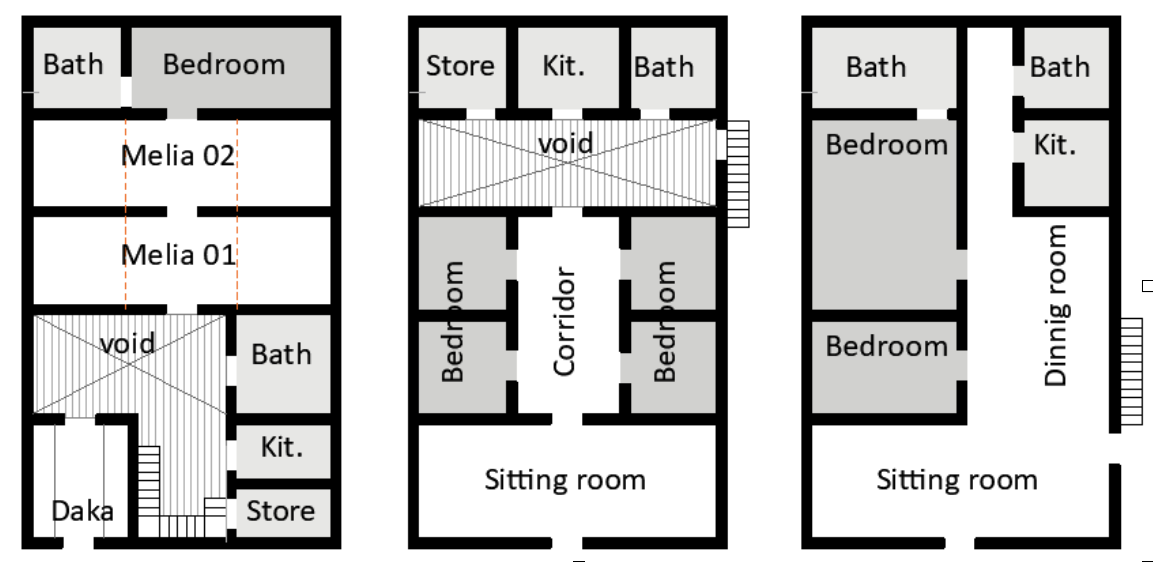

A key element of the ancient Lamu stone house is the melia setup. This sequence of rooms is characterised by a lack of clear demarcations for multiple uses, fostering the flexible uses of domectic space. The absence of assigned rooms promotes communal use, even for individuals valuing privacy within their homes.

Lamu’s famous Stone Town embraces such adaptive use. Families divide houses among themselves or repurpose the structures over time. As families grow, houses expand; multi-story structures are constructed to accommodate the increasing number of family members, reflecting the cultural tradition of mita emphasising collective living.

Lamu’s famous Stone Town embraces such adaptive use. Families divide houses among themselves or repurpose the structures over time. As families grow, houses expand; multi-story structures are constructed to accommodate the increasing number of family members, reflecting the cultural tradition of mita emphasising collective living.

Dwelling entails not just the physical structure of a house but also the profound social, cultural, and emotional connections individuals establish with their living spaces.

Women assume a central role within these spaces as primary users and decision-makers in household arrangements. Furthermore, the expertise of builders contributes to the configuration of these spaces, thus exerting a considerable influence on their design and functionality.

Recognising the cultural and historical layers embedded within these homes allows for shaping future spaces that are both culturally meaningful and sustainable over time.

The collaborative synergy between women, serving as users and decision-makers, and house builders, with their expertise, culminates in the creation of living spaces that both reflect and accommodate the unique cultural and social dynamics of Lamu.

Recognising the cultural and historical layers embedded within these homes allows for shaping future spaces that are both culturally meaningful and sustainable over time.

The emergence of new neighbourhoods

Lamu town comprises three areas in terms of architectural and urban morphology. The Stone Town, object of the UNESCO world heritage designation, is the oldest part of town, and is historically home to the town’s merchant elite. The immediately adjacent neighborhoods of Langoni and Gardeni are former agricultural areas that became popular, less affluent neighborhoods. They were initially built up with wattle-and-daub constructions, which have more recently been replaced with more permanent constructions including modern apartment buildings. The third type of built fabric in Lamu are the new neighborhoods that have emerged on the outskirts, roughly since the 2000s. These areas tend to have homes built on regularized plots, with a size of 30x40 feet. Lamu residents referred to these areas as "bushy" or "forest" before they evolved into well-defined neighbourhoods.

Historically, Stone Town housed the wealthier segments of society, while mud and thatch construction accommodated the less affluent.

These two distinct forms of domestic architecture, however, are interconnected and belong to the same cultural continuum. Lamu residents capture this relationship with the saying "Msitu ni ule ule komba ni wengine," which translates to "the forest is the same, but with different bushes." The differentiation of these two areas has gradually faded away with the replacement of mud by coral blocks.

The notion that stone signifies Arab culture and thatch represents African culture is erroneous, as Lamu's inhabitants have diverse ethnic backgrounds, and construction materials do not correspond to specific racial categories.

Lamu old and new neighborhoods boundary in 2003

Lamu old and new neighborhoods boundary in 2003However, stone houses still symbolise social status and lineage, providing a sense of permanence and privacy within Swahili culture. These stone houses did not arise from an ideal prototype but rather evolved through the amalgamation of materials and practices by various homebuilders over time. They emerged due to the blending and referencing of the existing tradition of using coral stone for the houses of the merchant elite, as art historian Prita Meier has shown.

The same architectural styles persisted in Lamu for centuries in both towns and houses, characterised by a significant contrast between stone and mud constructions. Lifestyle disparities between the stone and mud towns were evident in the character of the main street, with Langoni displaying a higher density of shops that gradually decreased in number but increased in size as one moved closer to the area of Mkomani.

What changes in spatial organisation, if any, have occurred with this growth?

The new areas, with their regular plot sizes of 30x40 feet, feature new house types. At the same time, many factors influencing the organisation of domestic space remained relatively unchanged in Lamu over centuries. The same construction methods, materials, climate, and plot size continued to shape its domestic culture. However, there were significant shifts in women’s expectations, comfort, and need for seclusion and privacy, and these have become more pronounced in recent decades.

Women & domestic culture

Exploring women's perspectives within Lamu’s evolving domestic culture builds upon feminist approaches to architecture and urbanism. These studies displaced the predominantly masculine lens of previous scholarship, which often reproduced patriarchal conceptions of dwelling culture and urban development.

Dwelling undergoes a natural evolution as inhabitants personalise their homes to align with their preferences and actively adapt their living spaces, fostering a sense of accomplishment, self-expression, and autonomy. The concept of home gradually takes on deeper dimensions, intertwining with a profound sense of belonging, cherished memories, and past life encounters. The presence of relationships, residential history, familiarity, and established routines collectively cultivate the comforting feeling of being truly "at home."

Exploring women's perspectives within Lamu’s evolving domestic culture builds upon feminist approaches to architecture and urbanism. These studies displaced the predominantly masculine lens of previous scholarship, which often reproduced patriarchal conceptions of dwelling culture and urban development.

Dwelling undergoes a natural evolution as inhabitants personalise their homes to align with their preferences and actively adapt their living spaces, fostering a sense of accomplishment, self-expression, and autonomy. The concept of home gradually takes on deeper dimensions, intertwining with a profound sense of belonging, cherished memories, and past life encounters. The presence of relationships, residential history, familiarity, and established routines collectively cultivate the comforting feeling of being truly "at home."

Amid the numerous studies investigating various facets of dwelling, this research probes women's roles and practices as both agents of change and guardians of cultural heritage. By actively immersing ourselves in their everyday practices and negotiations with house builders, this study examines the evolution of domestic culture and explores how meanings and values associated with home have evolved over time.

Examining the intricate interplay among architecture, gender roles, and spatial dynamics reveals entrenched biases, the profound impact of gender on social and spatial constructs, and some unexpected consequences of urban development.

Typical Stone house (L), typical Swahili house from Kashmir and Langoni (M), and what so-called modern house from Melimani (R)